Another pope’s apology isn’t enough when Catholic Church’s cover-ups and hypocrisy continue to this day

As Francis visits Canada, we need to ask: have churches and governments created conditions allowing clergy to continue their sexual abuse of children?

Sun., July 24, 2022timer6 min. read -- Source -- https://www.thestar.com/opinio...nue-to-this-day.html

The truth is, there have been many apologies issued by many popes.

But as Pope Francis’s visit to Canada begins this weekend, the question to be asked is whether these men have taken substantive actions to end the abuse in which the church they lead has been complicit.

The Catholic Church and its officials have directed, authorized, counselled and/or were complicit in the horrific physical and sexual abuse of children; subjugation, vilification and violence against women; and the deaths of millions of Indigenous peoples in Canada, the United States, Australia, New Zealand, South America and the African continent. According to recent inquiries, that abuse has continued into the present.

For some First Nation, Inuit and Métis survivors, this papal visit to Canada that begins this weekend in Alberta is an important part of their healing journey. For others, the Pope is the last person they want on their territories, as he represents a religious organization that has caused much misery around the world.

In 2017, Australia’s Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sex Abuse found that from 1950 into the 1980s, 4,445 victims were sexually abused in a Catholic setting, but not all victims were recorded before 1950. It found that the cover-up of sexual abuse committed by Catholic priests and brothers was systemic — a matter of church policy — and abusers were neither reported to the police nor expelled.

Last year, an independent inquiry concluded that there have been more than 216,000 victims of sexual abuse by French Catholic clergy between 1950 and 2020. The church was found to have turned a blind eye to the abuse perpetrated by 3,000 priests and other people involved in the church. The evidence showed that the church was more concerned about protecting its image than preventing the abuse from continuing. Like the situation in Australia, the church did not hold abusers to account. To make matters worse, in some countries, those sexual predators have been left to continue the abuse.

An investigation by The Associated Press in 2019 found that nearly 1,700 priests and other clergy members that the Roman Catholic Church itself considers “credibly accused of child sexual abuse” live under the radar with easy access to children. The investigation revealed that these men are employed as teachers, counsellors, juvenile detention officers, nurses and foster parents, or work in family shelters and even Disney World — roles that keep them disturbingly close to children.

They easily pass fingerprint tests and/or criminal record checks (since they were never prosecuted); not surprisingly, a large number have gone on to commit additional sexual assaults. The fact that the church never held them to account for child sexual abuse is bad enough, but the subsequent cover-up and failure to monitor them now has put countless American children at risk.

The question needs to be asked here in Canada: have churches and governments created the conditions allowing Catholic clergy to continue their sexual abuse of children?

In 2016, the federal government spent over $1.5 million to hire 17 private investigators to identify those believed to have committed sexual abuse at residential schools. More than 5,300 perpetrators were identified, but not for the purposes of criminal prosecution. Instead, they were invited to participate in the hearings related to compensation, but not surprisingly, the vast majority did not accept the invitation.

Of the more than 5,000 sexual predators who abused the majority of 150,000 First Nations, Inuit and Métis children in residential schools, a mere fraction have ever faced criminal charges. Fewer than 50 have been convicted; and of those, most spent only months in prison. It begs the question: where are they now — and how many more children have they abused because neither the churches nor law enforcement saw fit to protect children from known sex offenders?

The pomp and circumstance surrounding the Pope’s visit has overshadowed these important questions.

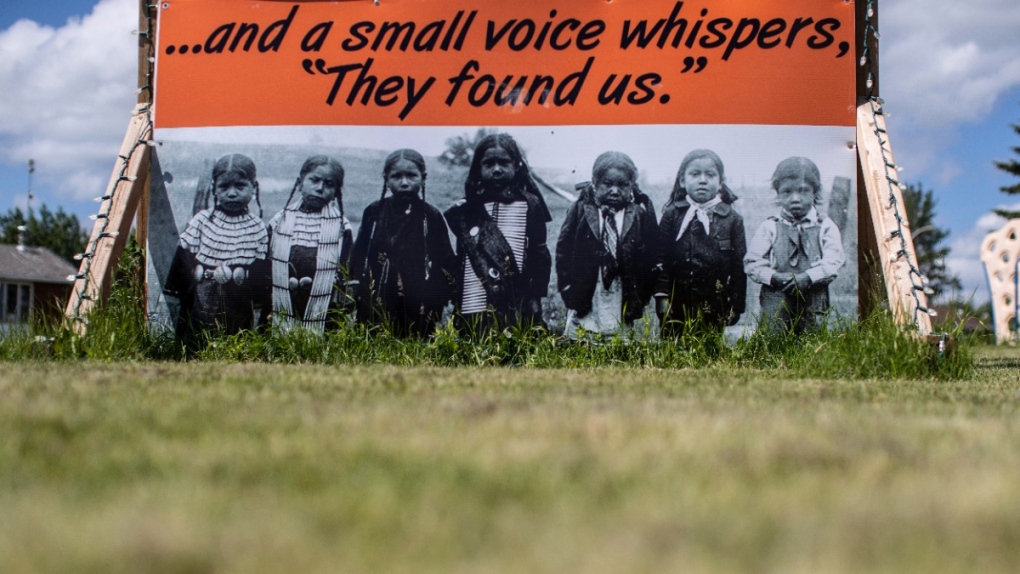

It would be wrong to assume that the legacy of Indian residential schools is about historic or past abuses. There were many horrific abuses in those schools, from medical experimentation and torture to severe beatings and deaths. The many unmarked graves being identified across the country are evidence that the extent of the crimes is far worse than has been reported.

The failure to hold the perpetrators to account — then and now — created an opportunity for the abuse to continue into the present, just as it has in other countries. While not all survivors want criminal prosecutions, some do. But the passage of time permitted by the church and government will have clearly prejudiced their cases. Had Canada created a special prosecution team when they first knew about the abuses, things may have been different — but maybe not, given the change of tactics by the church in other parts of the world.

Churches can now be covered by “church abuse and molestation” liability insurance, which means that any litigation or claims against the church for abuse may well have to face a team of aggressive insurance lawyers. In some areas, the Catholic Church has adopted more aggressive litigation tactics like hiring private detectives to dig up dirt on claimants; engaging large, powerful law firms; fighting to keep documents secret; and/or filing countersuits against parents.

In one case, the Diocese of Honolulu countersued a mother, claiming she failed to protect her children from abusive priests. These actions are clearly meant to dissuade others from bringing forward criminal or civil cases. One Roman Catholic cardinal called out the church for concealing, manipulating and/or destroying documents in an effort to cover up sexual abuse.

In addition to the Catholic Church not sharing all documents related to Indian residential schools in Canada, the federal government destroyed 15 tons of paper documents related to the residential school system between 1936 and 1944. St. Anne’s residential school survivors are still battling Canada in court for the release of documents that detail the abuse they suffered in Fort Albany, Ont.

All of these actions — from hiding documents to failing to prosecute sex offenders — betray government- and church-stated commitments to reconciliation. If either institution wants to engage in substantive reconciliation, it must listen to the survivors, the families and community leaders who have made demands that go beyond carefully worded apologies. There have been many diverse Indigenous voices calling for substantive action in addition to an apology. I believe that all of these actions should be implemented, including, but not limited to the following:

- Government and the Catholic Church must take whatever means necessary to stop ongoing sexual abuse of children and take urgent steps to prevent it in the future;

- Governments and the church must hold known sexual predators to account;

- Governments and the church must contribute whatever funding is necessary to identify the children in unmarked graves across Canada, and support communities to bring them home and/or memorialize them;

- All documents related to any aspect of Indian residential schools, day schools and other church activities impacting Indigenous peoples must be released by governments and the church;

- Stop fighting St. Anne’s residential school survivors in court;

- The church must finally pay its agreed-upon compensation and any additional compensation needed to make full reparations for its crimes and cover-ups related to Indigenous peoples;

- All 94 Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to be implemented without further delay;

- Return lands held by the Catholic Church back to First Nations who desire their return;

- Immediately rescind, repeal or withdraw the Doctrine of Discovery (by whatever legal means necessary to give it effect);

- Canada should appoint a special prosecutor to bring sexual offenders to justice in a way that does not retraumatize survivors, families and communities;

- There should be an independent review of the actions of the church in relation to sexual abuse in Indian residential schools; and

- Ensure that known abusers are listed and not permitted to work near children.

Understanding that survivors will each have their own vision of reconciliation, for many, anything less than an apology that includes an unqualified admission of the crimes committed, a full acceptance of responsibility, and a commitment to end the abuse and make full reparations will be just another empty apology and continuing injustice for First Nations, Inuit and Métis.

The Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line is available 24 hours a day for anyone experiencing pain or distress as a result of a residential school experience. Support is available at 1-866-925-4419.

:format(webp)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/XJNILFJKI5C4JNJMRZDWDHVN24.jpg)

:format(webp)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/KV3VNC4HOBO6LGH2G5QEHHLEHY.JPG)

:format(webp)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/LDBXJRUWJZBMRERYDS6PBVYAQ4.JPG)

:format(webp)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/TZKHOXYFWVFRTIGZTIA7DLQLF4.jpg)

:format(webp)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/4VTOJ33EAZCHJDDAQ6Y7FYYZ7U.jpg)

:format(webp)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/BXT2INTQ7JGSNMBLHINE5IXIWI.jpg)

:format(webp)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/K3DELDEO5FEHTKUYRAM64756PI.jpg)