AMERICAN TERRORIST: CIA'S BLUE EYED BOY

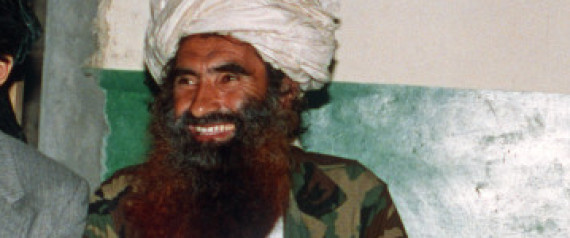

Jalaluddin Haqqani, Once CIA's 'Blue-Eyed Boy,' Now Top Scourge For U.S. In Afghanistan

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/...nistan_n_987762.html

WASHINGTON -- The U.S.'s new public enemy No. 1 in Afghanistan is one of its own making.

Ten years into the occupation of Afghanistan, American officials describe the militia led by Jalaluddin Haqqani as the country's deadliest insurgent group, responsible for a slew of particularly bold attacks, including the day-long assault three weeks ago on the U.S. embassy in Kabul.

But Haqqani's rise to power can be traced directly back to the secret, multi-billion-dollar U.S. campaign to create a radicalized and well-equipped army of Islamic jihadists -- known as the mujahideen -- to lead a war against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan in the 1980s.

Back then, when a top U.S. foreign policy goal was to bog the invading Soviets down in Afghanistan, the ferocious Haqqani was one of the CIA's favorite commanders, showered with money and shoulder-fired missiles and other weapons -- and sent out to repel the foreign occupiers.

"We facilitated his rise -- we and the Saudis and Pakistani intelligence," said Steve Coll, author of "Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan and Bin Laden, From the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001."

"In Afghanistan, what goes around comes around is sort of the lesson of the last 30 years," he said.

Haqqani was admired for being particularly tough and ruthless. "There was a bit of a racist attitude about the Afghans" among the Saudi, Pakistani and U.S. intelligence services, Coll said. Haqqani "was everybody's idea of the noble savage."

Peter Tomsen, a former ambassador to Afghanistan, told PBS Frontline in 2006 that the CIA "gave Haqqani the infrastructure" to build his network.

"It is certainly quite plausible to argue that the group is stronger today than it would have been without the assistance rendered back in the 1980s," said Paul R. Pillar, a former senior CIA analyst who now teaches at Georgetown University.

Haqqani is said to have introduced suicide bombing as a tactic in Afghanistan. But back then, Haqqani's radicalism and profoundly anti-Western views weren't a liability -- they were an asset. Set on making things as difficult for the Soviets as possible, the U.S. was pushing a militant strain of Islam into the traditionally more moderate Afghan culture, by doing such things as spending $51 million to supply Afghan schoolchildren with textbooks filled with violent images and militant Islamic teachings.

But after the Soviets left Afghanistan -- more than 22 years ago now -- so did the CIA. What the Americans left behind was a generation steeped in violence, warlords inflamed with hatred of foreign invaders -- and those schoolbooks, which for years served as the Afghan school system's core curriculum.

Then, on Oct. 7, 2001, the U.S. invaded Afghanistan in response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks; for the last 10 years, it's been the Americans' turn to be the foreign occupiers.

Now, from his base in Pakistan's North Waziristan region, an essentially ungoverned area near the border of Afghanistan, Haqqani leads the "Haqqani network," which The New York Times recently likened to "the Sopranos of the Afghanistan war."

The man who introduced suicide bombings to Afghanistan has made "complex and strategic suicide attacks" against Western targets, like embassies and hotels, the calling card of his network.

Adm. Mike Mullen, the outgoing chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, made headlines three weeks ago when he singled out the Haqqani network in his testimony before a Senate committee and then described the group as "a veritable arm" of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) agency.

Other U.S. officials have since tried to walk back Mullen's comment, but not before it triggered a nationalist backlash in Pakistan and whipped up media fears there of an imminent U.S. invasion.

In remarks to Al Jazeera television, Pakistan's Foreign Minister Hina Rabbani Khar fired back at Mullen. "If we talk about links, I am sure the CIA also has links with many terrorist organizations around the world, by which we mean intelligence links," she said. "And this particular network, that they continue to talk about, is a network which was the blue-eyed boy of the CIA itself for many years. I mean, it was created by the CIA, it could be said."

The charge also led the Pakistani ambassador to the U.S. to delightedly show an Indian television reporter a clip on his cell phone of President Ronald Reagan hosting Haqqani at the White House -- although it later turned out that the picture was not of Haqqani, but of a different mujahideen entirely.

Despite the crucial context it provides for the war that ensued, the history of American intervention in Afghanistan has been largely overlooked -- as it was in media coverage of the 10th anniversary of the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

Paul Fitzgerald and Elizabeth Gould, a journalistic husband-and-wife-team who have reported extensively about Afghanistan, wrote in 2009 about what happened after the CIA left Afghanistan in the late 1980s: "The Afghan people were left to deal with the blowback from the mujahideen fighters who had been supported by the largest publicly known U.S. covert operation since Vietnam. Over the next few years that process would give rise to the Taliban and morph into the threat the U.S. faces today."

U.S. policy there "has been short sighted from the very beginning," Fitzgerald said in an interview. "It's a history of short-sightedness."

The problem is often whom the U.S. picks as its proxies. "I think we have a pretty good track record at picking the worst possible people," Fitzgerald said. "We never pick people who stand for our values."

"Haqqani was one of the instruments that was being used to cause problems for the Soviets in Afghan," Pillar said. "But when the Soviets were gone, both initially from Afghanistan and more broadly with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the equities were changed."

"One can sum that all up by labeling it appropriately as blowback," he added.

"The lesson is: Watch out who your friends are," Coll said. The U.S. "outsourced the politics of the war to the Pakistani ISI and they favored radical Islamist groups with an anti-American agenda. And we accepted that."

The conflict between apparent expediency on the one side and American values on the other remains vivid in current policies, he noted. Even now, Coll said, the U.S. has "empowered a lot of warlords in the country who do not share our values."

"We declare that our goal is to establish rule of law and civil society and peace," he said, "and then we work through local warlords who are not accountable to anyone and who basically control their territory by the gun."

Similarly, John Hanrahan recently wrote for the Nieman Foundation for Journalism that "we should learn the 'blowback' lessons from those earlier days and bear in mind that our actions there today -- night raids, attacks, support for a corrupt government, internment without charges of a couple thousand Afghans in Bagram prison, etc. -- can again produce negative future consequences for both the beleaguered Afghan people and the United States." (Disclosure: I also work for the Nieman Foundation.)

Meanwhile, a growing list of U.S. senators is heeding Mullen's advice and pushing to designate the Haqqani network as a terrorist organization. But that move, ironically, itself might backfire, because that designation would prevent Haqqani from ever being part of a peace process.

And as Pakistani scholar Saifullah Mahsud told the Economist last week, to their supporters, the Haqqanis are fighting an occupying force, just as they did the Soviets before.

.

Jalaluddin Haqqani, Once CIA's 'Blue-Eyed Boy,' Now Top Scourge For U.S. In Afghanistan

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/...nistan_n_987762.html

WASHINGTON -- The U.S.'s new public enemy No. 1 in Afghanistan is one of its own making.

Ten years into the occupation of Afghanistan, American officials describe the militia led by Jalaluddin Haqqani as the country's deadliest insurgent group, responsible for a slew of particularly bold attacks, including the day-long assault three weeks ago on the U.S. embassy in Kabul.

But Haqqani's rise to power can be traced directly back to the secret, multi-billion-dollar U.S. campaign to create a radicalized and well-equipped army of Islamic jihadists -- known as the mujahideen -- to lead a war against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan in the 1980s.

Back then, when a top U.S. foreign policy goal was to bog the invading Soviets down in Afghanistan, the ferocious Haqqani was one of the CIA's favorite commanders, showered with money and shoulder-fired missiles and other weapons -- and sent out to repel the foreign occupiers.

"We facilitated his rise -- we and the Saudis and Pakistani intelligence," said Steve Coll, author of "Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan and Bin Laden, From the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001."

"In Afghanistan, what goes around comes around is sort of the lesson of the last 30 years," he said.

Haqqani was admired for being particularly tough and ruthless. "There was a bit of a racist attitude about the Afghans" among the Saudi, Pakistani and U.S. intelligence services, Coll said. Haqqani "was everybody's idea of the noble savage."

Peter Tomsen, a former ambassador to Afghanistan, told PBS Frontline in 2006 that the CIA "gave Haqqani the infrastructure" to build his network.

"It is certainly quite plausible to argue that the group is stronger today than it would have been without the assistance rendered back in the 1980s," said Paul R. Pillar, a former senior CIA analyst who now teaches at Georgetown University.

Haqqani is said to have introduced suicide bombing as a tactic in Afghanistan. But back then, Haqqani's radicalism and profoundly anti-Western views weren't a liability -- they were an asset. Set on making things as difficult for the Soviets as possible, the U.S. was pushing a militant strain of Islam into the traditionally more moderate Afghan culture, by doing such things as spending $51 million to supply Afghan schoolchildren with textbooks filled with violent images and militant Islamic teachings.

But after the Soviets left Afghanistan -- more than 22 years ago now -- so did the CIA. What the Americans left behind was a generation steeped in violence, warlords inflamed with hatred of foreign invaders -- and those schoolbooks, which for years served as the Afghan school system's core curriculum.

Then, on Oct. 7, 2001, the U.S. invaded Afghanistan in response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks; for the last 10 years, it's been the Americans' turn to be the foreign occupiers.

Now, from his base in Pakistan's North Waziristan region, an essentially ungoverned area near the border of Afghanistan, Haqqani leads the "Haqqani network," which The New York Times recently likened to "the Sopranos of the Afghanistan war."

The man who introduced suicide bombings to Afghanistan has made "complex and strategic suicide attacks" against Western targets, like embassies and hotels, the calling card of his network.

Adm. Mike Mullen, the outgoing chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, made headlines three weeks ago when he singled out the Haqqani network in his testimony before a Senate committee and then described the group as "a veritable arm" of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) agency.

Other U.S. officials have since tried to walk back Mullen's comment, but not before it triggered a nationalist backlash in Pakistan and whipped up media fears there of an imminent U.S. invasion.

In remarks to Al Jazeera television, Pakistan's Foreign Minister Hina Rabbani Khar fired back at Mullen. "If we talk about links, I am sure the CIA also has links with many terrorist organizations around the world, by which we mean intelligence links," she said. "And this particular network, that they continue to talk about, is a network which was the blue-eyed boy of the CIA itself for many years. I mean, it was created by the CIA, it could be said."

The charge also led the Pakistani ambassador to the U.S. to delightedly show an Indian television reporter a clip on his cell phone of President Ronald Reagan hosting Haqqani at the White House -- although it later turned out that the picture was not of Haqqani, but of a different mujahideen entirely.

Despite the crucial context it provides for the war that ensued, the history of American intervention in Afghanistan has been largely overlooked -- as it was in media coverage of the 10th anniversary of the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

Paul Fitzgerald and Elizabeth Gould, a journalistic husband-and-wife-team who have reported extensively about Afghanistan, wrote in 2009 about what happened after the CIA left Afghanistan in the late 1980s: "The Afghan people were left to deal with the blowback from the mujahideen fighters who had been supported by the largest publicly known U.S. covert operation since Vietnam. Over the next few years that process would give rise to the Taliban and morph into the threat the U.S. faces today."

U.S. policy there "has been short sighted from the very beginning," Fitzgerald said in an interview. "It's a history of short-sightedness."

The problem is often whom the U.S. picks as its proxies. "I think we have a pretty good track record at picking the worst possible people," Fitzgerald said. "We never pick people who stand for our values."

"Haqqani was one of the instruments that was being used to cause problems for the Soviets in Afghan," Pillar said. "But when the Soviets were gone, both initially from Afghanistan and more broadly with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the equities were changed."

"One can sum that all up by labeling it appropriately as blowback," he added.

"The lesson is: Watch out who your friends are," Coll said. The U.S. "outsourced the politics of the war to the Pakistani ISI and they favored radical Islamist groups with an anti-American agenda. And we accepted that."

The conflict between apparent expediency on the one side and American values on the other remains vivid in current policies, he noted. Even now, Coll said, the U.S. has "empowered a lot of warlords in the country who do not share our values."

"We declare that our goal is to establish rule of law and civil society and peace," he said, "and then we work through local warlords who are not accountable to anyone and who basically control their territory by the gun."

Similarly, John Hanrahan recently wrote for the Nieman Foundation for Journalism that "we should learn the 'blowback' lessons from those earlier days and bear in mind that our actions there today -- night raids, attacks, support for a corrupt government, internment without charges of a couple thousand Afghans in Bagram prison, etc. -- can again produce negative future consequences for both the beleaguered Afghan people and the United States." (Disclosure: I also work for the Nieman Foundation.)

Meanwhile, a growing list of U.S. senators is heeding Mullen's advice and pushing to designate the Haqqani network as a terrorist organization. But that move, ironically, itself might backfire, because that designation would prevent Haqqani from ever being part of a peace process.

And as Pakistani scholar Saifullah Mahsud told the Economist last week, to their supporters, the Haqqanis are fighting an occupying force, just as they did the Soviets before.

.