Life on plantation De Kinderen

Pandit recounts his childhood days, changes in Indian culture

IN 1948, a week before giving birth, a woman was lending a hand to men who were bundling and fetching sugar cane on Plantation De Kinderen.

Though some may say it might have been a choice to work under those conditions during a post-indentureship era (1838-1917), the child who the woman gave birth to, Ramdular Singh, recalled that it might have been a different case since it was not the first time the nine-month period went by with her on the field.

Singh, now 70 years old, said his mother who worked on the plantation for over 50 years gave birth to him and four girls but, during every pregnancy she was out in the fields, working to maintain a living.

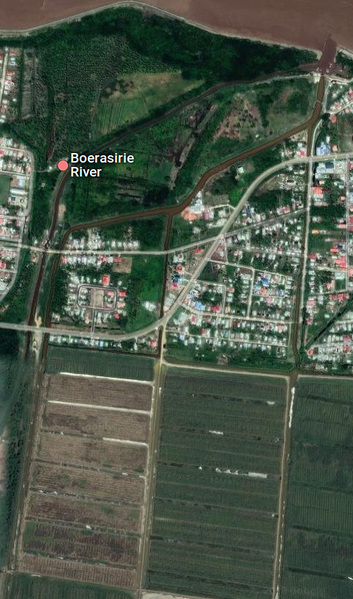

From the wet, muddy fields his mother and father would have to face more dirt on their way home since all the roads were basically mud.

He recalled how the place would be flooded every time it rained but, his parents would still have to go to work and he would have to make his way to school.

Since Guyana had not gained Independence from Great Britain as yet, colonisers were still in charge of the affairs and operations of the economy.

“Whites lived in an exclusive area, in European-style houses while my family lived in a house with mud walls and patched floors; from the stories that I heard, they were the masters although it was called an indentureship system… in my view it was a new type of slavery although East Indians had signed a contract,” said Singh, adding that even in his childhood days, the post-indentureship life was not very different.

A DAY’S WORK

Sugar workers, both men and women had to work from 06:00hrs to 19:0hrs from Monday to Saturday. It was quite similar to the days when the East Indians were initially brought to British Guiana to work as indentured labourers.

Although there were some differences such as the opportunity to attend a school and move away from the field life, only boys benefitted because girls were affected by the social pressures.

Instead of being sent to school, the girls had to get married at a young age. Singh said the only option the girls had was to learn how to sew for one year before getting married.

CULTURAL PRESSURES

In his family, because they were poor, his parents and four sisters worked in the fields to send him to school.

“As soon as my sisters turned teenagers, the pressure was on my parents because everyone was looking to see when they would be married off,” said Singh.

With no other option back then, the family chose to concentrate on educating him. He also had to face the criticisms from other people in his community because prior to 1940, Indians hardly had a desire to send their children to school.

While the Africans saw the importance of education and were able to get administrative positions, the Indians were skeptical because there was the common rule that persons would have to convert to Christianity before being able to work in the civil service or become a teacher.

Indians were predominantly Hindus and Muslims, so the fear of having to convert to another religion stopped them from taking certain opportunities.

Instead of taking the decision to send them to Catholic school, many people from Singh’s community decided to let their children plant rice.

SLOW CHANGE

It was not until 1950 when local political leaders lobbied for the system to be changed, that youth had an opportunity to study and work freely without changing their belief or preference.

“After 1950 the Indians developed a consciousness to educate their children. I was fortunate to be born in a time of change because I had an opportunity to teach, attend UG and even migrate and study abroad… now I am retired but still function as a Pandit,” said Singh.

Although times have changed, he said some of the cultures still exist, like the reading of scriptures and religious ceremonies.

Singh believes that a large part of the Indian culture has been diluted, in some cases for the better. He even pointed out that Bollywood music which was a big thing back then has been blended with English to form Chutney music and so forth.

The religious leader said the Indian culture has come a far way over the 180 years since their ancestors first set foot in Guyana.

HISTORY OF INDIAN ARRIVAL TO GUYANA

According to the history books, two ships, the Whitby and Hesperus were chartered to bring indentured labourers from India.

The Whitby sailed from Calcutta on the 13 January 1838 with 249 immigrants, and after a voyage of 112 days, arrived in Guyana on May 5 of that same year. Five Indians died on the voyage. The ship immediately sailed to Berbice and 164 immigrants, who were recruited by Highbury and Waterloo plantations, disembarked. The ship then returned to Demerara and between 14-16 May, the remaining 80 immigrants landed and were taken to Belle Vue Estate.

Of the total of 244 Indians who arrived on the Whitby, there were 233 men, five women and six children.

The Hesperus left Calcutta on the 29 January 1838 with 165 passengers and arrived in Guyana late on the night of the 5th May, by which time 13 had already died. The remaining 135 men, six women and 11 children were distributed between the 8-10 May to the plantations Vreedestein, Vreed-en-hoop and Anna Regina.