Kenyan Mau Mau promised payout as UK expresses regret over abuse

William Hague to announce payments of £2,600 each to some 5,000 survivors of UK prison camps set up during 1950s conflict

The British government will on Thursday agree an historic compensation payment to victims of one of the darkest episodes of the country's imperial past and express its "sincere regret" for the torture inflicted upon thousands of people imprisoned during Kenya's Mau Mau insurgency.

In a statement to MPs, William Hague, foreign secretary, is expected to announce payments of £2,600 each to more than 5,000 survivors of the vast network of prison camps that the British authorities established across its colony during the bloody 1950s conflict: a total of about £13.9m.

After weeks of negotiations with lawyers representing three elderly former prisoners who brought a series of test cases in the high court in London, the government has agreed also to fund the construction of a memorial in Nairobi to Kenya's victims of colonial-era torture.

The settlement, predicted by the Guardian last month, is a historically significant moment, representing the first major compensation payment arising from official crimes committed as Britain withdrew from its empire. It is also the first governmental acknowledgment that such serious crimes were committed at that time.

It could also pave the way for further claims from around Britain's former empire. Former Eoka guerrillas who were imprisoned and allegedly mistreated by the British during counter-insurgency operations in 1950s Cyprus are considering legal action against the British government, for example, while government officials in Guyana, where British troops detained and interrogated large numbers of people during the 60s, have also been examining details of the case.

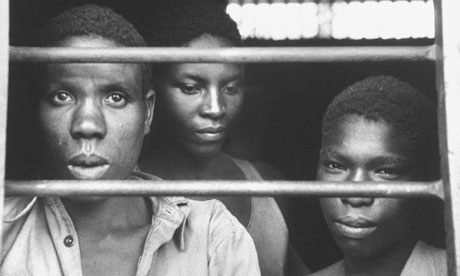

Captured Mau Mau fighters in Kenya awaiting trial in 1954. Photograph: George Rodger/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

Captured Mau Mau fighters in Kenya awaiting trial in 1954. Photograph: George Rodger/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

The Foreign Office (FCO) declined to comment on Wednesday, although it had issued a statement when it emerged that talks were under way last month, in which it said: "We believe there should be a debate about the past. It is an enduring feature of our democracy that we are willing to learn from our history."

Martyn Day, the elderly Kenyans' lawyer, said: "We are looking forward to the statement by William Hague in the House of Commons. We very much hope that this will be the final resolution of this legal battle that has been ongoing for so many years."

Although the government is poised to express regret, the settlement was preceded by four years of dogged courtroom battles during which government lawyers repeatedly resisted the claims.

During the first round of hearings, the government argued that the claimants should not be suing the British government, but the Kenyan authorities, which had inherited London's legal responsibilities on independence, under the principle of states succession.

During the second round, the British government acknowledged that the allegations of murder and torture were true, but argued that too much time had elapsed for there to be a fair trial.

That position was rejected by the high court in October, with Mr Justice McCombe ruling that a fair trial was possible. "The documentation is voluminous," he said. "The governments and military commanders seem to have been meticulous record keepers."

A round-up of Mau Mau suspects being led away for questioning by police after being captured in a raid in the Great Rift Valley. Photograph: Popperfoto/Getty

A round-up of Mau Mau suspects being led away for questioning by police after being captured in a raid in the Great Rift Valley. Photograph: Popperfoto/GettyThe turning point came when a number of historians, who gave evidence as expert witnesses, realised the government's disclosure of documentation was incomplete. This in turn led to the government admitting to the existence of an enormous secret archive of more than 8,000 files from 37 former colonies.

During an eight-year conflict in which Britain sought to restore order on its prized African possession, amid a vicious insurgency fuelled by land shortages in its central highlands, an estimated 90,000 people were killed or injured. More than 100,000 people were detained, many of them Kikuyu, Kenya's largest ethnic group. Although some were Mau Mau guerillas, many were victims of collective punishment that colonial authorities imposed on large areas of the country.

Thousands suffered beatings and sexual assaults during "screenings" intended to extract information about the Mau Mau threat. Later, prisoners suffered even worse mistreatment in an attempt to force them to renounce their allegiance to the insurgency and to obey commands. Significant numbers were murdered; official accounts describe some prisoners being roasted alive.

One of the high-court claimants, Wambugu Wa Nyingi described how he was detained in 1952, held for nine years, much of the time in manacles, and beaten unconscious during a particularly notorious massacre at a camp at Hola in which 11 men died.

Among the detainees who suffered severe mistreatment was Hussein Onyango Obama, the grandfather of Barack Obama. According to his widow, British soldiers forced pins into his fingernails and buttocks and squeezed his testicles between metal rods. Two of the original five claimants who brought the test case against the British government were castrated.

Once the government admitted the existence of the vast archive of papers, many of which corroborated the claimants' accounts of abuse, it became clear that thousands more from across the former empire had also been stored secretly for decades at a secure government research centre at Hanslope Park in Buckinghamshire, north of London.

Among the papers that had been withheld from the courts – and from the National Archive at Kew, south west of London – was a memo from Kenya's attorney general, Eric Griffith-Jones, who had described the mistreatment of the detainees as "distressingly reminiscent of conditions in Nazi Germany or Communist Russia". Despite his concerns, he agreed to draft legislation that sanctioned beatings, as long as the abuse was kept secret. "If we are going to sin," he wrote, "we must sin quietly."

After the disclosure of the existence of the Hanslope Park archive, Hague commissioned Anthony Cary, the former British high commissioner to Canada, to carry out an inquiry to establish why its contents had not been passed to the National Archive.

Cary later reported that "a canard that was widely shared and passed down" included the explanation that the FCO was holding the archive on behalf of a private company that had suffered a fire. As a result, it was never assessed for declassification, as the law required, and placed beyond reach of the Freedom of Information Act.

Hague subsequently told MPs the contents would finally be transferred to Kew. "I believe that it is the right thing to do for the information in these files now to be properly examined and recorded and made available to the public through the National Archives," he said. "It is my intention to release every part of every paper of interest subject only to legal exemptions."

In April it emerged that many of the papers were still being withheld by the FCO, using a legal exemption contained within a catch-all clause within the 1958 Public Records Act, the law that the department had breached by maintaining the secret archive. The reason for the continuing secrecy is itself a secret, however, as the FCO refuses to explain why some files are being withheld.