The former president's death, whenever it comes, could have a profound impact on the nation's identity

David Smith in Johannesburg

The Observer, Sunday 26 February 2012

Source - Guardian, UK

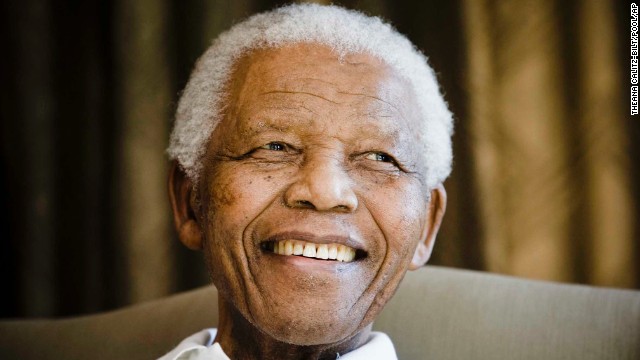

Nelson Mandela in 2007. Photograph: Peter Dejong/AP

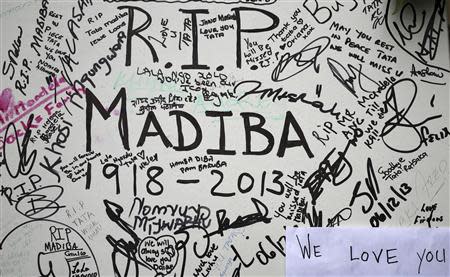

It is the day South Africans dread more than any other, and it is not a question of if but when. The death of Nelson Mandela will shake the nation to its core; the fact that death in old age does not fit the proper definition of "tragedy" will not console the millions who grew up with him as a constant, consoling presence.

It is the day South Africans dread more than any other, and it is not a question of if but when. The death of Nelson Mandela will shake the nation to its core; the fact that death in old age does not fit the proper definition of "tragedy" will not console the millions who grew up with him as a constant, consoling presence."It's like watching one's grandfather fade away," was how Heidi Holland, the South African-based journalist, put it recently. After Mandela's previous health scare last year, newspaper editor Nic Dawes wrote of a "country huddled as if in a national waiting room".

He added: "What South Africans feel for Madiba is not simply affection or respect. Even love may not be a strong enough word. His presence is part of the structure of our national being. We worry that we may not be quite ourselves without him."

But Mandela's death will also be an almost unprecedented global event, with every living US president, the British prime minister and other world leaders expected to attend his funeral. International broadcasters have drawn up so-called "M-plans", staking out locations, pre-booking hotels and transport, and signing up pundits for the occasion.

Therein lies discord. The collision between grief and the media's desire to be first and best with its coverage has already produced some ugly clashes. Some South Africans complain that it is vulture-like and "un-African" to discuss the death of someone still alive, while journalists insist they have to do their jobs and that viewers and readers will demand coverage over those historic few days.

Now that he is 93, every rumour about Mandela's health triggers panic, and a single reckless tweet can send officials and media into meltdown.

When he was hospitalised just over a year ago, TV crews, reporters and photographers camped outside and the Twitter rumour mill ran wild – not the social network's finest hour. The slow response of officials left an information vacuum, leading to weeks of recriminations. Then last December it emerged that Associated Press and Reuters had installed CCTV cameras at a house opposite Mandela's in Qunu, Eastern Cape province. A public outcry and police investigation followed. Last week the owner of the house, chieftainess Nokwanele Balizulu, declined to comment.

Again, on Saturday, there was trouble when a photographer was forced into a military police van for taking a picture of a hospital building thought to contain Mandela. But unlike the last hospitalisation, this time there appears to be a concerted effort by the government, the Nelson Mandela Foundation and the Mandela family to co-ordinate the flow of information.

Ndileka Mandela, the former president's granddaughter, told the Observer: "I need to respect the agreement between the government and the family that only the presidency will release details about his health. Last year it became a complete media fracas. We want to avoid all that again."

When the inevitable happens, however, there are fears that divisions within the family will be exposed. Nelson Mandela's grandson and heir apparent, Mandla Mandela, has become a divisive figure. There are reports that police want to charge him with bigamy and that he may be forced to reveal in court whether he has sold the TV rights to his grandfather's funeral. He also caused further upset when he ordered three of Nelson Mandela's children to be exhumed from Qunu and reburied 24 miles away in the hamlet where he is a chief, Mvezo. Nelson Mandela was born in Mvezo and many suspect Mandla will seek to have him buried there, alongside a money-spinning museum.

Nonkumbulo Habe, 44, a teacher in Qunu who is related to Nelson Mandela, said: "Mandla is a silly child. He is causing divisions in the family."

Mandla is the grandson of Nelson Mandela's late first wife, Evelyn Mase. His plans could well clash with those of Mandela's second wife, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, and her formidable daughters, as well as his current wife, Graça Machel, herself a strong personality. But for many, the overriding emotion will be grief. Noluzile Gamakhulu, 81, who lives in Qunu and has known Mandela all her life, said: "If he passes on, we will all really, really cry."

Publishing juggernaut ... Nelson Mandela, whose autobiography has so far sold 6m copies, salutes supporters in 1994. Photograph: David Brauchli/AP

Publishing juggernaut ... Nelson Mandela, whose autobiography has so far sold 6m copies, salutes supporters in 1994. Photograph: David Brauchli/AP