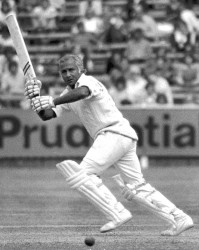

Rohan Kanhai: Indo-Guyanese Hero Turns 80

By Clem Seecharran

Rohan Bholalall Kanhai will be 80 on 26 December 2015. He was born at Port Mourant, British Guiana (Guyana). He represented the West Indies in 79 Tests between 1957 and 1974, captaining them in his last thirteen. He scored 6,227 runs at an average of 47.53, including 15 centuries and 28 half-centuries. His highest score is 256, at Calcutta in December 1958. He appeared in 61

consecutive Tests between 30 May 1957 and 20 February 1969, when a nagging knee injury forced him to withdraw from the tour of New Zealand. In his first-class career (1955-81), he scored 29,250 runs at an average of 49.40, with 86 centuries and 120 half-centuries. He took 325 catches. But it is the way Rohan scored his runs, the unconquerable flair that has stayed with aging devotees. As he explains in his autobiography of 1966, Blasting for Runs: ‘When I bat my whole make-up urges me to destroy the opposition as quickly as possible and once you are on top to never let up…Once I’ve got the fielders with their tongues hanging out I aim to run them into the ground’.

For Indo-Guyanese, the mastery and international recognition of Rohan Kanhai became central to their identity, fortifying their self-esteem even as their political fortunes slumped from the mid-60s. His perceived genius would be refracted through the political, necessarily an ethnic Guyanese prism. Two men from Plantation Port Mourant – Kanhai and Cheddi Jagan (1918-97), the Marxist Indian political leader – possessed the Indo-Guyanese psyche, pivotal to their self-belief at the end of Empire. Cricket was more than politics by other means for Indo-Guyanese. Kanhai and Jagan were intertwined with Indian religious iconography that bordered on deification. It was Rohan’s bravado that made him the quintessential rebel, an instrument of their resolve as descendants of indentured labourers to erase the ‘coolie’ stain. It paralleled Cheddi Jagan’s radicalism, which sprang from similar promptings, and therefore could also be appropriated in the shaping of Indo-Guyanese identity.

The people of Port Mourant, in a breezy, less malarial district, were healthier and imaginative; this engendered strategies of mobility beyond the plantation. It fed their abiding iconoclasm, as well as their meteoric rise. Reform on the plantation (by the ‘Booker’ leader, Jock Campbell) fed the rebellious spirit with an insatiable appetite for change. And with the suspension of the constitution, six months after Cheddi Jagan’s victory at the 1953 general elections, a robust and implacably assertive posture took shape at Port Mourant – the spiritual home of Jaganism. Overseas reporters turned up continually at Port Mourant in the mid-1950s: ‘Little Moscow’. To the people on the plantation, moreover, this spoke of their heroic challenge of the old order, something exhilaratingly provocative that would change their world. This was the spirit of place and temper of the time that fashioned the temperament of Rohan Kanhai.

In the inter-colonial final (against Barbados in 1956), British Guiana made 581: Kanhai 195 (run out). Barbados were dismissed for 211. His skills and his mercurial approach were congruent with a seminal Indo-Guyanese aspiration – to produce a first-rate batsman imbued with passion and panache, in the West Indian style. Kanhai would henceforth speak for his people whether he liked it or not. So when he was selected to tour England with the West Indies in 1957, aged 21 (the youngest member), a long-held dream was answered. The Trinidadian journalist, Owen Mathurin, noted: ‘Kanhai is reputed to have the eyes of an eagle…a first-class bat in the making. He possesses a variety of strokes [and] is very smart in the field…The steep upward trend which British Guiana cricket has taken recently in relation to the other West Indian colonies is due largely to the efforts of this fine young player’.

But West Indies were vanquished 3-0 – a catastrophic fall after their glory of 1950. Kanhai had an undistinguished tour. The pain of Indo-Guyanese was palpable, however credible the explanation for Kanhai’s failure in England. No batsman reached 40 in the averages: Collie Smith was first with 39.60, then came Worrell, 38.88, Sobers, 32.00, Walcott, 27.44; Kanhai was fifth with 22.88, followed by Weekes, 19.50. That Indo-Guyanese were not overwhelmed with despair was largely attributable to Cheddi’s Jagan victory in the general elections of August 1957. All the great stars were eclipsed on that tour of 1957, yet the fear that Rohan may not get another chance was gnawing. Many Indo-Guyanese offered prayers that Rohan Kanhai, like Cheddi Jagan, would deliver soon. Kanhai’s batting in 1958, against Pakistan, built on the possibilities evinced spasmodically in England the previous year. He reached 96 in Trinidad and 62 at home in British Guiana, but his average of 37.37 paled against the Olympian batting of Garry Sobers, who averaged 137.33. But Rohan was selected to go on the West Indies tour of India, in 1958-9. It was seen as a kind of homecoming; and he had to come good now. To do otherwise would give the impression, in Mother India, that the years had been squandered. Two other Port Mourant batsmen were also selected: Basil Butcher and Joe Solomon. Three Indians were in the West Indies team: Kanhai, Solomon and Sonny Ramadhin.