On Harriet Tubman’s Final Escape Mission

A November Snowstorm and a Last-Minute Change of Plans

Harriet’s network of antislavery agitators stationed across the country was extensive, but she also developed a vital relationship with one of the most infamous abolitionists of the era. Harriet’s bravery and knowledge of the Maryland terrain caught the attention of a man who was willing to stop at nothing to end the trade of human beings. John Brown would eventually lose his life in the fight to end slavery, but before that day came, he met and became friendly with the woman he would call “General.”

Brown was born in Connecticut but spent a good deal of his life on the Ohio frontier, struggling to raise a family and move beyond poverty’s reach. By the mid-1830s, Brown was disillusioned with life but captivated by the abolitionist crusade. He became a radical antislavery agitator with a fervent belief that slavery needed to end immediately and by any means necessary. Unlike other abolitionists who believed in slow and nonviolent protest, John Brown was prepared to fight, maim, and kill those who stood in the way of his mission. In 1856, he moved to Kansas and joined the sectional battle to make Kansas a free state, using violence as a weapon against proslavery settlers. The guerilla warfare tactics he employed in this conflict were as violent as slavery itself. John Brown earned a reputation—he was not one to be dismissed.

With each passing year, Brown became more and more dissatisfied with the slow pace of slavery’s demise. Frustrated and furious, he began to piece together a plan. He would build an army of abolitionists who would invade the South and convince enslaved men and women they met along the way to join their ranks. It would be a revolution—a revolution that would install a new government with a new constitution. Brown spent several weeks in Rochester, New York, at the home of Frederick Douglass, talking and thinking about his constitution and his future plans. The renegade abolitionist wanted the powerful orator and famous antislavery agitator to join his insurrection, but Frederick Douglass thought Brown’s plans were foolish and would never successfully upend the power of the United States military. There was, however, another antislavery warrior that Brown wanted desperately to meet and recruit. He had heard about a woman who was known for her actions, not words, just the kind of person Brown needed in his army. In April of 1858, John Brown finally met the famous Harriet Tubman.

The first meeting between Brown and Tubman pumped new energy into his plan for insurrection. Because many abolitionists were uncomfortable with the idea of violence, Brown received tepid support from headliner activists. Most of them had never experienced slavery’s cruelty and couldn’t imagine joining or even supporting what appeared to be a fool’s errand that would end in bloodshed. But Tubman was different. Like her associate Frederick Douglass, she knew slavery’s violence all too well and had also grown tired of waiting for a peaceful end to it. By the late 1850s, most black people, especially fugitives, knew that slavery would never end without a fight. Only a war would end human bondage, and Harriet decided to throw her support behind the man who was not afraid to speak of the inevitable.

It must have been refreshing to finally meet someone who had a concrete plan to end slavery. The trips back and forth from Maryland to Philadelphia and then Canada grew more difficult with each passing year, and even though she rescued nearly 70 people from slavery, Harriet understood this was a drop in the bucket. There were more than four million enslaved people across the nation, and she knew that one or two trips a year to the Eastern Shore only helped her family and friends. John Brown presented a plan that was risky and unlikely to succeed, but at least it was action, and this spoke to Harriet.

There was one more dire mission to complete; she had to return to Maryland and try once again to rescue her sister Rachel and her two children, Angerine and Ben.

Armed rebellion against the United States would be almost impossible to plan, but Harriet’s knowledge of allies and friends throughout Maryland could lend support to an attack in neighboring Virginia. More important, she agreed to use her influence among her friends in Canada to try to convince able-bodied men to join in Brown’s future attack. If anyone could convince black men to leave the safety of Canada and engage in armed combat, it was Harriet. She had just as much to lose as the men she tried to recruit.

Brown paid Harriet $25 in gold to support her recruitment efforts throughout the spring and summer. She traveled to Auburn, New York, in the fall to check in with her family, and then to Boston during the winter where, once again, she met up with John Brown. Harriet’s support for Brown grew stronger, and she used her energy to raise funds for him during her speaking engagements across New England. During a Fourth of July presentation, Harriet kept her audience spellbound and collected close to $40—equal to $1,200 today—for her new comrade. As John Brown traveled down to Harpers Ferry, Virginia, where he planned to start his revolution, Harriet continued on her speaking tour, raising awareness and waiting for word about armed insurrection.

On August 19, 1859, Brown made his last appeal to his friend Frederick Douglass, asking for his support in an attack against the arsenal at Harpers Ferry. The two met in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, where he assured Douglass that enslaved men and women would throw down their tools and join in the rebellion once it began. Douglass disagreed and declined the invitation to fight, believing the strategy would be a certain failure.

Douglass was out, but Harriet remained a loyal supporter of Brown. During one of their earlier meetings, Harriet suggested that Brown begin the insurrection on Independence Day, an act that would send a symbolic message about freedom and democracy. But Brown was delayed, and revised details about the planned rebellion never found their way to Harriet’s ears. When John Brown began his attack on October 16, 1859 at Harpers Ferry, he had only a small group of volunteer soldiers prepared to fight against the United States.

Harriet was in New York at the time, and unaware that the battle had begun. Still, she had a bad feeling, perhaps a premonition, that something was terribly wrong. When Harriet eventually learned about the poor planning, the lack of support, and the bloody defeat that came so fast and furious, her intuition was confirmed.

By December 2, John Brown stood on the gallows, completely unapologetic about his actions, prepared to meet his maker. Harriet lost another ally to the power that supported slavery. If it wasn’t clear before, Harriet knew that war was the only thing that could extinguish slavery’s fire, but until that moment came, she vowed to chip away at the evil that kept so many in chains.

For nearly a decade, Harriet avoided capture as she went back into the lion’s den to rescue friends and family. She never lost a fugitive to illness or capture, an accomplishment that reminded Harriet of her own strength and of God’s power. Now in her late thirties, Harriet’s body began to show the signs of ruthless wear and tear, making recovery from illness more and more difficult and prolonged. In addition to her rescue work, she had other stressors. With her new home, she carried a large financial responsibility that required her to tour across New England speaking out against slavery, work that was relentless and never secure.

With the federal crackdown following the raid on Harpers Ferry, many of Harriet’s friends and family members advised her to return to Canada and to move about New England and upstate New York only when necessary and with the greatest of caution. Headstrong, Harriet didn’t listen. There was one more dire mission to complete; she had to return to Maryland and try once again to rescue her sister Rachel and her two children, Angerine and Ben. With the exception of these three people, Harriet had pulled her entire immediate family that remained in Maryland away from slavery’s hold. The thought of her sister languishing on the farm without any family support must have been torturous, not only for Harriet but also for her parents and brothers. Harriet was compelled to make one last trip to Dorchester County to rescue the last of her family members.

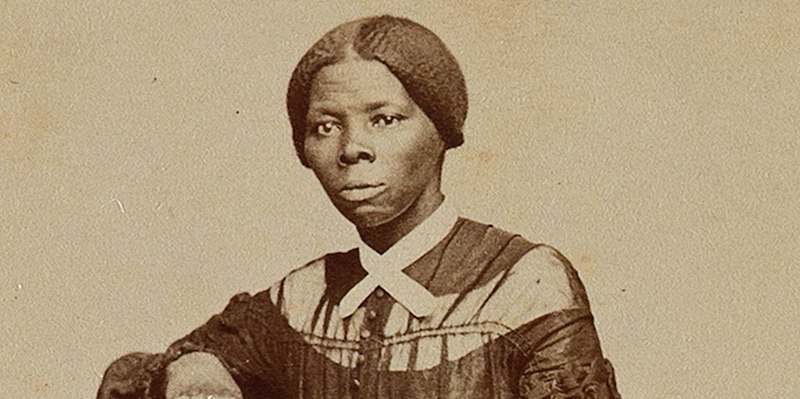

Just as she had done in the past, Harriet began the work of collecting funds for what was certain to be a dangerous trip. Dangerous because although eleven years had passed since she first escaped from Maryland, there was still a bounty on her head ranging upward of $12,000. Also, it was increasingly difficult for Harriet to keep a low profile; she was now a famous woman among antislavery circles, and her notoriety was a liability. On occasion, she would use pseudonyms, and the most famous abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, referred to her simply as a “colored woman of the name Moses.” But even these precautions were not fail-safe. Nonetheless, throughout the summer of 1860, she continued with speaking engagements across New England, collaborating with antislavery societies and abolitionists.

Despite her intense efforts, by the end of the summer, Harriet realized that she was still too short on cash to fund this last rescue and reached out to her friend and famed abolitionist Wendell Phillips. She asked him to make good on an earlier promise to assist her and to send money to a mutual friend in Philadelphia who would make certain it would find its way to Harriet. We don’t know if she ever received the money.

With or without the necessary funding, she would press forward. Political events in the country left her no choice. As autumn of 1860 approached, the axis of the nation appeared to shift during a messy presidential election season and the South’s mounting and heated response to Lincoln’s candidacy.

Harriet quietly slipped into Dorchester County, Maryland, to rescue her loved ones. She knew this might be the last opportunity to free her remaining family members from bondage before the nation split in two. With a deep sense of urgency, Harriet stuck to the byways and the roads that she knew by heart and arrived safely on the Eastern Shore. When she arrived, her heart almost shattered. Shortly before Harriet reached the Eastern Shore, Rachel died, leaving her children separated on different farms without a parent. The details regarding Rachel’s death are unknown, but the fact that the logistics didn’t come together in time to save her sister must have been a wound Harriet lived with for the rest of her days. Too late to help Rachel, she now turned her attention to Angerine and Ben and to devising a rescue plan for the children.

Her last escape mission left Harriet exhausted and in dire need of recuperation.

When the time came, Harriet went to an agreed upon location to meet the children. She waited and waited for them, and even spent the night in the woods, constantly surveying her surroundings, praying to see the shadows of the two remaining family members. A November snowstorm blanketed the Eastern Shore of Maryland that night, leaving Harriet alone and in the cold. She took shelter behind a tree, but still the blinding snow and raging wind pummeled her small frame. Warrior that she was, she ignored the bone-chilling temperatures and the accumulating snow. But when morning came, Angerine and Ben were nowhere in sight.

Harriet knew that slave-patrollers would soon resume their work. She had to leave the children behind. This, one of her few failures, could be attributed to lack of funds. Whether she was short of enough money to convince an accomplice to assist her, or to pay a watchful overseer to momentarily turn his back, or reasons we cannot fathom, the lack of money proved to be an insurmountable obstacle. True to form, she made certain that her trip was not in vain by whisking away a small group of runaways, including the Ennals family. They reached Delaware by the first of December, and while it took a bit more time than usual, they finally arrived in Canada by the end of the month. The runaways would celebrate New Year’s Day of 1861 as free people but in Harriet’s eyes, the mission was a failure.

Her last escape mission left Harriet exhausted and in dire need of recuperation. She traveled back to upstate New York to rest and tend to her frost-bitten feet, but her stay was brief as slave-catchers were spotted in and around the Auburn area. Their presence was a reminder of the intense sectarian crisis that had spun out of control and fractured the nation. While Harriet was busy on her last trip to Maryland, Abraham Lincoln was elected president of the United States, an event that prompted a furious response from Southern states. The Kentucky-born lawyer won the election of 1860 with only 40 percent of the popular vote, sending Southern Democrats into a tailspin. Even though the Supreme Court had ruled in their favor by protecting slavery, Southern states saw Lincoln’s victory as a threat to their existence and immediately began to discuss plans for secession.

Just five short weeks after Lincoln’s election, the state of South Carolina seceded from the Union. It was quickly joined by six other states in the black belt of slave country. Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Florida, and Texas would shoulder up with South Carolina, forming the Confederate States of America, a new country that would continue the tradition of Southern life and custom without the interference of Northern imposition. Eventually, Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina would join this new confederacy.

During the spring of 1861, Harriet continued giving antislavery talks and attending abolitionist meetings in New England. The funds she collected from her events went to support the fugitive community in Canada and her family, but resources were harder than ever to come by as the nation prepared for armed combat. Harriet formalized her support for her runaway friends by organizing the Fugitive Aid Society of St. Catharines. Its goal was to offer financial support to fugitives who found their way to Canada. Her years on the antislavery circuit must have convinced Harriet that the best way to cultivate donors and supporters was to create a stable and staffed organization. The Fugitive Aid Society was run by Harriet’s trusted family and friends, most of whom had fled from Delaware and Maryland. Their leadership was a symbol of the power and promise of formerly enslaved people.