Guyana

A 60-year schism

The president shuts down parliament

Nov 15th 2014 | From the print edition

WHEN 33 opposition MPs took their seats in Guyana’s National Assembly on November 10th for parliament’s first sitting in since July, they faced a bank of empty chairs. In place of government politicians were copies of a presidential decree that “prorogued” parliament until further notice. Governance was barely working before. The suspension of parliament ends the pretence.

The source of the confrontation is the 2011 election, which produced a split result. Donald Ramotar won the presidency but two parties opposed to him secured a single-seat majority in the National Assembly. President and parliament have bickered ever since. Mr Ramotar suspended the legislature to avoid a no-confidence vote, which looked certain to pass. He will now attempt to govern his fractious country of 750,000 people without recourse to parliament, possibly until the end of April, when he needs a new budget for routine spending to continue.

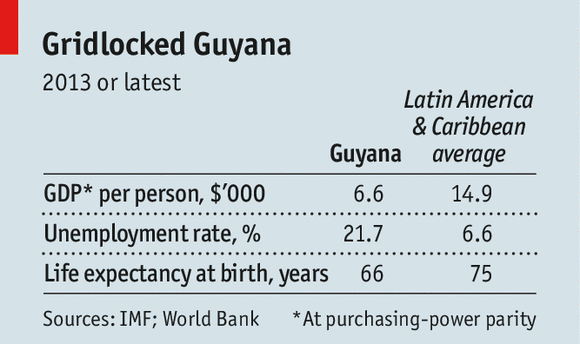

The conflict goes deeper than ordinary political rivalry. It is a big part of the reason that Guyana has remained relatively poor (see chart on previous page). Politics have been polarised by race for 60 years. Most Indo-Guyanese—descendants of indentured labourers who were brought over when the country was a British colony—support Mr Ramotar’s People’s Progressive Party (PPP). Most Afro-Guyanese have backed the People’s National Congress (PNC), now part of the main opposition group, A Partnership For National Unity.

After unrest in the early 1960s, the PNC held power through rigged elections for 28 years. During the 1980s Guyana was briefly nearly as poor as Haiti, the poorest country in the Americas. From the 1990s coalitions led by the PPP formed governments made increasingly complacent by unstinting support from Indo-Guyanese, the largest group of voters.

The co-habitation of the past three years has been no more productive. Mr Ramotar has vetoed opposition-sponsored legislation and refused to call local-government elections—which have not been held since 1994. President and parliament have failed to co-operate on building infrastructure or on enacting needed legislation to fight money laundering.

The immediate prospects are not bright. Without a new budget, which is unlikely to pass, parliament must be dissolved by April, triggering new elections. The likeliest outcome would then be a continuation of divided government or a return to the stultifying rule of the PPP.

But there are hopeful signs. Mixed marriages have produced mixed-race children. Guyana’s indigenous Amerindian population has grown; it is now nearly a tenth of the total. Voters weary of the old politics provide a base for the multi-ethnic Alliance for Change, which took seven of the 65 parliamentary seats in 2011. Some Guyanese want to move beyond stalemate.