Here's the story behind Black History Month — and why it's celebrated in February

[[[Quote]]]

Why February was chosen as Black History Month

February was chosen primarily because the second week of the month coincides with the birthdays of both Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. Lincoln was influential in the emancipation of slaves, and Douglass, a former slave, was a prominent leader in the abolitionist movement, which fought to end slavery.

[[[Unquote]]]

At the March on Washington on Aug. 28, 1963, African Americans carry placards demanding equal rights, integrated schools, decent housing and an end to bias. -- Warren K Leffler/Universal History Archive/Getty Images

At the March on Washington on Aug. 28, 1963, African Americans carry placards demanding equal rights, integrated schools, decent housing and an end to bias. -- Warren K Leffler/Universal History Archive/Getty Images

Every February, the U.S. honors the contributions and sacrifices of African Americans who have helped shape the nation. Black History Month celebrates the rich cultural heritage, triumphs and adversities that are an indelible part of our country's history.

This year's theme, Black Health and Wellness, pays homage to medical scholars and health care providers. The theme is especially timely as we enter the third year of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has disproportionately affected minority communities and placed unique burdens on Black health care professionals.

"There is no American history without African American history," said Sara Clarke Kaplan, executive director of the Antiracist Research & Policy Center at American University in Washington, D.C. The Black experience, she said, is embedded in "everything we think of as 'American history.' "

First, there was Negro History Week

Critics have long argued that Black history should be taught and celebrated year-round, not just during one month each year.

It was Carter G. Woodson, the "father of Black history," who first set out in 1926 to designate a time to promote and educate people about Black history and culture, according to W. Marvin Dulaney. He is a historian and the president of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH).

Woodson envisioned a weeklong celebration to encourage the coordinated teaching of Black history in public schools. He designated the second week of February as Negro History Week and galvanized fellow historians through the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, which he founded in 1915. (ASNLH later became ASALH.)

The idea wasn't to place limitations but really to focus and broaden the nation's consciousness.

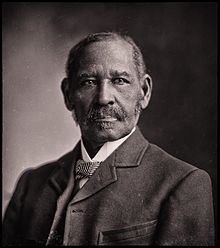

Carter G. Woodson (1875-1950) was an American historian, a scholar and the founder of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. Woodson was instrumental in launching Negro History Week in 1926. -- Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

"Woodson's goal from the very beginning was to make the celebration of Black history in the field of history a 'serious area of study,' " said Albert Broussard, a professor of Afro-American history at Texas A&M University.

The idea eventually grew in acceptance, and by the late 1960s, Negro History Week had evolved into what is now known as Black History Month. Protests around racial injustice, inequality and anti-imperialism that were occurring in many parts of the U.S. were pivotal to the change.

Colleges and universities also began to hold commemorations, with Kent State University being one of the first, according to Kaplan.

Fifty years after the first celebrations, President Gerald R. Ford officially recognized Black History Month during the country's 1976 bicentennial. Ford called upon Americans to "seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of Black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history," History.com reports.

Why February was chosen as Black History Month

February was chosen primarily because the second week of the month coincides with the birthdays of both Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. Lincoln was influential in the emancipation of slaves, and Douglass, a former slave, was a prominent leader in the abolitionist movement, which fought to end slavery.

Lincoln and Douglass were each born in the second week of February, so it was traditionally a time when African Americans would hold celebrations in honor of emancipation, Kaplan said. (Douglass' exact date of birth wasn't recorded, but he came to celebrate it on Feb. 14.)

Thus, Woodson created Negro History Week around the two birthdays as a way of "commemorating the black past," according to ASALH.

Forty years after Ford formally recognized Black History Month, it was Barack Obama, the nation's first Black president, who delivered a message of his own from the White House, a place built by slaves.

President Barack Obama and first lady Michelle Obama host the annual reception for Black History Month at the White House on Feb. 18, 2016.

"Black History Month shouldn't be treated as though it is somehow separate from our collective American history or somehow just boiled down to a compilation of greatest hits from the March on Washington or from some of our sports heroes," Obama said.

"It's about the lived, shared experience of all African Americans, high and low, famous and obscure, and how those experiences have shaped and challenged and ultimately strengthened America," he continued.

(Canada also commemorates Black History Month in February, while the U.K. and Ireland celebrate it in October.)

There's a new theme every year

ASALH designates a new theme for Black History Month each year, in keeping with the practice Woodson established for Negro History Week.

This year's Black Health and Wellness theme is particularly appropriate, Dulaney said, as the U.S. continues to fight the coronavirus pandemic.

"As [Black people], we have terrible health outcomes, and even the coronavirus has been affecting us disproportionately in terms of those of us who are catching it," Dulaney said.

"There's never been a time where Black people and others should not celebrate Black history," Broussard said. "Given the current racial climate, the racial reckoning that began in wake of George Floyd's murder ... this is an opportunity to learn."

Claudette Colvin in 2020 -- Photo: Craig Barritt/Getty Images for Tory Burch Foundation

Claudette Colvin in 2020 -- Photo: Craig Barritt/Getty Images for Tory Burch Foundation

Lincoln Alexander was Canada’s first black member of Parliament, but those who met him also remember the late politician as a proud Hamiltonian, a music fan and a proponent of education. Here, Alexander rides in a 1986 parade as Ontario’s lieutenant-governor. (Gary Hershorn/Reuters)

Lincoln Alexander was Canada’s first black member of Parliament, but those who met him also remember the late politician as a proud Hamiltonian, a music fan and a proponent of education. Here, Alexander rides in a 1986 parade as Ontario’s lieutenant-governor. (Gary Hershorn/Reuters)

Toronto university student Safia Thompson says Alexander helped inspire her to pursue law school. (Submitted by Safia Thompson)

Toronto university student Safia Thompson says Alexander helped inspire her to pursue law school. (Submitted by Safia Thompson)

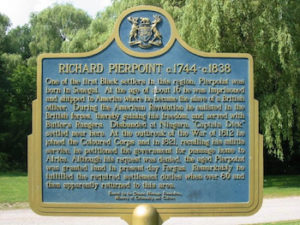

Source -

Source -

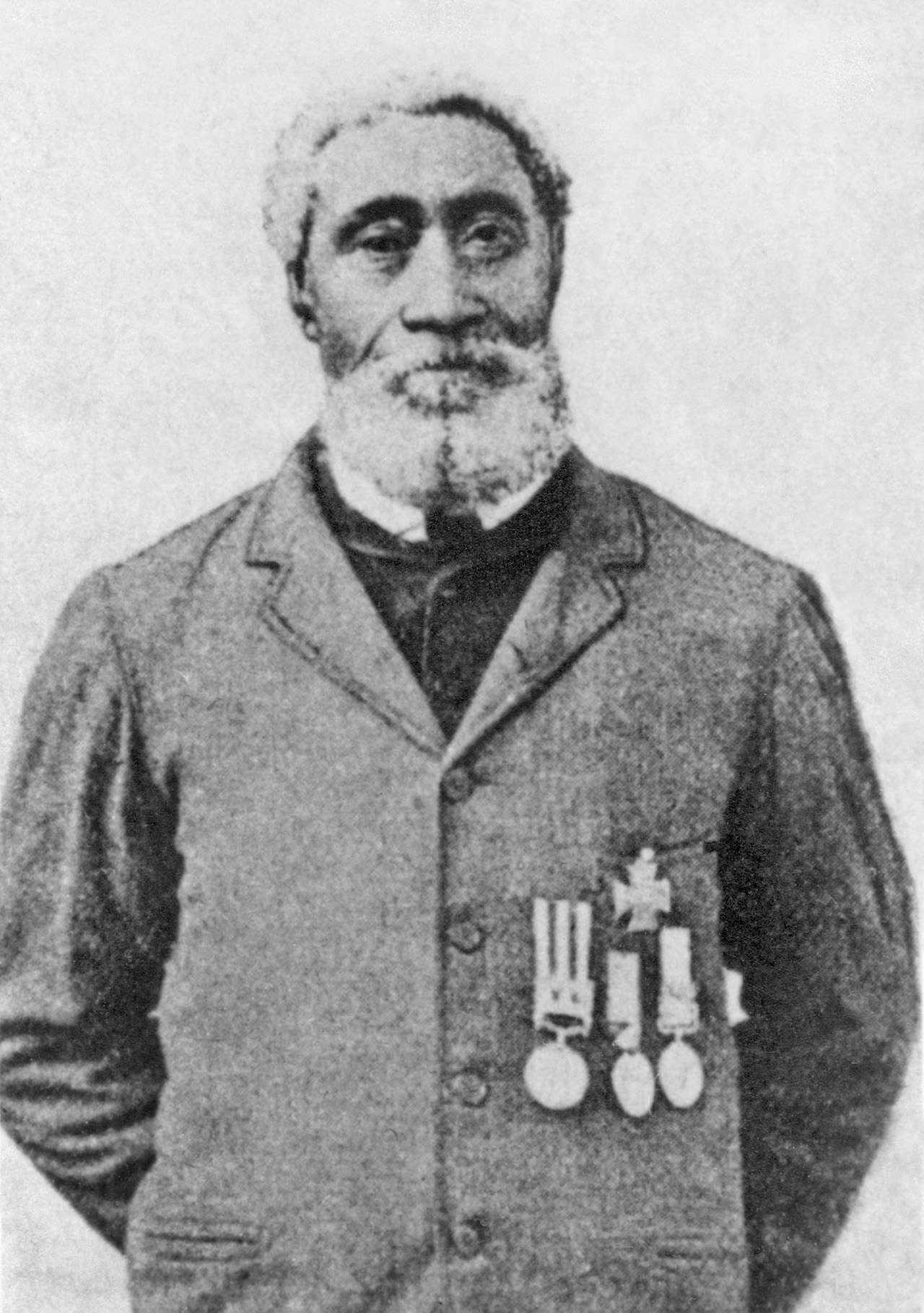

DND -- Petty Officer (PO) William Hall VC

DND -- Petty Officer (PO) William Hall VC

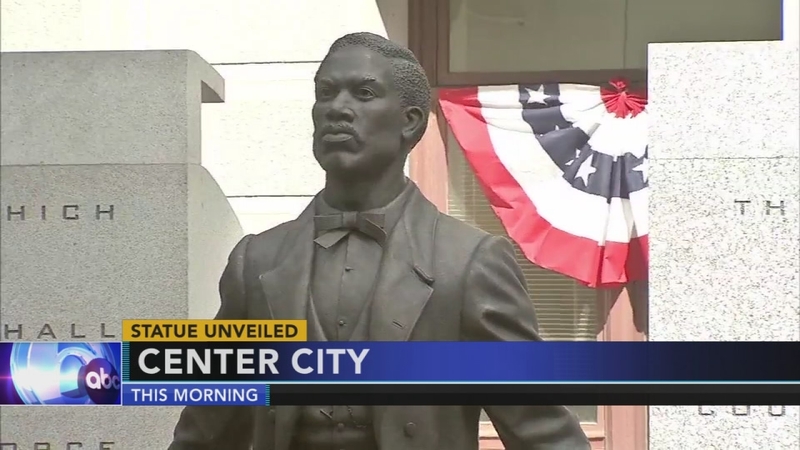

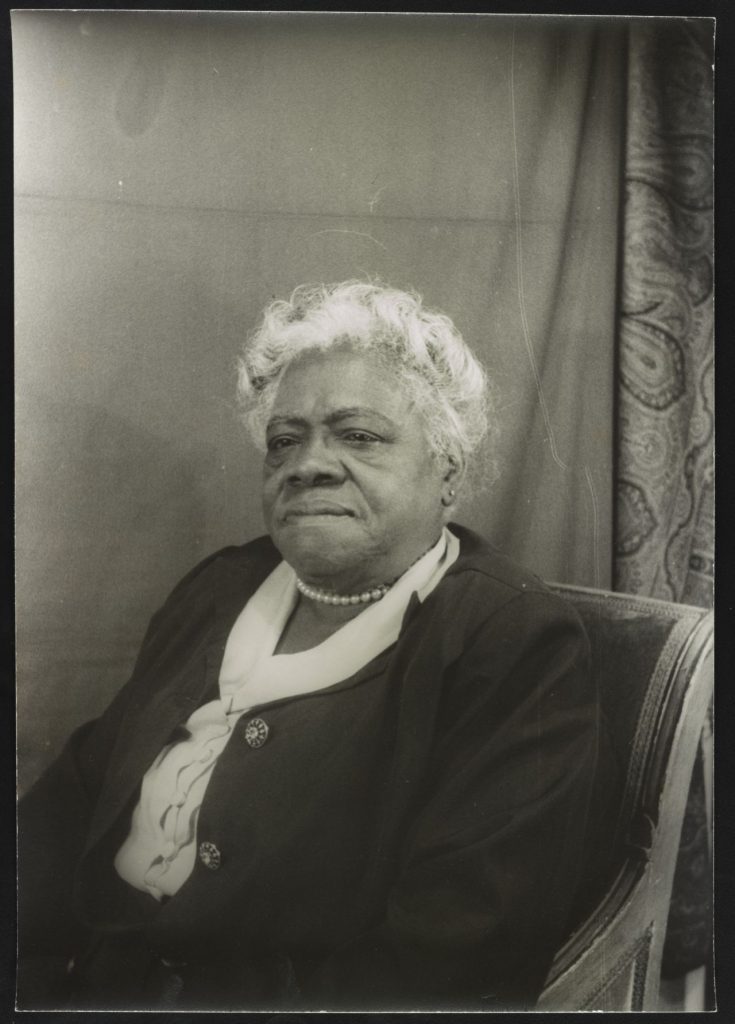

Portrait of Mary McLeod Bethune

Portrait of Mary McLeod Bethune Mary McLeod Bethune Memorial, Washington, D.C.

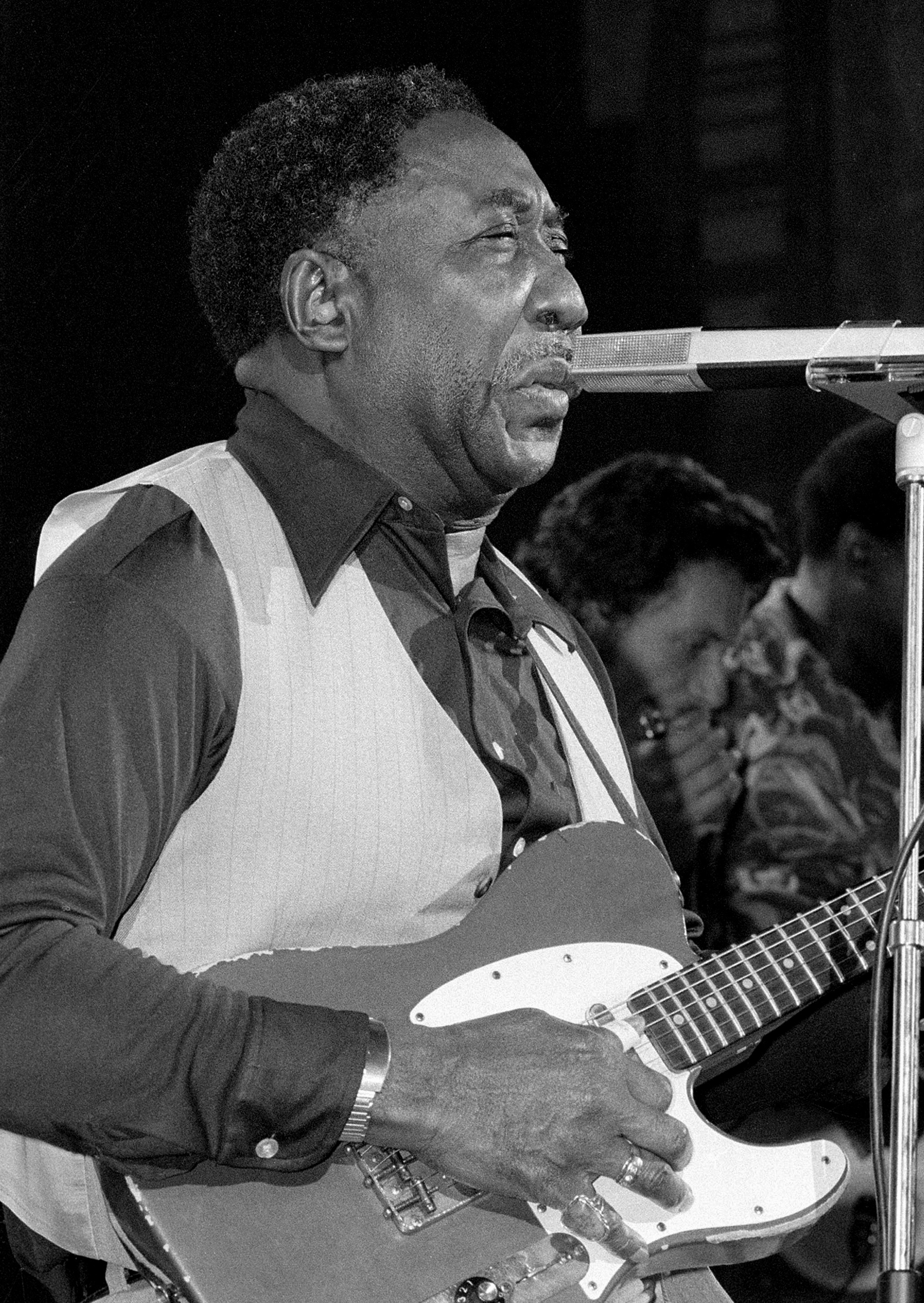

Mary McLeod Bethune Memorial, Washington, D.C. Frances E.W. Harper

Frances E.W. Harper