We had a long running page but lost it. This is what I can find from archives

- First allowed to play on tour in 1961

We had a long running page but lost it. This is what I can find from archives

Replies sorted oldest to newest

* Interesting comment from Morgan Freeman.

Rev

Kenneth Manning / Published September 29, 1983

Ernest Everett Just

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Dr. Ernest Everett Just

10.5px

Born August 14, 1883

Charleston, South Carolina

Died October 27, 1941 (aged 57)

Washington D.C.

Residence United States, Italy, Germany, France

Nationality American

Fields biology, zoology, botany, history, and sociology

Institutions Howard University

Woods Hole, Massachusetts

Stazione Zoologica

Kaiser Wilhelm Institute

Station biologique de Roscoff

Alma mater Dartmouth College

University of Chicago

Doctoral advisor Frank R. Lillie

Known for marine biology

cytology

parthenogenesis

Notable awards Spingarn Medal (1915)

Ernest Everett Just (August 14, 1883 – October 27, 1941) was a pioneering African-American biologist, academic and science writer. Just's primary legacy is his recognition of the fundamental role of the cell surface in the development of organisms. In his work within marine biology, cytology and parthenogenesis, he advocated the study of whole cells under normal conditions, rather than simply breaking them apart in a laboratory setting. In addition, Just also left an everlasting impression within the African American community for his ability to pursue a high level of education in spite of the racial obstacles that he faced.

Contents

1 Early life

2 Founding of Omega Psi Phi

3 Career

4 Death

5 Legacy

6 References

7 Further reading

8 External links

Early life

Just was born in South Carolina to Charles Frazier Just Jr. and Mary Matthews Just on August 14, 1883. His father and grandfather, Charles Sr., were dock builders. When Ernest was four years old, both his father and grandfather died. Ernest's father died of alcoholism.[1] Just’s mother became the sole supporter of Just, his younger brother, and his younger sister. Mary Matthews Just taught at an African-American school in Charleston to support her family. During the summer, she worked in the phosphate mines on James Island. Noticing that there was much vacant land near the island, Mary persuaded several black families to move there to farm. The town they founded, now incorporated in the West Ashley area of Charleston, was eventually named Maryville in her honor.[2]

When Just was young he became dreadfully sick for six weeks with typhoid. Once the fever passed he had a hard time recuperating, his memory had been greatly affected. He had previously learned to read and write with a great amount of excellence for someone so young. Now he had to go through the process all over again. His mother had been very sympathetic in teaching him but after a while she gave up on him. Then one day he read his first page- by himself, this seemed miraculous. He kept his new secret to himself for a month before telling his mother because he felt she had hurt him with her unreasonable expectations.[3]

Hoping Just would become a teacher, his mother sent him to an all-black boarding school in Orangeburg, South Carolina at the age of thirteen. Believing that schools for blacks in the south were inferior, Just and his mother thought it better for him to go north. At the age of sixteen, Just enrolled at a Meriden, New Hampshire college-preparatory high school, Kimball Union Academy. During Just's second year at Kimball, he decided to return home for a visit only to hear that his mother had been buried an hour before he arrived.[3] Despite this hardship, Just completed the four-year program in only three years and graduated in 1903 with the highest grades in his class.[4]

Just went on to graduate magna cum laude from Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire.[5] Just won special honors in zoology, and distinguished himself in botany, history, and sociology as well. He was also honored as a Rufus Choate scholar for two years and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa.[4] Just was also a candidate to deliver a commencement speech, but was not chosen because faculty “decided it would be a faux pas to allow the only black in the graduating class to address the crowd of parents, alumni, and benefactors. It would have made too glaring the fact that Just had won just about every prize imaginable." [3]

Founding of Omega Psi Phi

On November 17, 1911, Ernest assisted three Howard students (Edgar Amos Love, Oscar James Cooper, and Frank Coleman), in establishing Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. Love, Cooper, and Coleman approached Just about establishing a black fraternity on campus. Howard's faculty and administration initially opposed the idea fearing a political threat this could pose to Howard's white administration. Despite the administration's initial doubts, Ernest Just worked to mediate the controversy. Omega Psi Phi, Alpha Chapter, was established on December 15, 1911.[1]

Career

When he graduated from Dartmouth, Just faced the same problems as all black college graduates of his time: no matter how brilliant they were or how high were their grades, it was almost impossible for blacks to become faculty members of white colleges or universities. Just then took what seemed to be the best choice available to him and was appointed to a teaching position at historically black Howard University in Washington, D.C. In 1910, he was put in charge of the newly formed biology department by Wilbur P. Thirkield. Just first began teaching rhetoric and English at Howard University in 1907, a field somewhat removed from his specialty. By 1909 he was teaching English, Biology and still later, Zoology.[6] In 1912, he became head of the Department of Zoology, a position he held until his death in 1941. Just was soon introduced to Dr. Frank R. Lillie, head of the biology department at the University of Chicago. Lillie, who was also chief of the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) at Woods Hole, Massachusetts, invited Just to spend the summer of 1909 as his research assistant at the MBL. For the next 20 years, Just spent every summer but one at MBL. On June 12, 1912, Ernest married Ethel Highwarden, who taught German at Howard University. They had three children: Margaret, Highwarden, and Maribel.

Just spent at least 20 summer sessions at Woods Hole, he learned to handle the material with skill and understanding, in time he was in great demand for those looking for advice and assistance in the field of biology.[7] In 1915, Just took a leave of absence from Howard to enroll in an advanced academic program at the University of Chicago. That same year, Just, who was gaining a national reputation as an outstanding young scientist, was the first recipient of the NAACP's Spingarn Medal on February 12, 1915, the medal recognized his scientific achievements and his “foremost service to his race." [3] He began his graduate training at the marine biological laboratory in 1909 with the course in marine invertebrates and in 1910 in embryology. In 1911-1912 he was a research assistant, his experiments focused on marine eggs, fertilization and breeding habits of the sea-urchin Arbacia. His duties at Howard delayed the completion of his work and receiving his Ph.D. degree at the University of Chicago until 1916.[7] In June 1916, Just received his Ph.D. in experimental embryology, with a thesis on the mechanics of fertilization, from the University of Chicago, becoming one of the handful of blacks who had gained this degree from a major university. By the time he got his Ph.D. in 1916, he had already co-authored a paper with Dr. Lillie.[6]

Just, however, became frustrated because he could not attain an appointment to a major American university. He wanted a position that would provide a steady income and allow him to spend more time with his research. Just’s scientific career was a constant struggle for opportunity for research, the breath of his life. He was condemned by race to remain attached to Howard, an institution that could not give him full opportunity to ambitions such as his.[7] The same year, he conducted experiments at the prestigious zoological station 'Anton Dohrn' in Naples, Italy. Then, in 1930, he became the first American to be invited to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin, Germany, where several Nobel Prize winners conducted research. Altogether from his first trip in 1929, Just made nine visits to Europe to pursue research. Scientists treated him like a celebrity and encouraged him to extend his theory on the ectoplasm to other species. [7] Just enjoyed traveling to Europe because he did not face as much discrimination there in comparison to the U.S. and when he did encounter racism, it came from two Americans.[3] Beginning in 1933, Just ceased his work in Germany when the Nazis began to take the control of the country. He relocated his European-based studies to Paris.

Just authored two books, Basic Methods for Experiments on Eggs of Marine Mammals (1922) and The Biology of the Cell Surface (1939), and he also published several scientific papers relating to cell cytoplasm.[8] Although Just’s experimental work showed an important role for the cell surface in development, it was largely and unfortunately ignored. This was true even with respect to scientists who emphasized the cell surface in their work. It was especially true of the Americans; with the Europeans he fared somewhat better.[7]

Death

At the outbreak of World War II, Ernest Just was working at the Station Biologique in Roscoff, France, researching the paper that would become Unsolved Problems of General Biology. Although the French government requested foreigners to evacuate the country, Just remained to complete his work. In 1940, Germany invaded France and Just was briefly imprisoned in a prisoner-of-war camp.[9] He was rescued by the U.S. State Department and returned to his home country in September 1940. However, Just had been very ill for months prior to his arrest and his condition deteriorated in prison and on the journey back to the U.S. In the fall of 1941, he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, and died shortly thereafter.[10]

Legacy

Just was the subject of the 1983 biography Black Apollo of Science: The Life of Ernest Everett Just by Kenneth R. Manning. The book received the 1983 Pfizer Award and was a finalist for the 1984 Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography.[11][12] Just has been featured in The Black Heritage Stamp series that began in 1978 honoring Afro-Americans great accomplishments. His stamp became available on February 1, 1996.[13]

In 1996, the U.S. Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp honoring Just.[13]

Beginning in 2000, the Medical University of South Carolina has hosted the annual Ernest E. Just Symposium to encourage non-white students to pursue careers in biomedical sciences and health professions.[14]

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante included Just on his list of the 100 Greatest African Americans.[15]

Just believed that "life as an event lies in a combination of chemical stuffs exhibiting physical properties; and it is in this combination, i.e., its behavior and activities, and in it alone that we can seek life."[16]

A pioneering African-American medical researcher, Dr. Charles R. Drew made some groundbreaking discoveries in the storage and processing of blood for transfusions. He also managed two of the largest blood banks during World War II. Drew grew up in Washington, D.C., as the oldest son of a carpet layer.

In his youth, Drew showed great athletic talent. He won several medals for swimming in his elementary years, and later branched out to football, basketball and other sports. After graduating from Dunbar High School in 1922, Drew went to Amherst College on a sports scholarship. There, he distinguished himself on the track and football teams.

Drew completed his bachelor's degree at Amherst in 1926, but didn't have enough money to pursue his dream of attending medical school. He worked as a biology instructor and a coach for Morgan College, now Morgan State University, in Baltimore for two years. In 1928, he applied to medical schools and enrolled at McGill University in Montreal, Canada.

At McGill University, Drew quickly proved to be a top student. He won a prize in neuroanatomy and was a member of the Alpha Omega Alpha, a medical honor society. Graduating in 1933, Drew was second in his class and earned both Doctor of Medicine and Master of Surgery degrees. He did his internship and residency at the Royal Victoria Hospital and the Montreal General Hospital. During this time, Drew studied with Dr. John Beattie, and they examined problems and issues regarding blood transfusions.

After his father's death, Drew returned to the United States. He became an instructor at Howard University's medical school in 1935. The following year, he did a surgery residence at Freedmen's Hospital in Washington, D.C., in addition to his work at the university.

In 1938, Drew received a Rockefeller Fellowship to study at Columbia University and train at the Presbyterian Hospital in New York City. There, he continued his exploration of blood-related matters with John Scudder. Drew developed a method for processing and preserving blood plasma, or blood without cells. Plasma lasts much longer than whole blood, making it possible to be stored or "banked" for longer periods of time. He discovered that the plasma could be dried and then reconstituted when needed. His research served as the basis of his doctorate thesis, "Banked Blood," and he received his doctorate degree in 1940. Drew became the first African-American to earn this degree from Columbia.

As World War II raged in Europe, Drew was asked to head up a special medical effort known as "Blood for Britain." He organized the collection and processing of blood plasma from several New York hospitals, and the shipments of these life-saving materials overseas to treat causalities in the war.2

Y'all cyan focus pun dem duh things. Me gun focus pun de important wans. Dis picha worth repostin' ![]()

We should archive every thread. It looks nicer.

I have admired this guy very much Sidney Poitier

guyana blacks have few heroes cuffy and rodney come to mind the present crops are all cowards.i wonder if kwame will celebrate black history month maybe nehru and rev can party with him

| Toni Morrison | |

|---|---|

Toni Morrison in 2008 | |

| Born | February 18, 1931 (age 82) Lorain, Ohio, United States |

| Occupation | Novelist, Writer |

| Genres | African American literature |

| Notable work(s) | Beloved, Song of Solomon, The Bluest Eye |

| Notable award(s) | Presidential Medal of Freedom 1988 |

BA Howard University

My high school health teacher. He was a scholar and a gentleman. He had all the traits I wish I had. He spent years mentoring me into the fine human I am today ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

God bless you Mr. Rennie!

My high school health teacher. He was a scholar and a gentleman. He had all the traits I wish I had. He spent years mentoring me into the fine human I am today ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

God bless you Mr. Rennie!

Delusional indeed.![]()

![]()

![]()

My high school health teacher. He was a scholar and a gentleman. He had all the traits I wish I had. He spent years mentoring me into the fine human I am today ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

God bless you Mr. Rennie!

Delusional indeed.![]()

![]()

![]()

Are you inferring that "fine human" and Shaitaan is an oxymoron?

My high school health teacher. He was a scholar and a gentleman. He had all the traits I wish I had. He spent years mentoring me into the fine human I am today ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

God bless you Mr. Rennie!

Delusional indeed.![]()

![]()

![]()

Are you inferring that "fine human" and Shaitaan is an oxymoron?

That man taught me to think and question. I owe my hatred of dogma, received wisdom, and distaste for appeals to authority to him.

too bad the poor chap failed! ![]()

but my congratulations to all the black teachers in Guyana who took the educational path to mould young lives.

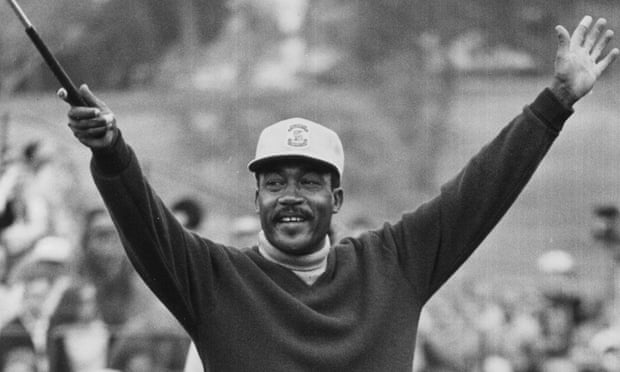

Charlie Sifford at the 1969 Los Angeles Open. Photograph: Anonymous/AP

Reuters

Wednesday 4 February 2015 14.48 GMT

Charlie Sifford, the first African American to play on the PGA Tour, died on Tuesday night at the age of 92, the PGA of America said.

“His love of golf, despite many barriers in his path, strengthened him as he became a beacon for diversity in our game,” PGA of America president Derek Sprague said. “By his courage, Dr Sifford inspired others to follow their dreams. Golf was fortunate to have had this exceptional American in our midst.”

Often called the Jackie Robinson of golf, Sifford broke golf’s color barrier when he was allowed to play on the tour in 1961. Sifford recorded two PGA wins, in 1967 and 1969, though he enjoyed many other victories in the prime of his golfing career prior to being allowed on tour.

Tiger Woods has often credited Sifford for paving the way for his own golfing path, and affectionately called him his ‘grandpa’.

Sifford’s trail-blazing career continued after his playing days. He became the first African American to be inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame in 2004 and was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in November last year. He was one of only three golfers to be awarded the medal, along with Jack Nicklaus and Arnold Palmer. “Charlie won tournaments, but more important, he broke a barrier,” Nicklaus once said. “I think what Charlie Sifford has brought to his game has been monumental.”

Sifford met Jackie Robinson as the player was attempting to break the color barrier in baseball. “He asked me if I was a quitter,” Sifford said in his autobiography, Just Let Me Play. “I told him no. He said, ‘If you’re not a quitter, you’re probably going to experience some things that will make you want to quit.’”

Sifford said his struggle for acceptance had been worth it, during an interview with AP in 2000. “If I hadn’t acted like a professional when they sent me out, if I did something crazy, there would never be any blacks playing,” he said. “I toughed it out. I’m proud of it. All those people were against me, and I’m looking down on them now.”

Kenneth Manning / Published September 29, 1983

Ernest Everett Just

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Dr. Ernest Everett Just

10.5px

Born August 14, 1883

Charleston, South Carolina

Died October 27, 1941 (aged 57)

Washington D.C.

Residence United States, Italy, Germany, France

Nationality American

Fields biology, zoology, botany, history, and sociology

Institutions Howard University

Woods Hole, Massachusetts

Stazione Zoologica

Kaiser Wilhelm Institute

Station biologique de Roscoff

Alma mater Dartmouth College

University of Chicago

Doctoral advisor Frank R. Lillie

Known for marine biology

cytology

parthenogenesis

Notable awards Spingarn Medal (1915)

Ernest Everett Just (August 14, 1883 – October 27, 1941) was a pioneering African-American biologist, academic and science writer. Just's primary legacy is his recognition of the fundamental role of the cell surface in the development of organisms. In his work within marine biology, cytology and parthenogenesis, he advocated the study of whole cells under normal conditions, rather than simply breaking them apart in a laboratory setting. In addition, Just also left an everlasting impression within the African American community for his ability to pursue a high level of education in spite of the racial obstacles that he faced.

Contents

1 Early life

2 Founding of Omega Psi Phi

3 Career

4 Death

5 Legacy

6 References

7 Further reading

8 External links

Early life

Just was born in South Carolina to Charles Frazier Just Jr. and Mary Matthews Just on August 14, 1883. His father and grandfather, Charles Sr., were dock builders. When Ernest was four years old, both his father and grandfather died. Ernest's father died of alcoholism.[1] Just’s mother became the sole supporter of Just, his younger brother, and his younger sister. Mary Matthews Just taught at an African-American school in Charleston to support her family. During the summer, she worked in the phosphate mines on James Island. Noticing that there was much vacant land near the island, Mary persuaded several black families to move there to farm. The town they founded, now incorporated in the West Ashley area of Charleston, was eventually named Maryville in her honor.[2]

When Just was young he became dreadfully sick for six weeks with typhoid. Once the fever passed he had a hard time recuperating, his memory had been greatly affected. He had previously learned to read and write with a great amount of excellence for someone so young. Now he had to go through the process all over again. His mother had been very sympathetic in teaching him but after a while she gave up on him. Then one day he read his first page- by himself, this seemed miraculous. He kept his new secret to himself for a month before telling his mother because he felt she had hurt him with her unreasonable expectations.[3]

Hoping Just would become a teacher, his mother sent him to an all-black boarding school in Orangeburg, South Carolina at the age of thirteen. Believing that schools for blacks in the south were inferior, Just and his mother thought it better for him to go north. At the age of sixteen, Just enrolled at a Meriden, New Hampshire college-preparatory high school, Kimball Union Academy. During Just's second year at Kimball, he decided to return home for a visit only to hear that his mother had been buried an hour before he arrived.[3] Despite this hardship, Just completed the four-year program in only three years and graduated in 1903 with the highest grades in his class.[4]

Just went on to graduate magna cum laude from Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire.[5] Just won special honors in zoology, and distinguished himself in botany, history, and sociology as well. He was also honored as a Rufus Choate scholar for two years and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa.[4] Just was also a candidate to deliver a commencement speech, but was not chosen because faculty “decided it would be a faux pas to allow the only black in the graduating class to address the crowd of parents, alumni, and benefactors. It would have made too glaring the fact that Just had won just about every prize imaginable." [3]

Founding of Omega Psi Phi

On November 17, 1911, Ernest assisted three Howard students (Edgar Amos Love, Oscar James Cooper, and Frank Coleman), in establishing Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. Love, Cooper, and Coleman approached Just about establishing a black fraternity on campus. Howard's faculty and administration initially opposed the idea fearing a political threat this could pose to Howard's white administration. Despite the administration's initial doubts, Ernest Just worked to mediate the controversy. Omega Psi Phi, Alpha Chapter, was established on December 15, 1911.[1]

Career

When he graduated from Dartmouth, Just faced the same problems as all black college graduates of his time: no matter how brilliant they were or how high were their grades, it was almost impossible for blacks to become faculty members of white colleges or universities. Just then took what seemed to be the best choice available to him and was appointed to a teaching position at historically black Howard University in Washington, D.C. In 1910, he was put in charge of the newly formed biology department by Wilbur P. Thirkield. Just first began teaching rhetoric and English at Howard University in 1907, a field somewhat removed from his specialty. By 1909 he was teaching English, Biology and still later, Zoology.[6] In 1912, he became head of the Department of Zoology, a position he held until his death in 1941. Just was soon introduced to Dr. Frank R. Lillie, head of the biology department at the University of Chicago. Lillie, who was also chief of the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) at Woods Hole, Massachusetts, invited Just to spend the summer of 1909 as his research assistant at the MBL. For the next 20 years, Just spent every summer but one at MBL. On June 12, 1912, Ernest married Ethel Highwarden, who taught German at Howard University. They had three children: Margaret, Highwarden, and Maribel.

Just spent at least 20 summer sessions at Woods Hole, he learned to handle the material with skill and understanding, in time he was in great demand for those looking for advice and assistance in the field of biology.[7] In 1915, Just took a leave of absence from Howard to enroll in an advanced academic program at the University of Chicago. That same year, Just, who was gaining a national reputation as an outstanding young scientist, was the first recipient of the NAACP's Spingarn Medal on February 12, 1915, the medal recognized his scientific achievements and his “foremost service to his race." [3] He began his graduate training at the marine biological laboratory in 1909 with the course in marine invertebrates and in 1910 in embryology. In 1911-1912 he was a research assistant, his experiments focused on marine eggs, fertilization and breeding habits of the sea-urchin Arbacia. His duties at Howard delayed the completion of his work and receiving his Ph.D. degree at the University of Chicago until 1916.[7] In June 1916, Just received his Ph.D. in experimental embryology, with a thesis on the mechanics of fertilization, from the University of Chicago, becoming one of the handful of blacks who had gained this degree from a major university. By the time he got his Ph.D. in 1916, he had already co-authored a paper with Dr. Lillie.[6]

Just, however, became frustrated because he could not attain an appointment to a major American university. He wanted a position that would provide a steady income and allow him to spend more time with his research. Just’s scientific career was a constant struggle for opportunity for research, the breath of his life. He was condemned by race to remain attached to Howard, an institution that could not give him full opportunity to ambitions such as his.[7] The same year, he conducted experiments at the prestigious zoological station 'Anton Dohrn' in Naples, Italy. Then, in 1930, he became the first American to be invited to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin, Germany, where several Nobel Prize winners conducted research. Altogether from his first trip in 1929, Just made nine visits to Europe to pursue research. Scientists treated him like a celebrity and encouraged him to extend his theory on the ectoplasm to other species. [7] Just enjoyed traveling to Europe because he did not face as much discrimination there in comparison to the U.S. and when he did encounter racism, it came from two Americans.[3] Beginning in 1933, Just ceased his work in Germany when the Nazis began to take the control of the country. He relocated his European-based studies to Paris.

Just authored two books, Basic Methods for Experiments on Eggs of Marine Mammals (1922) and The Biology of the Cell Surface (1939), and he also published several scientific papers relating to cell cytoplasm.[8] Although Just’s experimental work showed an important role for the cell surface in development, it was largely and unfortunately ignored. This was true even with respect to scientists who emphasized the cell surface in their work. It was especially true of the Americans; with the Europeans he fared somewhat better.[7]

Death

At the outbreak of World War II, Ernest Just was working at the Station Biologique in Roscoff, France, researching the paper that would become Unsolved Problems of General Biology. Although the French government requested foreigners to evacuate the country, Just remained to complete his work. In 1940, Germany invaded France and Just was briefly imprisoned in a prisoner-of-war camp.[9] He was rescued by the U.S. State Department and returned to his home country in September 1940. However, Just had been very ill for months prior to his arrest and his condition deteriorated in prison and on the journey back to the U.S. In the fall of 1941, he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, and died shortly thereafter.[10]

Legacy

Just was the subject of the 1983 biography Black Apollo of Science: The Life of Ernest Everett Just by Kenneth R. Manning. The book received the 1983 Pfizer Award and was a finalist for the 1984 Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography.[11][12] Just has been featured in The Black Heritage Stamp series that began in 1978 honoring Afro-Americans great accomplishments. His stamp became available on February 1, 1996.[13]

In 1996, the U.S. Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp honoring Just.[13]

Beginning in 2000, the Medical University of South Carolina has hosted the annual Ernest E. Just Symposium to encourage non-white students to pursue careers in biomedical sciences and health professions.[14]

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante included Just on his list of the 100 Greatest African Americans.[15]

Just believed that "life as an event lies in a combination of chemical stuffs exhibiting physical properties; and it is in this combination, i.e., its behavior and activities, and in it alone that we can seek life."[16]

I remember reading a book on this guy in 1987. He was a brilliant scientist. He was married to a German woman who helped him get released from a NAZI prison camp and saved his life.

Despite freedom of information act requests throughout the years, New York still will not release records to the public and claim files would endanger the safety of police officers and constitute unwarranted invasions of privacy

Malcolm X in Rochester, New York, 1965. Photograph: Michael Ochs Archives/Michael Ochs Archives

Garrett Felber

Fifty years on, questions surrounding Malcolm X’s assassination still contribute to the atmosphere of suspicion and distrust between law enforcement and the black community. And while the murders of John F Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr, and Emmett Till have all been re-examined through federal intervention, Malcolm X’s assassination remains a blindspot in US jurisprudence and historical memory.

Malcolm X was a dangerous man. Not dangerous as the widely circulated image of him holding a rifle and peeking through the curtains in his home would suggest. Nor because he disagreed with the nonviolent wing of the civil rights movement and its assertion that racial integration was the primary objective of the black freedom struggle. By challenging integration as a primary goal, Malcolm X threatened to undermine the tenuous support that mainstream civil rights leaders were receiving from the government and white liberals. For many white people, Malcolm and the Nation of Islam embodied their greatest fears.

As the public face of the National of Islam, he confronted racism well beyond the confines of southern segregation. He worked tirelessly to denounce America as a damaging imperialist and neo-colonialist system. “Just as a chicken cannot produce a duck egg”, he charged, “the system in this country cannot produce freedom for an Afro-American.” And with his characteristic wit, he added that if it did, “you would say it was certainly a revolutionary chicken.”

By 1963, Malcolm had been suspended from the NOI for calling President Kennedy’s assassination a case of “chickens coming home to roost.” The rift deepened after Malcolm revealed that the group’s leader, Elijah Muhammad, had fathered children out-of-wedlock with NOI secretaries. This public feud combined with competing political visions to cause deep divisions within the Muslim community. Malcolm formed two independent groups in 1964: the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU) and Muslim Mosque, Inc. (MMI). A year later, he prepared to release a new political program which would have likely included voter registration drives, local organizing against police brutality, and a call for the United Nations to denounce American racial practices as human rights violations. He was gunned down on the very day he was set to unveil it.

When Malcolm X was killed at the Audubon Ballroom on 21 February 1965, a man named Talmadge Hayer (now named Mujahid Abdul Halim) was pulled from the scene of the crime. Yet some witnesses claimed a second figure was also taken into custody by the police.

The late Herman Ferguson, a founding member of the Organization of Afro-American Unity (the OAAU, founded by Malcolm X after he left the Nation of Islam), recalled a police car which pulled up alongside the ballroom and brought out a man with an “olive complexion ... obviously in great pain.” Ferguson, thinking that the injured man was one of “our guys,” watched as the squad car sped away and over the Hudson River. The Associated Press also reported the day after the assassination that “two men were taken into custody.”

In the following days, the NYPD also arrested two other members of the Nation of Islam’s Mosque 7 in Harlem: Norman 3X Butler (Muhammad Abd Al-Aziz) and Thomas 15X Johnson (Khalil Islam). Both men, as well as key witnesses who knew them, denied they were at the ballroom that day. Hayer also testified at the end of the 1966 trial that the two men had not been involved. But he refused to name any other accomplices, and all three received life sentences.

A decade into his incarceration, Hayer came forward with new information, identifying four co-conspirators. He signed an affidavit offering the names and addresses of these men, along with a detailed timeline of their plot. With the help of the self-described “radical attorney” William Kunstler, Butler and Johnson appealed their convictions.

Hayer named William Bradley, a NOI member called Willie X, as the man who fired the fatal shotgun blast, adding that Bradley was “known as a stick-up man.” The petition noted that Bradley was “upon information and belief presently incarcerated in the Essex County Jail, Caldwell, New Jersey.” Kunstler added that he did not know of “any comparable case in American jurisprudential history” in which an accomplice had described a crime in such detail without a thorough reinvestigation. Yet, judge Harold Rothwax rejected a motion to reopen the case.

Bradley (who now goes by Al-Mustafa Shabazz) is living in Newark. Earlier this week, The New York Daily News published an interview with him in which he rejected the claims. “It’s an accusation,” he said. “They never spoke to me. They just accused me of something I didn’t do.”

‘The investigation was botched’

In the weeks following Malcolm’s assassination, the organizations he created after his falling out with the Nation of Islam struggled without his leadership, and his friends and comrades attempted to make sense of their loss. Most of his followers had witnessed the murder, and the dangerous climate and mistrust of the aftermath drove some underground for decades.

On 6 March 1965, members gathered for the weekly Saturday class at the OAAU’s Liberation School. That meeting had been lost to history until recently, when a detailed account reveal its contents. In 2011, the personal papers of James Campbell, housed at the College of Charleston’s Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture, were made available to the general public.

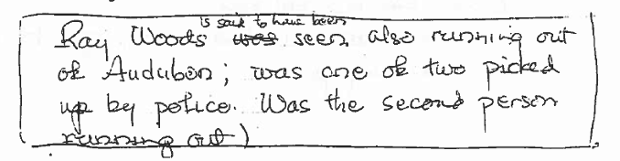

Campbell is an educator and civil rights activist who founded the Liberation School along with OAAU member Herman Ferguson in 1964. His papers include handwritten notes taken by the late Japanese American activist Yuri Kochiyama. The meeting, the notes explain, was held “to establish stability from this crisis.” And the notes contain an unexpected piece of information. Kochiyama’s scrawl at the bottom of the 6 March meeting reads:

‘Ray Woods is said to have been seen also running out of Audubon; was one of two picked up by police. Was the second person running out.’

‘Ray Woods is said to have been seen also running out of Audubon; was one of two picked up by police. Was the second person running out.’ The notes appear to substantiate the accounts of Herman Ferguson and the AP of a “second man” taken into police custody. That a name should resurface 50 years later is remarkable. But more significant is that the “Ray Woods” named in the note was likely Raymond A Wood, an undercover New York City police officer with the Bureau of Special Services and Investigation (BOSSI).

Wood began his career by infiltrating the Bronx Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) chapter under the name Ray Woodall in 1964. There, he posed as a 27 year-old graduate of Manhattan College studying law at Fordham. He was soon named CORE’s housing chairman and oversaw a voter registration project.

Wood earned his activist bonafides by getting arrested with two others at city hall while attempting a citizen’s arrest of mayor Wagner for allowing racial discrimination on a public construction project. Feminist Susan Brownmiller, a fellow CORE activist at the time, recalled that if “CORE had placed an advertisement in the Amsterdam News describing what it was looking for, Woodall would have fit the bill.”

By 1965, “Woodall” had been reassigned under his real name to infiltrate a group calling itself the Black Liberation Movement (BLM). He was credited with foiling a bomb plot by the BLM that allegedly targeted the Statue of Liberty and other national monuments, just a week before Malcolm X’s assassination. One of the four arrested in the plot was Walter Bowe, who also co-chaired the cultural committee in Malcolm’s OAAU. Wood’s close association with an OAAU member makes it likely that others within the organization would also have known and recognized him.

Wood was promoted to detective second grade for making the arrests in the BLM case. And although his name and a photo of the back of his head circulated throughout the press in the week leading up to Malcolm X’s assassination, the NYPD reported that he was put back to work because his “face is still a secret.”

Agent Wood hides face from photographer. Photograph: Star.

Agent Wood hides face from photographer. Photograph: Star. There is no question that the police were keeping close tabs on Malcolm X in the period prior to his assassination. Tony Bouza, a former BOSSI detective and lieutenant from 1957 to 1965, explains that the NYPD, and not the FBI, was the primary agency conducting this surveillance. Gene Roberts – a man known affectionately within the OAAU as “Brother Gene” and photographed trying in vain to resuscitate Malcolm X at the assassination – was later confirmed as an undercover agent.

Bouza argues that the NYPD failed to take basic and minimal steps to protect a prominent public figure from a threat that was widely believed to be imminent. And he is harshly critical of its subsequent failure to disclose all that it knew about the assassination of Malcolm X. “The investigation was botched,” he said, and a “parallel tragedy lies in the NYPD’s obvious stonewalling of any release of records.”

But Bouza also insists that Wood had nothing to do with the case, and there are other reasons to doubt this latest eyewitness account placing Ray Wood at the Audubon. Such reports are unreliable, even those recorded shortly after the assassination. Accounts of what happened at the Audubon Ballroom that day are also conflicting. One OAAU member named Willie Harris was interviewed by the NYPD while being treated at a medical center after a stray bullet hit him at the ballroom. Harris claims he sought help from a police officer who then took him to the hospital. Is it possible that the unnamed witness mistook Harris for Ray Wood? Finally, there is the question of why BOSSI would send an undercover agent back into a place where he might be recognized after his name had been in the press.

The simplest way to resolve these questions would be for the NYPD to release its surveillance files and disclose what Ray Wood, Gene Roberts, and its other undercover officers reported in the years surrounding the assassination. But the department has repeatedly refused to release them.

My attempts with professor Manning Marable and the Malcolm X Project at Columbia University in 2008-2009 to access BOSSI files through the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) ended in a full denial. In denying the requests, the department’s legal bureau cited a number of Public Officers Laws, claiming that the files would endanger the safety of officers and constitute unwarranted invasions of privacy. A more recent FOIA request this year produced some materials relating to the assassination case, but only documents that were already publicly available at the New York Municipal Archives. The release did not include any files related to BOSSI’s surveillance.

The most obvious avenue for reopening the investigation into Malcolm X’s assassination is the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act. In 2011, the Justice Department responded to calls to reopen the case with the statement that “the matter does not implicate federal interests sufficient to necessitate the use of scarce federal investigative resources into a matter for which there can be no federal criminal prosecution.” The Till Act, however, was specifically crafted to render these objections moot. It allocates $10m annually for such investigations, and requires the Justice Department to work in concert with local law enforcement to implement state law.

Janis McDonald, who co-directs the Cold Case Justice Initiative at Syracuse University College of Law, told me that rulings such as this ignore “the intent of Congress when the Emmett Till Act was enacted.” Its implementation, she said, “has been a failed promise to the families of those who were killed and a disregard of the congressional intent to preserve the integrity of the law for everyone. This Act has never been a priority for the Department of Justice.” It is set to expire in 2017 if not renewed by Congress.

According to Paula Johnson, co-director of the Syracuse Cold Case Justice Initiative, the “purpose of the Emmett Till Act is to fully investigate and resolve just such killings.” The account placing Ray Wood at the scene, she said, “warrants further investigation into the knowledge or role of law enforcement in Malcolm X’s death.”

Until Malcolm X’s assassination case is reopened and surveillance files are made fully available, the injustice to one of America’s boldest civil rights figure continues, while one or more of his killers may roam free.

As the case turns 50 this week, the NYPD and other surveillance agencies must make their records public. It is time to for a new investigation into the assassination of this civil rights leader that will lay to rest the lingering questions about the case, and ensure that all those involved have been brought to justice.

Garrett Felber is a doctoral candidate at the University of Michigan. He was Senior Research Advisor at the Malcolm X Project at Columbia University and is co-author of The Portable Malcolm X Reader with Manning Marable.

25 February, 2015, Source - TeleSur TV

Carter G. Woodson began Negro History Week in 1926 to coincide with the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln on February 12 and Frederick Douglass on February 14.

"If a race has no history, it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated.”

In the heady days of Black radical movements globally, the Black United Students at Kent State University, expanded Black History Week to Black History Month in 1969.

President Gerald Ford urged U.S. citizens in 1976, as part of the biennial celebration of the country's founding, to "seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history."

February is not only about Lincoln and Douglass

It has become the anniversary of Malcolm X's assassination and the month when a black boy, Trayvon Martin was brutally killed by George Zimmerman in 2012.

Ferguson Action, the prominent social movement that uses protests and public resistance to oppose police violence, in 2015 declared that February will no longer be known as Black History month, because, “Black History Month has become a sanitized and corporatized version of the black experience in this country.

February has become a retelling of black facts removed from black struggle. Lost are the stories of shared struggle, forgotten is the courage of common people during uncommon moments.”

Instead they have announced that this February “and all Februaries #BlackFutureMonth.”

They explain that “our history and our future is not a single narrative, but a mosaic of experiences.”

This re-articulation of February has inspired not #BlackLivesMatter activists and cultural workers, who are imagining what does blackness mean in the future. What does Black survival and Black genius look like. As Black communities fight daily for their right to exist in a future. “.... a future where black lives matter, black love reigns, and black people are free.”

21 febrero 2015 - 10:45 PM, Source - TelSur TV

The United Nations, which declared the decade beginning in 2015 for “People of African Descent,” estimates that there are approximately 200 million people that identify of African descent in the Americas and millions more in other parts of the world outside of the African continent.

The decade seeks ‘‘to promote respect, protection and fulfillment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms for people of African descent.’’ The next ten years present an opportunity to challenge more than 500 years of invasion, exploitation and genocide.

The platform was developed and proposed by organizations that attended the UN conference against racial discrimination in 2001 in Durban, South Africa. The Durban Declaration and Program of Action “acknowledged that people of African descent were victims of slavery, the slave trade and colonialism, and continue to be victims of their consequences.”

During the month of February, North America commemorates Black History Month to reflect on the contributions as well as the history of struggle of black people in the United States and Canada. But this should not just be a question of the past, as there forms of oppression against black communities have continued, as thus, so has organizing against them.

Activists in North America see the struggle for justice in Black communities in the United States as a worldwide call to transform the conditions for peoples of African descent internationally.

As Alicia Garza, one of the founders of #BlackLivesMatter writes in A Herstory of the #BlackLivesMatter Movement, “Black Lives Matter is an ideological and political intervention in a world where Black lives are systematically and intentionally targeted for demise. It is an affirmation of Black folks’ contributions to this society, our humanity, and our resilience in the face of deadly oppression.”

While global attention has been focused on the continuous wave of protests in the United States against police brutality and violence in Black communities, there are ongoing Black led struggles across Latin America and the Caribbean – home to the largest populations of African descendants outside of Africa – including:

Honduras' Garifuna Reclaim Indigenous Rights

Since a 2009 military coup, the Honduran people have led a national resistance front against ongoing state violence.

The Garifuna nation, an afro-indigenous people who reside along the country's north coast, have resisted centuries of continuous threats. The current administration's neoliberal economic policies threaten the ancestral makeup of Garifuna communities as mega tourism projects and privatized cities promise to displace entire families, destroy local economies and irreversibly damage the Garifuna’s land and sea.

Under the leadership of the Black Fraternal Organization of Honduras (OFRANEH), the Garifuna have three legal cases against the Honduran state at the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. OFRANEH has worked with all 46 Garifuna communities in Honduras and internationally with the Garifuna diaspora to protect their nation’s indigenous rights.

The Garifuna argue that the Honduran state intentionally and systematically ignores their nation’s rights, which are protected under the International Labor Organization’s Convention 169 and the United Nations Declaration on Human Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The Honduran state has attempted to deny the Garifuna their rights by negating their indigenous ancestry.

The Garifuna are currently awaiting the IACHR’s ruling, which promise to break new political ground for indigenous nations internationally.

Caribbean Nations Demand Reparations

Reparations have been an ongoing struggle for African descents since the emergence of the first black republic in Haiti. Across the region, reparations have been one of the most consistent demands for Black communities that have been marginalized and disenfranchised by European colonialism and ongoing oppression.

Currently, 15 Caribbean nations have demanded reparations from European nations responsible for the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. At the last Bolivarian Alliance for the People of Our Americas (ALBA) Summit, Prime Minister of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Ralph Gonselves advocated for members nations to assume the struggle for reparations.

Earlier this year in an interview with the Guardian, Sir Hilary Beckles, who chairs the reparations task force said “Contrary to the British media, we are not exclusively concerned with financial transactions, we are concerned more with justice for the people who continue to suffer harm at so many levels of social life.”

Some of the demands include diplomatic help with nations such as Ghana and Ethiopia, support for cultural exchanges between the Caribbean and West Africa, as well as provide medical assistance for the Caribbean Community (Caricom) nations linked to the consequences of slavery.

Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs

and Emergency Relief Coordinator

Valerie Ann Amos, Baroness Amos, PC (born 13 March 1954) is the eighth and current UN Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator. Before her appointment to the UN, she had been British High Commissioner to Australia. She was made a Labour life peer in 1997 and served as Leader of the House of Lords and Lord President of the Council.

When Amos was appointed Secretary of State for International Development on 12 May 2003, following the resignation of Clare Short, she became the first black woman to sit in the Cabinet of the United Kingdom. She left the Cabinet when Gordon Brown became Prime Minister. She was then nominated to become the European Union Special Representative to the African Union by Brown.[1] In July 2010 Secretary-General of the United Nations Ban Ki-moon announced Baroness Amos's appointment to the role of Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator.[2]

Amos was born in British Guiana (now Guyana) in South America and attended Bexley Technical High School for Girls (now Townley Grammar School), Bexleyheath, where she was the first black deputy head girl. She completed a degree in Sociology at the University of Warwick (1973–76), and also later took courses in cultural studies at the University of Birmingham and the University of East Anglia.

After working in Equal Opportunities, Training and Management Services in local government in the London boroughs of Lambeth, Camden and Hackney, Amos became Chief Executive of the Equal Opportunities Commission 1989–94.

In 1995 Amos co-founded Amos Fraser Bernard and was an adviser to the South African government on public service reform, human rights and employment equity.

Amos has also been Deputy Chair of the Runnymede Trust (1990–98), a Trustee of the Institute for Public Policy Research, a non-executive Director of the University College London Hospitals Trust, a Trustee of Voluntary Services Overseas, Chair of the Afiya Trust, a director of Hampstead Theatre and Chair of the Board of Governors of the Royal College of Nursing Institute.

Amos was created a life peer in August 1997 as Baroness Amos, of Brondesbury in the London Borough of Brent.[citation needed] In the House of Lords she was a co-opted member of the Select Committee on European Communities Sub-Committee F (Social Affairs, Education and Home Affairs) 1997–98. From 1998 to 2001 she was a Government whip in the House of Lords and also a spokesperson on Social Security, International Development and Women's Issues as well as one of the Government's spokespersons in the House of Lords on Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs. Baroness Amos was appointed Parliamentary Under-Secretary for Foreign & Commonwealth Affairs on 11 June 2001, with responsibility for Africa; Commonwealth; Caribbean; Overseas Territories; Consular Issues and FCO Personnel. She was replaced by Chris Mullin.

Baroness Amos was made International Development Secretary after the incumbent, Clare Short, resigned from the post in the run-up to the US and UK 2003 invasion of Iraq. Although she ostensibly worked in development, she toured African countries that held rotating membership of the Security Council, encouraging them to support the attack. Despite her efforts, the UK was not successful in establishing a legal basis for the war.

Baroness Amos was made Leader of the House of Lords on 6 October 2003, following the death of Lord Williams of Mostyn, which meant that her tenure as Secretary of State for International Development lasted less than six months.

On 17 February 2005, the British government nominated Amos to head the United Nations Development Programme.

Baroness Amos left the cabinet when Gordon Brown took over as Prime Minister from Tony Blair in June 2007. Brown proposed her as the European Union special representative to the African Union, but this job went to Belgian career diplomat Koen Vervaeke instead. She was a member of the Committee on Commonwealth Membership, which presented its report on potential changes in membership criteria for the Commonwealth of Nations at the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting 2007 in Kampala, Uganda.

On 8 October 2008 it was reported that Amos was to join the Football Association's management board for England's bid to host the 2018 World Cup. This was described as a "surprise appointment", since she has no recorded interest in football (despite her interest in cricket) or any experience in similar work such as the 2012 Olympics bid.

On 4 July 2009 it was advised that Baroness Amos had been appointed British High Commissioner to Australia in succession to High Commissioner Helen Liddell. Amos took up the position in October 2009.

In 2010 United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon announced Amos's appointment as Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator. In March 2012 she visited Syria on behalf of the UN to press the Syrian government to allow access to all parts of Syria to help people affected by the 2011-2012 Syrian uprising. On 26. Nov 2014 NYT and CNN reported that according to Ban Ki-moon she is resigning her post.

She was awarded an Honorary Professorship at Thames Valley University in 1995 in recognition of her work on equality and social justice. On 1 July 2010, Amos received an honorary Doctorate of the University from the University of Stirling in recognition of her "outstanding service to our society and her role as a model of leadership and success for women today.

She was also awarded honorary degrees of Doctor of Laws from the University of Warwick in 2000 and the University of Leicester in 2006.

At the University of Birmingham Guild of Students (where she studied), one of the committee rooms is named "The Amos Room" after her, in acknowledgement of her services to society.

Amos is an enthusiast of cricket and talked about her love of the game with Jonathan Agnew on Test Match Special during the lunch break of the first day of the England v New Zealand test at Old Trafford in May 2008.

After resigning from the cabinet, Baroness Amos took up a directorship with Travant Capital, a Nigerian private equity fund launched in 2007.

In the House of Lords Register of Members Interests she lists this directorship as remunerated. At launch over one third of Travant’s first equity fund came from CDC (a government-owned plc). CDC's investment decisions are taken completely independently of external influences (including its shareholder) and the decision to invest in Travant by CDC was taken before Amos was appointed to the board of Travant.

Baroness Amos has never married and has no children. She was listed as one of "the 50 best-dressed over-50s" by the Guardian in March 2013.

Shirley Chisholm in 1972

Shirley Anita St. Hill Chisholm (November 30, 1924 – January 1, 2005) was an American politician, educator, and author.[1] She was a Congresswoman, representing New York's 12th Congressional District for seven terms from 1969 to 1983. In 1968, she became the first African-American woman elected to Congress. On January 25, 1972, she became the first major-party black candidate for President of the United States and the first woman to run for the Democratic presidential nomination (US Senator Margaret Chase Smith had previously run for the 1964 Republican presidential nomination).[2] She received 152 first-ballot votes at the 1972 Democratic National Convention

Shirley Anita St. Hill was born in Brooklyn, New York, to immigrant parents.[4] She had three younger sisters. Her father, Charles Christopher St. Hill, was born in British Guiana and arrived in the United States via Antilla, Cuba, on April 10, 1923, aboard the S.S. Munamar in New York City.[6] Her mother, Ruby Seale, was born in Christ Church, Barbados, and arrived in New York City aboard the S.S. Pocone on March 8, 1921. He was a worker in a factory that made burlap bags and she was a seamstress and did domestic work.

At age three, Shirley was sent to Barbados to live with her maternal grandmother, Emaline Seale, in Christ Church, where she attended the Vauxhall Primary School. She did not return until roughly seven years later when she arrived in New York City on May 19, 1934, aboard the S.S. Narissa.[9] As a result, she spoke with a partial West Indian accent throughout her life.[5] In her 1970 autobiography Unbought and Unbossed, she wrote: "Years later I would know what an important gift my parents had given me by seeing to it that I had my early education in the strict, traditional, British-style schools of Barbados. If I speak and write easily now, that early education is the main reason."

Beginning in 1939, Shirley attended Girls' High School in the Bedford–Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, a highly regarded, integrated school that attracted girls from throughout Brooklyn. She earned her Bachelor of Arts from Brooklyn College in 1946. There, she won prizes for her debating skills. She was a member of the Delta Sigma Theta sorority.

She met Conrad O. Chisholm in the late 1940s. He had come to the U.S. from Jamaica in 1946 and would later become a private investigator who specialized in negligence-based lawsuits. They married in 1949 in a large West Indian-style wedding.

Shirley Chisholm taught in a nursery school while furthering her education, earning her MA from Teachers College at Columbia University in elementary education in 1952.

From 1953 to 1959, she was director of the Friends Day Nursery in Brownsville, Brooklyn, and of the Hamilton-Madison Child Care Center in lower Manhattan.[8] From 1959 to 1964, she was an educational consultant for the Division of Day Care. She became known as an authority on issues involving early education and child welfare.

Running a day care center got her interested in politics, and during this time she formed the basis of her political career, working as a volunteer for white-dominated political clubs in Brooklyn, and with the Bedford-Stuyvesant Political League and the League of Women Voters

Chisholm was a Democratic member of the New York State Assembly from 1965 to 1968, sitting in the 175th, 176th and 177th New York State Legislatures. Her successes in the legislature included getting unemployment benefits extended to domestic workers. She also sponsored the introduction of a SEEK program (Search for Education, Elevation and Knowledge) to the state, which provided disadvantaged students the chance to enter college while receiving intensive remedial education.

In August 1968, she was elected as the Democratic National Committeewoman from New York State.

In 1968 she ran for the U.S. House of Representatives from New York's 12th congressional district, which as part of a court-mandated reapportionment plan had been significantly redrawn to focus on Bedford-Stuyvesant and was thus expected to result in Brooklyn's first black member of Congress. (As a result, the white incumbent in the former 12th, Representative Edna F. Kelly, sought re-election in a different district. Chisholm announced her candidacy around January 1968 and established some early organizational support. Her campaign slogan was "Unbought and unbossed". In the June 18, 1968, Democratic primary, Chisholm defeated two other black opponents, State Senator William S. Thompson and labor official Dollie Robertson. In the general election, she staged an upset victory over James L. Farmer, Jr., the former director of the Congress of Racial Equality who was running as a Liberal Party candidate with Republican support, winning by an approximately two-to-one margin. Chisholm thereby became the first black woman elected to Congress.

Chisholm was assigned to the House Agricultural Committee. Given her urban district, she felt the placement was irrelevant to her constituents. When Chisholm confided to Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson that she was upset and insulted by her assignment, Schneerson suggested that she use the surplus food to help the poor and hungry. Chisholm subsequently met Robert Dole, and worked to expand the food stamp program. She later played a critical role in the creation of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) program. Chisholm would credit Schneerson for the fact that so many "poor babies [now] have milk and poor children have food." Chisholm was then also placed on the Veterans' Affairs Committee. Soon after, she voted for Hale Boggs as House Majority Leader over John Conyers. As a reward for her support, Boggs assigned her to the much-prized Education and Labor Committee, which was her preferred committee. She was the third highest-ranking member of this committee when she retired from Congress.

All those Chisholm hired for her office were women; half of these were African-American.[2] Chisholm said that she had faced much more discrimination during her New York legislative career because she was a woman than because of her race.

Chisholm joined the Congressional Black Caucus in 1971 as one of its founding members.[18] In the same year, she was also a founding member of the National Women's Political Caucus.

In May 1971 she, along with fellow New York Congresswoman Bella Abzug, introduced a bill to provide $10 billion in federal funds for child care services by 1975.[19] A less expensive version introduced by Senator Walter Mondale[19] eventually passed the House and Senate as the Comprehensive Child Development Bill, but was vetoed by President Richard Nixon in December 1971, who said it was too expensive and would undermine the institution of the family.

In the 1972 U.S. presidential election, she made a bid for the Democratic Party's presidential nomination. She began exploring her candidacy in July 1971 and formally announced it on January 25, 1972, in a Baptist church in her district in Brooklyn. There she called for a "bloodless revolution" at the forthcoming Democratic nomination convention.

Her campaign was poorly organized and underfunded from the start; she only spent $300,000 in total. She also struggled to be regarded as a serious candidate instead of as a symbolic actor; she was ignored by much of the Democratic political establishment and received little support from her black male colleagues. Many headlines constructed Chisholm as an emasculating matriarch with headlines such as the Boston Globe’s “Rep. Shirley Chisholm outflanks her black political brothers”. She later reiterated, "When I ran for the Congress, when I ran for president, I met more discrimination as a woman than for being black. Men are men." In particular, she expressed frustration about the "black matriarch thing", saying, "They think I am trying to take power from them. The black man must step forward, but that doesn't mean the black woman must step back."[5] Her husband, however, was fully supportive of her candidacy and said, "I have no hangups about a woman running for president."

Chisholm skipped the initial March 7 New Hampshire contest, instead focusing on the March 14 Florida primary, which she thought would be receptive due to its "blacks, youth and a strong women's movement". But due to organizational difficulties and Congressional responsibilities, she only made two campaign swings there and ended with 3.5 percent of the vote for a seventh-place finish. Chisholm had difficulties gaining ballot access, but campaigned or received votes in primaries in fourteen states. Her most number of votes came in the June 6 California primary, where she received 157,435 votes for 4.4 percent and a fourth-place finish, while her best percentage in a competitive primary came in the May 6 North Carolina one, where she got 7.5 percent for a third-place finish. Overall, she won 28 delegates during the primaries process itself. Chisholm's base of support was ethnically diverse and included the National Organization for Women. Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem attempted to run as Chisholm delegates in New York. Altogether during the primary season, she received 430,703 votes, which was 2.7 percent of the total of nearly 16 million cast and represented seventh place among the Democratic contenders.

At the 1972 Democratic National Convention in Miami Beach, Florida, there were still efforts taking place by the campaign of former Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey to stop the nomination of Senator George McGovern. After that failed and McGovern's nomination was assured, as a symbolic gesture, Humphrey released his black delegates to Chisholm. This, combined with defections from disenchanted delegates from other candidates, as well as the delegates she had won in the primaries, gave her a total of 152 first-ballot votes for the nomination during the July 12 roll call. (Her precise total was 151.95. Her largest support overall came from Ohio, with 23 delegates (slightly more than half of them white), even though she had not been on the ballot in the May 2 primary there. Her total gave her fourth place in the roll call tally, behind McGovern's winning total of 1,728 delegates. Chisholm said she ran for the office "in spite of hopeless odds ... to demonstrate the sheer will and refusal to accept the status quo."[11] Among the volunteers who were inspired by her campaign was Barbara Lee, who continued to be politically active and was elected as a congresswoman 25 years later.

It is sometimes stated that Chisholm won a primary during 1972, or won three states overall, with New Jersey, Louisiana, and Mississippi being so identified. None of these fit the usual definition of winning a plurality of the contested popular vote or delegate allocations at the time of a state primary or caucus or state convention. In the June 6 New Jersey primary, there was a complex ballot that featured both a delegate selection vote and a non-binding, non-delegate-producing "beauty contest" presidential preference vote.[27] In the delegate selection vote, Democratic front-runner Senator George McGovern defeated his main rival at that point, Senator Hubert H. Humphrey, and won the large share of available delegates. Most of the Democratic candidates were not on the preference ballot, including McGovern and Humphrey; of the two that were, Chisholm and former governor of North Carolina Terry Sanford, Sanford had withdrawn from the contest three weeks earlier. In the actual preference ballot voting, which the Associated Press described as "meaningless", Chisholm received the majority of votes: 51,433, which was 66.9 percent. During the actual balloting at the national convention, Chisholm received votes from only 4 of New Jersey's 109 delegates, with 89 going to McGovern. In the May 13 Louisiana caucuses, there was a battle between forces of McGovern and Governor George Wallace; nearly all of the delegates chosen were those who identified as uncommitted, many of the black. Leading up to the convention, McGovern was thought to control 20 of Louisiana's 44 delegates, with most of the rest uncommitted. During the actual roll call at the national convention, Louisiana passed at first, then cast 18½ of its 44 votes for Chisholm, with the next best finishers being McGovern and Senator Henry M. Jackson with 10¼ each. As one delegate explained, "Our strategy was to give Shirley our votes for sentimental reasons on the first ballot. However, if our votes would have made the difference, we would have gone with McGovern." In Mississippi, there were two rival party factions that each selected delegates at their own state conventions and caucuses: "regulars" representing the mostly white state Democratic Party and "loyalists" representing many blacks and white liberals. Each slate professed to be largely uncommitted, but the regulars were thought to favor Wallace and the loyalists McGovern. By the time of the national convention, the loyalists were seated following a credentials challenge, and their delegates were characterized as mostly supporting McGovern, with some support for Humphrey. During the actual balloting, Mississippi went in the first half of the roll call, and cast 12 of its 25 votes for Chisholm, with McGovern coming next with 10 votes.

During the campaign the German filmmaker Peter Lilienthal shot the documentary film Shirley Chisholm for President for German Television channel ZDF.

Chisholm created controversy when she visited rival and ideological opposite George Wallace in the hospital soon after his shooting in May 1972, during the 1972 presidential primary campaign. Several years later, when Chisholm worked on a bill to give domestic workers the right to a minimum wage, Wallace helped gain votes of enough Southern congressmen to push the legislation through the House.

From 1977 to 1981, during the 95th Congress and 96th Congress, Chisholm was elected to a position in the House Democratic leadership, as Secretary of the House Democratic Caucus.

Throughout her tenure in Congress, Chisholm worked to improve opportunities for inner-city residents. She was a vocal opponent of the draft and supported spending increases for education, health care and other social services, and reductions in military spending.

In the area of national security and foreign policy, Chisholm worked for the revocation of Internal Security Act of 1950.[35] She opposed the American involvement in the Vietnam War and the expansion of weapon developments. During the Jimmy Carter administration, she called for better treatment of Haitian refugees.

Chisholm's first marriage ended in divorce in February 1977. Later that year she married Arthur Hardwick, Jr., a former New York State Assemblyman whom Chisholm had known when they both served in that body and who was now a Buffalo liquor store owner. Chisholm had no children.

Hardwick was subsequently injured in an automobile accident; desiring to take care of him, and also dissatisfied with the course of liberal politics in the wake of the Reagan Revolution, she announced her retirement from Congress in 1982.

After leaving Congress, Chisholm made her home in Williamsville, New York. She resumed her career in education, being named to the Purington Chair at the all-women Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts. As such she was not a member of any particular department, but would be able to teach classes in a variety of areas; those previously holding the position included W. H. Auden, Bertrand Russell, and Arna Bontemps.

At Mount Holyoke, she taught politics and sociology from 1983 to 1987. She focused on undergraduate courses that covered politics as it involved women and race.Dean of faculty Joseph Ellis later said that Chisholm "contributed to the vitality of the College and gave the College a presence." In 1985 she was a visiting scholar at Spelman College. Hardwick died in 1986.

During those years, she continued to give speeches at colleges, by her own count visiting over 150 campuses since becoming nationally known. She told students to avoid polarization and intolerance: "If you don't accept others who are different, it means nothing that you've learned calculus."

Continuing to be involved politically, she traveled to visit different minority groups and urging them to become a strong force at the local level. In 1984 and 1988, she campaigned for Jesse Jackson for the presidential elections. In 1990, Chisholm, along with 15 other African-American women and men, formed the African-American Women for Reproductive Freedom.

Chisholm retired to Florida in 1991. In 1993, President Bill Clinton nominated her to be United States Ambassador to Jamaica, but she could not serve due to poor health and the nomination was withdrawn. In the same year she was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.

Chisholm died on January 1, 2005, in Ormond Beach near Daytona Beach, after suffering several strokes. She was buried in Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo, New York.

In February 2005, Shirley Chisholm '72: Unbought and Unbossed, a documentary film, aired on U.S public television. It chronicled Chisholm's 1972 bid for the Democratic presidential nomination. It was directed and produced by independent, African-American filmmaker Shola Lynch. The film was featured at the Sundance Film Festival in 2004. On April 9, 2006, the film was announced as a winner of a Peabody Award.

Renewed attention was paid to Chisholm during the 2008 Democratic presidential primaries, when Barack Obama and Hillary Rodham Clinton staged a historic battle where the victor would either be the first major party African-American nominee or female nominee. Observers pointed out that Chisholm's 1972 campaign had paved the way for both of them.

The Shirley Chisholm Center for Research on Women exists at Brooklyn College to promote research projects and programs on women and to preserve the legacy of Chisholm. The college's library also houses an archive called the Shirley Chisholm Project on Brooklyn Women's Activism.

Chisholm wrote two autobiographical books.

Chisholm was the keynote speaker at Hunter College's graduation in 1971. In 1974, Chisholm was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Laws degree by Aquinas College and was their commencement speaker. In 1975, Chisholm was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Laws degree by Smith College.

In 1993, she was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.

In 1996, she was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Laws Degree by Stetson University, in Deland, FL.(May 12, 1996)

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Shirley Chisholm on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

On January 31, 2014, the Shirley Chisholm Forever Stamp was issued. It is the 37th stamp in the Black Heritage series of U.S. stamps.

Once again

Amral posted:We had a long running page but lost it. This is what I can find from archives

This original thread goes back 14 years.

Amral, probably this article should be updated every February. ![]()

Mysteries of Canada, Source - https://www.mysteriesofcanada....ous-black-canadians/

One of the first Famous Black Canadians that comes to mind is Harry Jerome. Long before Ben Johnson or Donovan Bailey, Harry Jerome was Mr. Canada and the world’s fastest man and one of our best-known athletes despite an injury-prone career. Born in Prince Albert, Sask., and residing in Vancouver, he won a bronze medal at the 1964 Olympics, and gold at the 1966 Commonwealth Games. His first world record was a 10-second flat 100-metre sprint.

Harry Jerome Mr Canada

2. Portia White was born in the town of Truro, Nova Scotia. She went from singing in her father’s African Baptist church choir as a child to performing around the world as a concert singer. As a teacher in rural Halifax schools, Ms. White was able to realize her potential through support of Ladies’ Musical Clubs and the Nova Scotia Talent Trust. One of her last major appearances was at the 1964 opening of the Charlottetown’s Confederation Centre for the Arts, where Queen Elizabeth II was in attendance.

3. The real McCoy was a black Canadian, born to escaped Kentucky slaves in Colchester, Ont. in 1843. Despite having studied engineering in Scotland, on his return to Canada, Elijah McCoy was unable to find any job other than as a railway fireman. As a mechanic in the 1870s, he noticed that machines had to stop every time they needed oil. Mr. McCoy invented a device to oil machinery while it was working, and soon no engine or machine was complete until it had a McCoy Lubricator.

4. In 1857, William Hall became the first Black Canadians sailor as well as the first Famous Black Canadians to receive the Victoria Cross. Born in Horton Bluff, N.S., he joined the Royal Navy when only a teenager. He was also decorated for bravery during the Crimean War.

5. John Ware‘s saddle, spurs and gun can be seen at Alberta’s Dinosaur Park, remembering one of the best cowboys of the late 1800s. Born in Fort Worth, Texas, he helped set up the Bar U Ranch in the Northwest Territories, and his prowess at roping and trail breaking earned him a spot as a great cowboy.