Risker, risk

<big>By Gaiutra Bahadur</big>

The Sky’s Wild Noise: Selected Essays, by Rupert Roopnaraine

(Peepal Tree Press, ISBN 9781845231613, 394 pp)

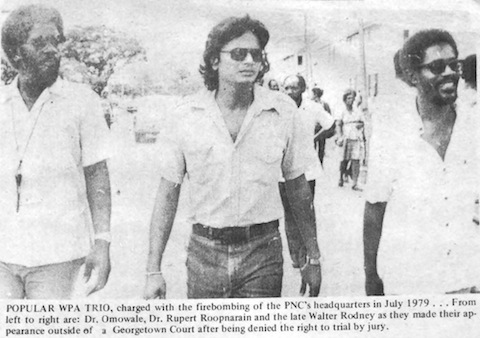

<small>Rupert Roopnaraine (centre) with Walter Rodney (right) and their WPA colleague Omowale in 1979, in a newspaper photograph published after Rodney’s death

</small>

The prose anthology The Sky’s Wild Noise takes its title from a line by Martin Carter, Guyana’s poet of resistance and one of the collection’s guiding spirits. The verse is part of an elegy, written in mourning for Walter Rodney, another of this book’s polestars. Rodney was killed by a car bomb in 1980, in the midst of a government crackdown against the party he led, but his brilliant example was not snuffed out. As historian and man, as public intellectual and radical, as transcendent figure, he still shines two generations later. It’s worth quoting the Carter poem at length:

I sit in the presence of rain

in the sky’s wild noise

of the feet of some who

not only, but also, kill

the origins of rain, the ankle

of the whore, as fastidious

as the great fight, the wife

of water. Risker, risk.

The assassin’s crime is deflected, revealed only indirectly: “not only . . . the origins of rain” have been killed. Rupert Roopnaraine, Rodney’s colleague in “the great fight” and the author of The Sky’s Wild Noise, recounts that a week of iron-fisted displays by the state’s security forces led up to the murder. The political police and its thug arm targeted supporters of the Working People’s Alliance, searching homes for arms and ammunition, and arresting, detaining, and torturing dozens. A scholar of international renown and global experience, Rodney was a threat to the regime when he returned home to Guyana, largely because he took lessons about divide-and-rule tactics out of the academy, into city streets and village bottom-houses, where he asked questions about contemporary as well as historical oppression. In the attempt to extract information to frame him, the detainees were burned with cigarettes and beaten with the butts of guns. Their heads were shoved into full toilet bowls. A senior police officer bit one prisoner. In the end, the state levelled charges of treason against five who were in custody and one who wasn’t.

It was Roopnaraine whom Rodney entrusted with keeping the sixth man underground, while the party sought sanctuary for him abroad. The night of the murder, the two leaders stood on a Georgetown pavement, talking. “Walter asked about progress, in detail,” Roopnaraine writes. “I told him what we managed so far. He urged caution. He said he had to check out someone at eight o’clock, that (his brother) Donald would drive him. We agreed to meet later that night. Perhaps dinner.”

They had just emerged from the weekly meeting of the WPA’s executive committee, where they and others had debated how best to answer the crackdown. Born within a year of each other, Rodney and Roopnaraine were peers: professors both — the former of history, the latter of comparative literature — and bearers both of degrees from prestigious British universities. Yet both had chosen to return to Guyana to serve it in “the dark time” of the 1970s, as President Forbes Burnham consolidated the power he had won with the CIA’s help and maintained through rigged elections. That night, they kept each other’s counsel before parting (briefly, they thought). As it unfolded, they did not meet for dinner. Before the night was out, Rodney was gone. Posthumously, his role has been that of moral lodestar: a symbol of the higher self that still eludes the Guyanese body politic, with Indians and Africans still divided in electoral contest, still scarred by the racial violence of the independence era.

•

In a sense, the role that Roopnaraine has played was the harder one: not martyr, but survivor. Over the decades, he has been many things: university lecturer, orator (often in eulogy), political prisoner (accused of burning down government buildings in 1979, and jailed), envoy to warring factions of the socialist revolution in Grenada, candidate, parliamentarian, and now education minister. But above and beyond all that, he has been the bearer of Rodney’s urgent message against racial polarisation, and he has been an eyewitness.

Indeed, his vivid first-person dispatches from the front lines of Caribbean revolutionary history provide some of the most riveting reading in The Sky’s Wild Noise. When invited to Grenada to mediate between its leader Maurice Bishop and the ex-comrades who put him under house arrest, Roopnaraine hears a barrage of automatic weapons, an unsettling lull, then a burst of machine-gun fire in the distance. That afternoon, he receives a phone call from the man who was to arrange his meeting with Bishop. “How is Maurice?” Roopnaraine asks. “How was Maurice, you mean?” comes the chilling reply. Stuck on the island in the aftermath, with the United States threatening to invade, Roopnaraine volunteers to help the leaders of the winning faction. It might prove that they executed the architect of the Anglophone Caribbean’s only successful working people’s revolt, an almost bloodless one. But faced with looming neocolonial aggression and the revolution’s complete implosion, Roopnaraine reasons, how could he not offer to help? He does a small part, eavesdropping on the phone calls home of American medical students until he is airlifted out with other British passport-holders.

Glimpses such as this give the greatest life and significance to The Sky’s Wild Noise. Snatch by snatch, piece by piece, they come together as a collage, a group portrait of the generation of leaders whose task it was not to oust the coloniser, but to contend with what came after. Born during the Second World War, these were the educated ones who, despite the mystique of their studies abroad, did not grow up to grow away (to borrow George Lamming’s phrase) from their origins. Instead, they returned home to make and in some cases unmake the postcolonial nation in the West Indies, to resist and in some cases to engineer its barbarities. The book documents the strivings and failings of this diverse group of agitators, which included the architects of coups such as Bishop and Suriname’s Desi Bouterse, and thinkers and writers such as Rodney and Roopnaraine, who is art and literary critic and poet as well as statesman.

The Sky’s Wild Noise is testament to his prodigious intellect, the depth and breadth of his interests, the pointed grace of his analytical prose. The book collates three decades of newspaper and journal articles, speeches, conference presentations, essays for art museum catalogues, and prefaces to literary publications. They are organised by subject (politics, art, literature, tributes) then, within each section, by the date each piece was written. The glimpses that Roopnaraine provides into a critical, dramatic period in Guyanese history are so immediate, so rare, they made me long occasionally for a more chronological structure. I wanted the narrative force of events presented as they unfolded. But the pieces don’t walk that straight line of time; instead, they gather as a group of intersecting circles, a geometry that reflects Roopnaraine’s outlook on the universe as interconnected. As he sees it, our identities, our addresses, our endeavours are all linked, black with Indian, city with countryside, our attempts to self-govern with our attempts to create. Recurring preoccupations hold the pieces together, but so does this thread of humanism. As Roopnaraine himself expresses it in his introduction: “Were I to isolate a single theme that runs through the essays on politics as well as those on literature and art, it is that of reconciliation, the recovery of oneness, oneness of being and oneness of practice.”

Perhaps no essay better conveys his respect for a unified vision, based in the spirit world, than “Philip Moore of Guyana and the Universe”, an appreciation of the work of the late sculptor and painter. A generation older than Roopnaraine, Moore was a self-taught artist born in Corentyne, in the far countryside. He carved his first piece in a cane field, after undergoing a mystical conversion. (He dreamed of a black hand holding out a chisel emerging from an illuminated cloud in the sky, commanding him to make art.) Moore was an elder in the Jordanite church, an evangelical form of Christianity rooted in African traditions. His religion shaped his art. But so did Hinduism. He was a carver of murtis, iconic images of Hindu gods and goddesses, for temples in the Indian-inflected landscape of Corentyne. And that influence shows.

This past June, I saw Moore’s work at Castellani House, Guyana’s national art gallery, a white wooden house in Georgetown’s elegant old colonial style, where Forbes Burnham once lived and where Roopnaraine sat to pen his essay on Moore almost two decades ago. The intricacy of the work impressed me; every inch of sculpture and canvas is crowded, with figures and with story. Just as striking as the number of figures, their very teeming, is how interconnected they are, in both the vertical and horizontal axes of the work. If you look from side to side or up and down, threads (a chain of faces or masks, or a procession of snakes) inevitably run across, linking one part organically to another. No part stands isolated. It reminded me intuitively of the story in the Upanishads of the cosmic thread that connects all souls, thesutra-atman in Sanskrit.

Roopnaraine remarks on the Hindu influences too, in dissecting the sculptureBat and Ball Fantasy, which he calls “a miracle of distillation and symbolic expression.” The three-by-eighteen-inch wooden sculpture represents a cricket match between two Guyanese villages. The batsman has four arms. Roopnaraine observes that many-armed figures are not unusual in Moore’s oeuvre. “It would be surprising if this carver of murtis did not draw from the rich store of Hindu religious imagery,” he writes. Moore’s signature connective threads — what Roopnaraine describes as “a drumbeat of visual rhymes and repetitions” — are present here too: ten linked suns frame the top; an iteration of cricket pitches, the bottom; and totems of repeating heads and clapping hands the left and right side of the sculpture, to signify the audience. In the thick of the sculpture, a small coffin and fowl cock with a smear of blood “tell a village tale.” They point to the intensity of the game between Whim and Moore’s own village, Manchester. (“A conflict of civilisations fought out in a remote corner of the British Empire,” Roopnaraine muses.) Before the game, an Obeah man from Manchester would walk the cricket ground with a coffin to capture the spirits of the Whim players. A pandit from a Kali temple in the Corentyne would handle the rival team’s black magic, with the sacrifice of a fowl cock in the cane fields the night before. Despite the competition that forms the subject of the sculpture, Roopnaraine notes its “wonderful harmon[y]” as a piece.

Roopnaraine reflects on the recurrence of bridges as a motif in Moore’s work. Four major paintings depict bridges, including one that Moore was working on as Roopnaraine was interviewing him for the essay discussed here. The Bridge of the Diaspora is allegorical. Others are actual bridges, like the “kissing bridge” for lovers in Georgetown’s Botanical Gardens. And Roopnaraine calls attention to the other bridges throughout Moore’s work, the unseen ones which “we need to build inside of ourselves if we are to integrate mind, soul, and body.” He asks, summing up so much, compressing the ironies and reversals of Guyanese history into one astounded question: “Could anyone in 1979, year of rebellion and sharp steel, have imagined that in 1996 I would be sitting in President Burnham’s attic thinking about art and its power to redeem? Philip Moore is the bridge I crossed to get here.”

•

Roopnaraine would cross other unimaginable bridges, too.

In Guyana’s 2011 election, the Working People’s Alliance joined in a coalition of opposition parties, including the one widely believed to have been responsible for Rodney’s murder. Roopnaraine was the alliance’s prime ministerial candidate. Its presidential contender was a retired brigadier general who had to contend with allegations that he played a role in the seizure of ballot boxes and the killing of two poll workers during Burnham’s rigged 1973 elections. After an extraordinary victory by the opposition coalition two months ago, in Guyana’s most recent general election, that candidate is now president, and Roopnaraine is a minister in his government.

As much as Rodney ever was, Roopnaraine was a hero of the great fight against that dictator, but his role has been to carry on and to carry on as the ruling party changed but society remained racially divided. Carrying on in this context involves compromise. It involves a hard reckoning with the self about what it means to lead and what constitutes true political courage.

Consider again those mysterious lines of the Carter poem: “the ankle of the whore, as fastidious / as the great fight . . .” Even the prostitute who, confronted with the exigencies of existence, sells her body, can reserve a part of it as no one’s commodity. The ankle abstains. The metaphor was conceived by Martin Carter. The poet had been a founding member of the socialist multi-racial alliance that fought for independence from the British, before that party split along ideological and then racial lines in the late 1950s. With that fission, Carter went to work as information officer for Booker’s, owner of most of the colony’s plantations, the very embodiment of British capitalism. Then he served as Burnham’s information minister for seven years. When he quit, with the famous declaration that the “mouth is always muzzled by the food it eats to live,” he retreated from active politics to the solace and integrity of the pen. With it, he gave expression to the corrosive effect that dictatorships can have on the souls of men, to “the culture of petty deception, of trade-off, sometimes of the traffic of another to the paymaster,” as one WPA member characterised the Burnham era. Or, as Carter once wrote: “All are involved.” All are implicated, through everyday negotiations for survival. The trick, the hope, the risk is somehow to preserve part of the soul, to keep an ankle fastidious.

Roopnaraine’s compromises are of a different kind, shaped by living not in a dictatorship but in a still-polarised society where all are involved, through unchosen skin. The definition of the great fight has shifted somewhat. Essay after essay in The Sky’s Wild Noise comes back to that greater fight for national reconciliation. The “fundamental predicament” of persisting racial competition haunts him. He turns to hopeful examples of an end to rancor on the world stage: to the power-sharing constitution that Nelson Mandela negotiated in South Africa, for instance. In essay after essay, Roopnaraine’s refrain is to reject the Westminster model of government, in which the winner takes all electoral spoils. In a place like Guyana, as long as one ethnicity constitutes a majority and ballots continue to be cast along racial lines, that is a recipe for domination by one ethnicity — through the tyranny of electoral math — and therefore for mutual failure. His current alliances are guided by that insight: that the only way forward is to share political power and to forgive former foes. In this light, conscience isn’t defined by purism of party or ideology, but by the need to transcend.

And, as incisive commentator on the arts and as poet of love and exile, Roopnaraine is as concerned with how we might achieve that for our souls as well as for our nation-states. In 1993, Roopnaraine published Suite for Supriya, poems for a woman clothed in a shawl of stars and long tresses. He dedicates one poem not to his beloved but to his late comrade, Martin Carter. “Risker, risk,” it begins.

Noble words for a fallen soldier.

I borrow them today in another season,

Not of loss this time

But of fullness of life beyond reason

Demanding boldness of rhyme

And readiness for reason beyond life

That heralds the warrior.

Roopnaraine has been a warrior himself, of course, one admired for his immense integrity. But his life has also been one spent heralding the assassinated warrior. For decades, he has been one of Rodney’s living messengers, an ambassador of the principles that guided his fallen colleague. He remains faithful to that role in The Sky’s Wild Noise, with its flashes of the interconnected lives of a generation of postcolonial agitators, artists, and thinkers, with Rodney at the centre. But the final lines of the poem gesture at a moment when the speaker has reason for being other than the great fight, when he is called to risk by loving rather than by engaging in the struggles of politics or national conscience. I’ve quoted Roopnaraine’s poem here in full, partly for symmetry’s sake, partly to punctuate with a humanistic hope that often seems elusive in our still fractured public sphere.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, July 2015

Gaiutra Bahadur is a Guyanese-American journalist who writes frequently about migration, literature, and gender. She is the author of Coolie Woman: The Odyssey of Indenture (2013), which was shortlisted for the 2014 Orwell Prize for political writing.