https://www.kaieteurnewsonline...n-canadian-engineer/

Guyana’s Production Sharing Agreement (PSA) with ExxonMobil’s subsidiary, Esso Exploration and Production Guyana Limited (EEPGL), for the Stabroek Block has fielded major criticisms for a range of provisions, or the lack thereof, which are disastrous for Guyana.

Now, Darshanand Khusial has stated that a failure to define “market rate” as it is stated in the Contract could cost Guyana billions of US dollars. Here’s how:

As the PSA is currently structured, it allows the Operator to recover the loans it has taken to fund its activities in the Contract Area. It also allows the Operator to recover the interest incurred on those loans, with not a single cap on how much of that interest can be recovered.

Khusial has stated, “why Guyana would agree to pay interest on loans that the oil companies negotiated with their bankers is puzzling.”

But a more “egregious” flaw he pointed out is that Guyana has to pay the interest on these loans at a “market rate”.

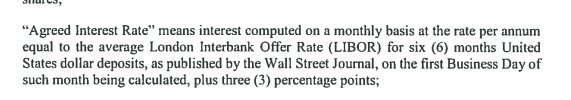

Interestingly, “Agreed Interest Rate” is clearly and precisely defined on page 3 of the Contract, but “Market Rate”, which is used in Annex C Section 3.1 of the Contract, titled “Costs Recoverable Without Further Approval of the Minister”, isn’t defined.

“Why would the oil companies want to avoid giving a precise meaning to ‘market rate’?” Khusial questioned.

He wrote, “Esso is a company with negative equity, as [pointed out] by [Attorney-at-Law and Accountant] Chris Ram in 2018.”

Khusial determined that, now, as Esso still hasn’t produced oil, its negative equity would be even higher.

He provided that, “Negative equity means if you liquidate all your assets you still won’t be able to pay-off your current loans.”

He pointed out that with ExxonMobil’s exemplary credit rating, which allows it to take out loans at lower costs than its peers, the market rate charged may be low. But that won’t apply to Guyana, since it signed the PSA with Exxon’s subsidiary, Esso, not Exxon itself.

The market interest rate Guyana would be paying would be on Esso’s loans, not ExxonMobil’s, said Khusial.

He wrote, “Liza Phase 1 has a projected gross capital cost of US$3.7 billion and Liza Phase 2 has a gross capital cost of US$6 billion – with total combined production estimated at 1.05 billion barrels of oil. One should observe that going from 450 million barrels in Phase 1 to 600 million barrels in Phase 2 increased the capital cost per barrel by 20%. However, one would expect, given the lessons learned from the first project, the cost per barrel for the second project should be less than the first. Instead, the difference in cost adds up to an additional US$1 billion!”

Khusial determined that the capital cost up to the current estimated reserves in the Stabroek Block of 6B barrels would be US$55B, and that the interest would be three percent, had the agreement been signed with ExxonMobil, using ‘Agreed Interest Rate’, as it is defined in the PSA. He calculated that that would grant ExxonMobil an extra US$1.7B. That US$1.7B would apply for ExxonMobil, which is considered “low risk”.

“But Esso… a company registered in Bahamas and with negative equity… would be classified as high risk. If one checks the market rates of bonds issued by Exxon, you can find the yields of around 2%. But what rate would Esso — a company with negative net worth — be charged for its loan?”

“Earlier this year, it was reported by CNN that because of the plunge in oil prices investors have lost their appetite for risky companies.”

Khusial said that it may be highly unlikely that Esso would even be able to receive a loan in the market.

“This is where Exxon can leverage its low borrowing rate to its advantage. In a typical scenario with the big oil companies, Exxon can loan Esso the money. But what would be “market rate” charged to Esso?”

Khusial pointed out small, risky companies, like California Resources and Weatherford International, which currently pay market rates of 30 and 18 percent respectively.

He calculated that a 15 percent difference in the market rate could mean Guyana forks up an extra US$8B, and that a 30 percent difference would cost the country an extra US$16B.

“Now, that sleight of hand not to use the ‘Agreed Interest Rate’ in a section titled “Costs Recoverable Without Further Approval of the Minister“ – doesn’t seem accidental but carefully planned by the oil companies.”