In 1816, a little black girl called Eliza was uprooted from her home in Demerara and taken, by boat and by carriage, across the world.

This moving of melanated peoples wasn’t something particularly strange at the time, as by this point, the trans-Atlantic slave trade had seen over 12 million Africans brutally transported around the globe against their will.

The thing which was notable about Eliza’s story, was that she was not forced to the Caribbean or American colonies to work. Instead, along with her little brother William, she was brought to the Black Isle in Scotland.

The story of Eliza is explored in a new film of the same name by Angus McLeod and produced by Gaelic arts organisation, Fèisean nan Gàidheal with assistance from David Alston, a Cromarty-based historian who has been researching her life for over twenty years.

“Eliza’s story is the same as many black people’s from the time period. Her father, Hugh Junor, was a white slave and plantation owner, her mother was either a slave or a free black woman – it is unknown – who the children never saw again,” explained Alston.

“What is different for Eliza and William however, is that they had the opportunity – because of their father’s wishes – to receive an education, and have a life which many others of their background would not have had at the time.”

He added: “Only a tiny number of the children born to slave owners and enslaved or free women of colour were brought to Britain – but in 1804 almost one in ten of the pupils at Inverness Royal Academy was from the Caribbean (at least some of them were black).

“There were pupils with this background in Inverness, Cromarty, Fortrose, Tain, Dornoch, Elgin – and probably at the majority of the academies in Scotland.”

Eliza was just eleven when she left Demerara, on the north coast of South America, in early June 1816 for the six-week voyage to Scotland.

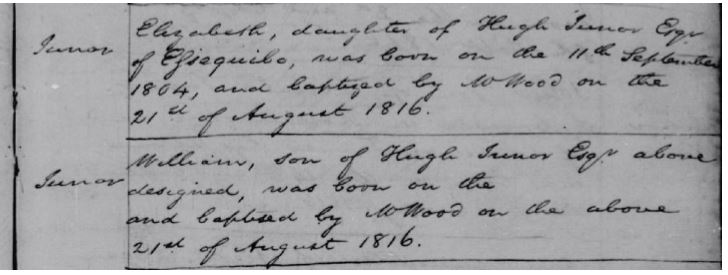

Just two months after arriving, she and William were baptised at Rosemarkie Parish Church in Fortrose.

“It was this odd double baptism which first introduced me to Eliza and led me to rescue her life from the obscurity of Scotland’s amnesia about its history of slave-ownership and slave-trading,” continued Alston.

“Now, in the welcome debates generated in 2020 by Black Lives Matter, she has emerged as a clear and visible sign to people in the Black Isle, and the wider Highlands, of the involvement of Highland Scots in the crimes of slavery.”

Although it is believed there were only around 70-80 working slaves actually living in Scotland at one time, about 30% of the slave plantations in the Caribbean were owned by Scots.

Lady Nugent – the wife of the governor – observed in Jamaica in 1801 that, “Almost all the agents, attorneys, merchants and shopkeepers, are of that country [Scotland] and really deserve to thrive in this, they are so industrious.”

Eliza’s father, Hugh, along with his partner, Alexander Henderson, were the joint ‘owners’ of 42 male and 33 female slaves.

Hugh also had his own slaves – a gang of 21 enslaved male carpenters, and one enslaved woman.

His own self-described “coloured children,” however were free to live a life in Scotland – albeit separate from their mother.

These strange nuances and hypocrisies in terms of race are explored in the film, as too are the increasing prejudices that arose towards black people in Britain during the 1800s, thanks in part to Scot, John Knox, described by historians as ‘the father of modern British racism.’

Eilidh McKenzie worked on creating the film with Angus McLeod and wrote one of the Gaelic songs in the piece, Oran Eliza.

She said: “Eliza’s father, Hugh Junor, played in the film by Black Isle resident Ronan MacColla, saw his actions in removing his children from South America to Scotland as honourable, in pursuit of a better education.

“The Reverend Archibald Brown, played by young Lewis actor Luke Macleod, was pro-slavery and step-father to Eliza, which seems rather incongruous.

“Finlay Maclennan from Inverness introduces us to the final character, Robert Knox who, although anti-slavery, nevertheless, germinated seeds of racism that survive down through the centuries.

“Eliza herself, portrayed by Edinburgh raised Tawana Maramba plays the part with a constant wistfulness for her mother.

“Of course, we do not know the circumstances of her removal from Guyana, but her vulnerability is something we felt should come through strongly and in a sense, this was aided by the fact that we had to record each actor individually and remotely due to the Covid restrictions in place during the filming period.”

David Alston has managed to piece together many snippets of Eliza’s life, and one part that stands out from her childhood in Fortrose is that she was awarded ‘proficiency in penmanship,’ although, sadly, she leaves no written record of how she, like so many of those with a similar fate, ever felt about her experiences.

Tawana Maramba, who plays Eliza in the film, however, has hazarded a guess.

“I think she must have felt scared, upset, and unsure about the future,” she said.

“She was forced to leave her mother at such a young age and did not know if she would ever see her again. Guyana was her home, so the thought of starting afresh somewhere new and the difference in culture must have been very daunting.

“Being a black woman and having an awareness of the history of slavery and racism, and based on my own personal research, I was able to put myself into her shoes and relate to how she might have felt.

“We also had an amazing script that I think really showed how she felt at these different moments and I was able to engage with it to portray these feelings and thoughts during her life. For example, her coming to terms with where her mother stood within society and how she too was going to face prejudice due to the colour of her skin.

“I think its imperative, more now than ever, that we relate and learn from stories like Eliza’s by embedding them in the education curriculum and initiating dialogue around diversity and cultural acceptance.

“I can only hope that this process of understanding and learning will eventually lead to acceptance and cultural inclusivity.”