CHARLES I

Charles I

Charles I

- Born:

- November 19, 1600 Scotland

- Title / Office:

- king (1625-1649), Scotland king (1625-1649), England king (1625-1649), Ireland

- Political Affiliation:

- Cavalier

- House / Dynasty:

- House of Stuart

Charles I, (born November 19, 1600, Dunfermline Palace, Fife, Scotland—died January 30, 1649, London, England), king of Great Britain and Ireland (1625–49), whose authoritarian rule and quarrels with Parliament provoked a civil war that led to his execution.

Charles was the second surviving son of James VI of Scotland and Anne of Denmark. He was a sickly child, and, when his father became king of England in March 1603 (see James I), he was temporarily left behind in Scotland because of the risks of the journey. Devoted to his elder brother, Henry, and to his sister, Elizabeth, he became lonely when Henry died (1612) and his sister left England in 1613 to marry Frederick V, elector of the Rhine Palatinate.

All his life Charles had a Scots accent and a slight stammer. Small in stature, he was less dignified than his portraits by the Flemish painter Sir Anthony Van Dyck suggest. He was always shy and struck observers as being silent and reserved. His excellent temper, courteous manners, and lack of vices impressed all those who met him, but he lacked the common touch, travelled about little, and never mixed with ordinary people. A patron of the arts (notably of painting and tapestry; he brought both Van Dyck and another famous Flemish painter, Peter Paul Rubens, to England), he was, like all the Stuarts, also a lover of horses and hunting. He was sincerely religious, and the character of the court became less coarse as soon as he became king. From his father he acquired a stubborn belief that kings are intended by God to rule, and his earliest surviving letters reveal a distrust of the unruly House of Commons with which he proved incapable of coming to terms. Lacking flexibility or imagination, he was unable to understand that those political deceits that he always practiced in increasingly vain attempts to uphold his authority eventually impugned his honour and damaged his credit.

In 1623, before succeeding to the throne, Charles, accompanied by the duke of Buckingham, King James I’s favourite, made an incognito visit to Spain in order to conclude a marriage treaty with the daughter of King Philip III. When the mission failed, largely because of Buckingham’s arrogance and the Spanish court’s insistence that Charles become a Roman Catholic, he joined Buckingham in pressing his father for war against Spain. In the meantime a marriage treaty was arranged on his behalf with Henrietta Maria, sister of the French king, Louis XIII.

Conflict with Parliament

In March 1625, Charles I became king and married Henrietta Maria soon afterward. When his first Parliament met in June, trouble immediately arose because of the general distrust of Buckingham, who had retained his ascendancy over the new king. The Spanish war was proving a failure and Charles offered Parliament no explanations of his foreign policy or its costs. Moreover, the Puritans, who advocated extemporaneous prayer and preaching in the Church of England, predominated in the House of Commons, whereas the sympathies of the king were with what came to be known as the High Church Party, which stressed the value of the prayer book and the maintenance of ritual. Thus antagonism soon arose between the new king and the Commons, and Parliament refused to vote him the right to levy tonnage and poundage (customs duties) except on conditions that increased its powers, though this right had been granted to previous monarchs for life.

The second Parliament of the reign, meeting in February 1626, proved even more critical of the king’s government, though some of the former leaders of the Commons were kept away because Charles had ingeniously appointed them sheriffs in their counties. The failure of a naval expedition against the Spanish port of Cádiz in the previous autumn was blamed on Buckingham and the Commons tried to impeach him for treason. To prevent this, Charles dissolved Parliament in June. Largely through the incompetence of Buckingham, the country now became involved in a war with France as well as with Spain and, in desperate need of funds, the king imposed a forced loan, which his judges declared illegal. He dismissed the chief justice and ordered the arrest of more than 70 knights and gentlemen who refused to contribute. His high-handed actions added to the sense of grievance that was widely discussed in the next Parliament.

By the time Charles’s third Parliament met (March 1628), Buckingham’s expedition to aid the French Protestants at La Rochelle had been decisively repelled and the king’s government was thoroughly discredited. The House of Commons at once passed resolutions condemning arbitrary taxation and arbitrary imprisonment and then set out its complaints in the Petition of Right, which sought recognition of four principles—no taxes without consent of Parliament; no imprisonment without cause; no quartering of soldiers on subjects; no martial law in peacetime. The king, despite his efforts to avoid approving this petition, was compelled to give his formal consent. By the time the fourth Parliament met in January 1629, Buckingham had been assassinated. The House of Commons now objected both to what it called the revival of “popish practices” in the churches and to the levying of tonnage and poundage by the king’s officers without its consent. The king ordered the adjournment of Parliament on March 2, 1629, but before that the speaker was held down in his chair and three resolutions were passed condemning the king’s conduct. Charles realized that such behaviour was revolutionary. For the next 11 years he ruled his kingdom without calling a Parliament.

In order that he might no longer be dependent upon parliamentary grants, he now made peace with both France and Spain, for, although the royal debt amounted to more than £1,000,000, the proceeds of the customs duties at a time of expanding trade and the exaction of traditional crown dues combined to produce a revenue that was just adequate in time of peace. The king also tried to economize in the expenditure of his household. To pay for the Royal Navy, so-called ship money was levied, first in 1634 on ports and later on inland towns as well. The demands for ship money aroused obstinate and widespread resistance by 1638, even though a majority of the judges of the court of Exchequer found in a test case that the levy was legal.

These in fact were the happiest years of Charles’s life. At first he and Henrietta Maria had not been happy, and in July 1626 he peremptorily ordered all of her French entourage to quit Whitehall. After the death of Buckingham, however, he fell in love with his wife and came to value her counsel. Though the king regarded himself as responsible for his actions—not to his people or Parliament but to God alone according to the doctrine of the divine right of kings—he recognized his duty to his subjects as “an indulgent nursing father.” If he was often indolent, he exhibited spasmodic bursts of energy, principally in ordering administrative reforms, although little impression was made upon the elaborate network of private interests in the armed services and at court. On the whole, the kingdom seems to have enjoyed some degree of prosperity until 1639, when Charles became involved in a war against the Scots.

The early Stuarts neglected Scotland. At the beginning of his reign Charles alienated the Scottish nobility by an act of revocation whereby lands claimed by the crown or the church were subject to forfeiture. His decision in 1637 to impose upon his northern kingdom a new liturgy, based on the English Book of Common Prayer, although approved by the Scottish bishops, met with concerted resistance. When many Scots signed a national covenant to defend their Presbyterian religion, the king decided to enforce his ecclesiastical policy with the sword. He was outmanoeuvred by a well-organized Scottish covenanting army, and by the time he reached York in March 1639 the first of the so-called Bishops’ Wars was already lost. A truce was signed at Berwick-upon-Tweed on June 18.

On the advice of the two men who had replaced Buckingham as the closest advisers of the king—William Laud, archbishop of Canterbury, and the earl of Strafford, his able lord deputy in Ireland—Charles summoned a Parliament that met in April 1640—later known as the Short Parliament—in order to raise money for the war against Scotland. The House insisted first on discussing grievances against the government and showed itself opposed to a renewal of the war; so, on May 5, the king dissolved Parliament again. The collection of ship money was continued and so was the war. A Scottish army crossed the border in August and the king’s troops panicked before a cannonade at Newburn. Charles, deeply perturbed at his second defeat, convened a council of peers on whose advice he summoned another Parliament, the Long Parliament, which met at Westminster in November 1640.

The new House of Commons, proving to be just as uncooperative as the last, condemned Charles’s recent actions and made preparations to impeach Strafford and other ministers for treason. The king adopted a conciliatory attitude—he agreed to the Triennial Act that ensured the meeting of Parliament once every three years—but expressed his resolve to save Strafford, to whom he promised protection. He was unsuccessful even in this, however. Strafford was beheaded on May 12, 1641.

Charles was forced to agree to a measure whereby the existing Parliament could not be dissolved without its own consent. He also accepted bills declaring ship money and other arbitrary fiscal measures illegal, and in general condemning his methods of government during the previous 11 years. But while making these concessions, he visited Scotland in August to try to enlist anti-parliamentary support there. He agreed to the full establishment of Presbyterianism in his northern kingdom and allowed the Scottish estates to nominate royal officials.

Meanwhile, Parliament reassembled in London after a recess, and, on November 22, 1641, the Commons passed by 159 to 148 votes the Grand Remonstrance to the king, setting out all that had gone wrong since his accession. At the same time news of a rebellion in Ireland had reached Westminster. Leaders of the Commons, fearing that if any army were raised to repress the Irish rebellion it might be used against them, planned to gain control of the army by forcing the king to agree to a militia bill. When asked to surrender his command of the army, Charles exclaimed “By God, not for an hour.” Now fearing an impeachment of his Catholic queen, he prepared to take desperate action. He ordered the arrest of one member of the House of Lords and five of the Commons for treason and went with about 400 men to enforce the order himself. The accused members escaped, however, and hid in the city. After this rebuff the king left London on January 10, this time for the north of England. The queen went to Holland in February to raise funds for her husband by pawning the crown jewels.

A lull followed, during which both Royalists and Parliamentarians enlisted troops and collected arms, although Charles had not completely given up hopes of peace. After a vain attempt to secure the arsenal at Hull, in April the king settled in York, where he ordered the courts of justice to assemble and where royalist members of both houses gradually joined him. In June the majority of the members remaining in London sent the king the Nineteen Propositions, which included demands that no ministers should be appointed without parliamentary approval, that the army should be put under parliamentary control, and that Parliament should decide about the future of the church. Charles realized that these proposals were an ultimatum; yet he returned a careful answer in which he gave recognition to the idea that his was a “mixed government” and not an autocracy. But in July both sides were urgently making ready for war. The king formally raised the royal standard at Nottingham on August 22 and sporadic fighting soon broke out all over the kingdom.

Civil War of Charles I

In September 1642 the earl of Essex, in command of the Parliamentarian forces, left London for the midlands, while Charles moved his headquarters to Shrewsbury to recruit and train an army on the Welsh marches. During a drawn battle fought at Edgehill near Warwick on October 23, the king addressed his troops in these words: “Your king is both your cause, your quarrel, and your captain. The foe is in sight. The best encouragement I can give you is that, come life or death, your king will bear you company, and ever keep this field, this place, and this day’s service in his grateful remembrance.” Charles I was a brave man but no general, and he was deeply perturbed by the slaughter on the battlefield.

In 1643 the royal cause prospered, particularly in Yorkshire and the southwest. At Oxford, where Charles had moved his court and military headquarters, he dwelt pleasantly enough in Christ Church College. The queen, having sold some of her jewels and bought a shipload of arms from Holland, landed in Yorkshire in February and joined her husband in Oxford in mid-July. Both by letters and by personal appeal she roused him to action and warned him against indecision; “delays have always ruined you,” she observed. The king seems to have assented to a scheme for a three-pronged attack on London—from the west, from Oxford, and from Yorkshire—but neither the westerners nor the Yorkshiremen were anxious to leave their own districts.

In the course of 1643 a peace party of the Parliamentarian side made some approaches to Charles in Oxford, but these failed and the Parliamentarians concluded an alliance with the Scottish covenanters. The entry of a Scottish army into England in January 1644 thrust the king’s armies upon the defensive and the plan for a converging movement on London was abandoned. Charles successfully held his inner lines at Oxford and throughout the west and southwest of England, while he dispatched his nephew, Prince Rupert, on cavalry raids elsewhere. For about a year the king’s forces had the upper hand; yet eventually he put out a number of peace feelers. These came to nothing, but he was cheered by reports that his opponents were beginning to quarrel among themselves.

The year 1645 proved to be one of decision. Charles may have had some foreboding of what was to come, for in the spring he sent his eldest son, Charles, into the west, whence he escaped to France and rejoined his mother, who had arrived there the previous year. On June 14 the highly disciplined and professionally led New Model Army organized and commanded by Sir Thomas Fairfax with Oliver Cromwell as his second in command, defeated the king and Prince Rupert at the Battle of Naseby. This was the first of a long row of defeats the king’s forces suffered through the summer and fall. Charles returned to Oxford on November 5, and by the spring of 1646 Oxford was surrounded. Charles left the city in disguise with two companions late in April and arrived at the camp of the Scottish covenanters at Newark on May 5. But when the covenanters came to terms with the victorious English Parliament in January 1647, they left for home, handing over Charles I to parliamentary commissioners. He was held in Northamptonshire, where he lived a placid, healthy existence and, learning of the quarrels between the New Model Army and Parliament, hoped to come to a treaty with one or the other and regain his power. In June, however, a junior officer with a force of some 500 men seized the king and carried him away to the army headquarters at Newmarket.

After the army marched on London in August, the king was moved to Hampton Court, where he was reunited with two of his children, Henry and Elizabeth. He escaped on November 11, but his friends’ plans to take him to Jersey and thence to France went astray and instead Charles found himself in the Isle of Wight, where the governor was loyal to Parliament and kept him under surveillance at Carisbrooke Castle. There Charles conducted complicated negotiations with the army leaders, with the English Parliament, and with the Scots; he did not scruple to promise one thing to one side and the opposite to the other. He came to a secret understanding with the Scots on December 26, 1647, whereby the Scots offered to support the king’s restoration to power in return for his acceptance of Presbyterianism in Scotland and its establishment in England for three years. Charles then twice refused the terms offered by the English Parliament and was put under closer guard, from which he vainly tried again to escape.

In August 1648 the last of Charles’s Scottish supporters were defeated at the Battle of Preston and the second Civil War ended. The army now began to demand that the king should be put on trial for treason as “the grand author of our troubles” and the cause of bloodshed. He was removed to Hurst Castle in Hampshire at the end of 1648 and thence taken to Windsor Castle for Christmas. On January 20, 1649, he was brought before a specially constituted high court of justice in Westminster Hall.

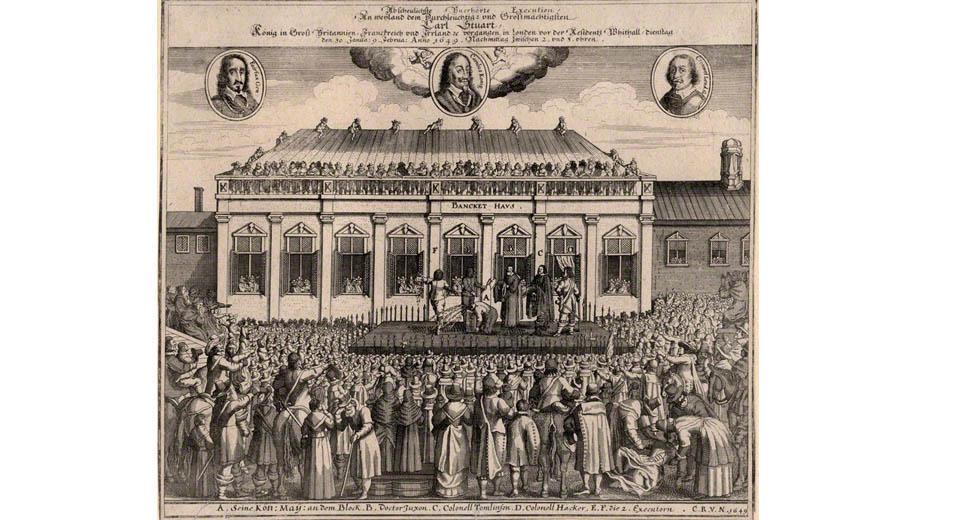

Execution of the king

Charles I was charged with high treason and “other high crimes against the realm of England.” He at once refused to recognize the legality of the court because “a king cannot be tried by any superior jurisdiction on earth.” He therefore refused to plead but maintained that he stood for “the liberty of the people of England.” The sentence of death was read on January 27; his execution was ordered as a tyrant, traitor, murderer, and public enemy. The sentence was carried out on a scaffold erected outside the banqueting hall of Whitehall on the morning of Tuesday, January 30, 1649. The king went bravely to his death, still claiming that he was “a martyr for the people.” A week later he was buried at Windsor.