The Reason Black History Month Is in February

This makes a lot of sense.

Every February, we celebrate a special holiday. And no, I'm not talking about Valentine's Day. I'm referring to the 28 (or 29) days we dedicate to honoring Black History Month, our nation's way of showing respect and recognition for the hard work of and sacrifices made by African Americans.

"Black History Month shouldn’t be treated as though it is somehow separate from our collective American history, or somehow just boiled down to a compilation of greatest hits from the March on Washington, or from some of our sports heroes," President Barack Obama said in a 2016 speech. "It’s about the lived, shared experience of all African Americans, high and low, famous and obscure, and how those experiences have shaped and challenged and ultimately strengthened America. It’s about taking an unvarnished look at the past so we can create a better future. It’s a reminder of where we as a country have been so that we know where we need to go."

Despite a tragic American history that saw Black people bought and sold into slavery, a continuing fight against everyday racism, and urgent issues like police brutality, we've remained strong. Black Americans confront a layered, painful past while making countless cultural contributions. We've been responsible for classic books, beauty brands (we're looking at you, Madam C.J. Walker), creative small businesses, films, and inventions we can't imagine life without—and we're still completing countless impressive firsts.

But out of all the calendar pages, why is Black History Month in February (a.k.a. the month of love)? And who started this tradition? Here's a primer.

It all started with a man named Carter G. Woodson.

Harvard-educated historian Carter G. Woodson is credited with creating Black History Month. According to Daryl Michael Scott, a history professor at Howard University, Woodson got the idea in 1915 after attending a celebration in Illinois for the 50th anniversary of the 13th Amendment, which under Abraham Lincoln's presidency, abolished slavery in 1863 in the Confederate states that seceded from the U.S.: Mississippi, Florida, South Carolina, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Arkansas, Texas, Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee. It wasn't until two years later on June 19, 1865 that all people held as property in the United States were officially free. (Which is why we celebrate Juneteenth).

The festivities honoring the proclamation lasted for three weeks, with various exhibits depicting events in African American culture. In 1915, after seeing this display, Woodson decided to form what is now named the Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History (ASALH), in order to encourage the study of the accomplishments made by Black Americans.

The Black history celebrations expanded to a week-long event.

According to Scott, after Woodson wrote The Journal of Negro History in 1916, which chronicled the overlooked achievements of African Americans, he sought to amplify Black people's success and spread his findings to a wider audience. Through community outreach, he encouraged his fraternity Omega Psi Phi to promote his work. In 1924, the fraternity responded by creating "Negro Achievement Week."

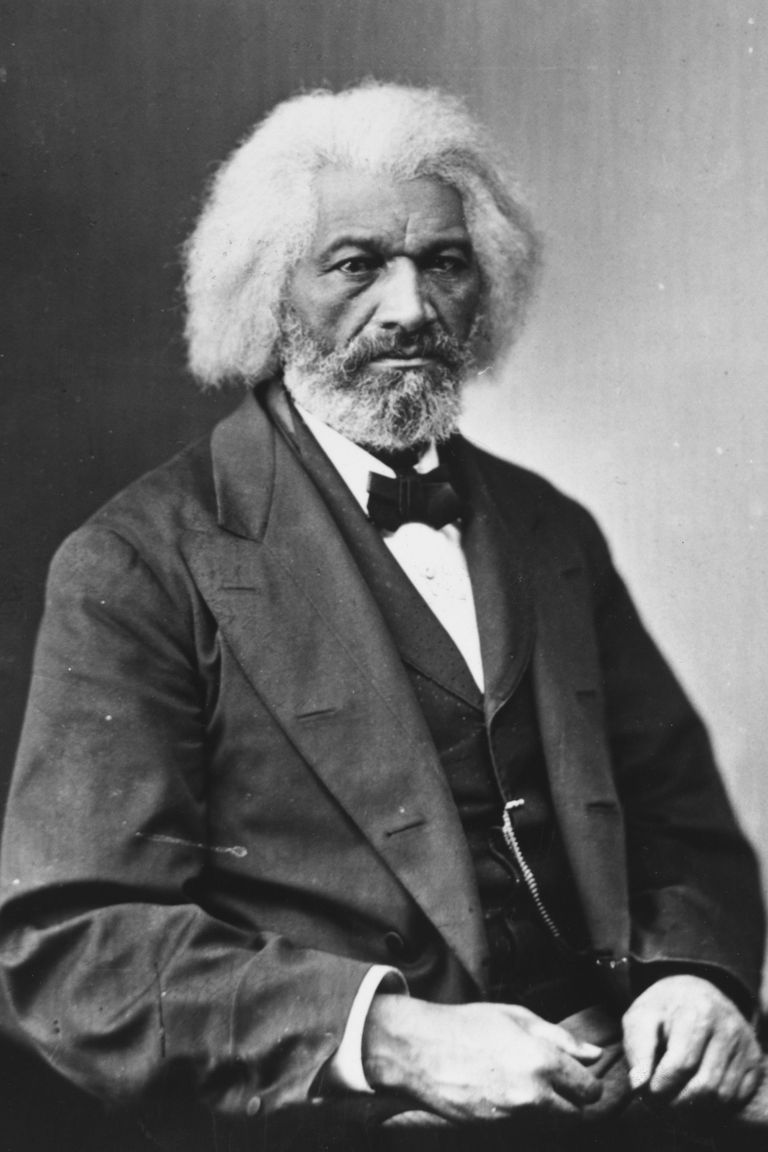

February was selected to align with President Lincoln and Frederick Douglass's birthdays.

Two years later, despite Omega Psi Phi's efforts, Woodson still wanted to make a bigger impact. So in 1926, he and the ASALH officially declared the second week of February to be "Negro History Week," announcing the news through a press release, according to Scott.

"This was celebrated for years and was chosen because of the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln on February 12th, and Frederick Douglass on February 14th," says Zebulon Miletsky, the co-chair of the marketing and PR committee for ASALH.

Both Lincoln and Douglass had long been celebrated by the Black community in the years before "Negro History Week" was created. Since his assassination, Lincoln's birthday was honored by both African Americans and Republicans alike, so the ASALH only solidified this tradition. And Douglass was already revered as a change-making abolitionist and orator whose legacy would now be cemented with festivities that honored the people he fought so hard for.

President Gerald Ford declared Black History Month official.

In the 50 years that followed, according to History.com, clubs, schools, and communities across the country began taking part in the week-long celebration. Slowly, more and more U.S. cities (like New York and Chicago), declared official recognition of "Negro History Week." Particularly in the 1960s, during the civil rights movement, with wider public knowledge of the trials and triumphs of African Americans, a mere seven days turned into a month-long recognition.

"In the 1940s, efforts began slowly within the Black community to expand the study of Black history in the schools. In the South, Black teachers often taught Negro History as a supplement to United States history," Scott says. "During the civil rights movement in the South, the Freedom Schools incorporated Black history into the curriculum to advance social change. The Negro History movement was an intellectual insurgency that was part of every larger effort to transform race relations."

Consequentially, the ASALH expanded the recognition to Black History Month. To solidify this change, in 1976, President Ford declared February "Black History Month" in a commemorative speech. He urged citizens to "seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of Black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history."

Today, Black History Month continues to be widely celebrated.

The observations live on as we take the time to honor greats such as Martin Luther King Jr., James Baldwin, Maya Angelou, and our very own Oprah Winfrey. In the years following Ford's speech, congress passed a law in 1986 that deemed February "National Black (Afro-American) History Month.” Both presidents Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton issued their own proclamations recognizing it as a national observance, and every POTUS has issued one annually since 1996.

But as time goes on, just like Woodson's idea of highlighting people of color went from a single organization to an entire month of recognition, many—like the O of O—feel that again, we need to think bigger when it comes to appreciating Black lives. In fact according to Scott, before his death in 1950, Woodson himself wished to see the acknowledgment of African Americans' past become a regular daily occurrence rather than be relegated to a single month.

"I have a wonderful phrase that Maya Angelou wrote in one of her poems," Oprah said in an Instagram post. "It said 'I come as one, but I stand as 10,000.' I'm doing that right now... I don't reserve it for one month. I believe that Black history is a part of every day, every life, every year, all the time."

Library of Congress

Library of Congress