Seven Wonders of the Ancient World: The Most Magnificent Monuments of Antiquity

By April Holloway, 30 June, 2015 - 01:07, Source

The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World are seven awe-inspiring monuments of classical antiquity that reflect the skill and ingenuity of their creators. The list, comprised by ancient Greek historians, covers only the monuments of the Mediterranean and Middle Eastern regions – the known world for the Greeks at the time.

Today, only one of the Seven Wonders remains intact – the Great Pyramid of Giza. Three of the Wonders – the Colossus of Rhodes, Lighthouse of Alexandria and Mausoleum of Halicarnassus – were destroyed by earthquakes. Two of the Wonders – the Temple of Artemis and Statue of Zeus – were intentionally destroyed by enemy forces, while the final Wonder – the Hanging Gardens of Babylon – has remained a matter of contention for millennia, with some historians questioning whether existed at all.

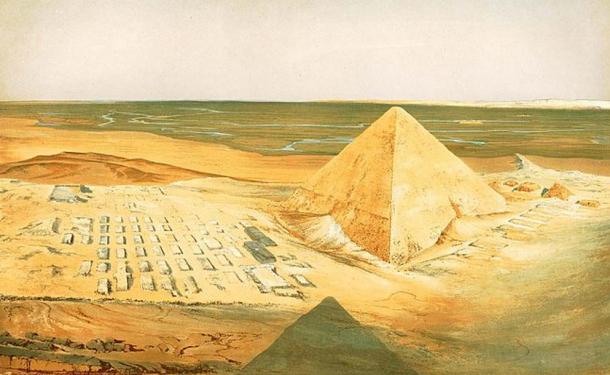

The Great Pyramid of Giza (also known as the Pyramid of Khufu or the Pyramid of Cheops) is the oldest of the Seven Wonders, and the only one to remain largely intact.

It is estimated that the Great Pyramid is comprised of more than 2 million limestone blocks weighing from 2 to 70 tons. Originally standing at over 140 meters (481 feet), the Great Pyramid was the tallest man-made structure in the world for over 3,800 years. It was built with such precision that it would be difficult to replicate it even with today’s technology.

After the Great Pyramid of Giza, the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus is the longest surviving wonder of the ancient world, having stood for more than a millennium and a half. The Mausoleum of Halicarnassus was built for Mausolus, the second ruler of Caria from the Hecatomnid dynasty (and nominally a Persian satrap) who died in 353 BC. As the man who refounded Halicarnassus, Mausolus was entitled to receive cultic honours and a tomb on the central square of his city, in accordance with Greek custom. The final construction was a wonder built in the styles of three different cultures – Greek, Lycian and Egyptian.

During the 13th century, a series of earthquakes destroyed the columns of the Mausoleum, and brought the stone chariot, which sat atop the Mausoleum, crashing to the ground. By the early 15th century, only the base of the structure was recognisable. By the end of the same century, and again in 1522, following rumors of a Turkish invasion, the Knights of St. John used the stones from the Mausoleum to fortify the walls of their castle in Bodrum. Additionally, much of the remaining sculptures were ground into lime for plaster, though some of the best works were salvaged and mounted in Bodrum castle. During the 19th century, the last remnants of the Mausoleum, including sections of relief, a broken chariot wheel, two statues, and some foundations, were unearthed by British archaeologist Charles Thomas Newton and taken back to the British Museum, where they remain to this day. They are the last remnants of a once spectacular monument that had the ancient world in awe.

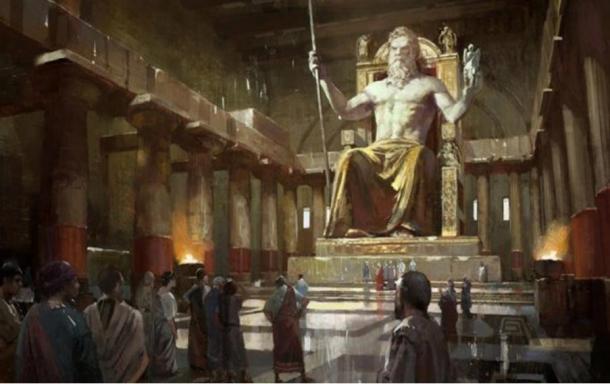

The statue of Zeus at Olympia, Greece, was arguably the most famous statue of its day. Once built as a shrine to honor the Greek god Zeus, this statue was considered the incarnate of the Greeks’ most important god, and not to have seen it at least once in one's lifetime was considered a misfortune. The size of a four story building and seven times the height of an average man, it was the tallest statue of the Mediterranean world.

According to legend, the altar of Zeus stood on a spot struck by a thunderbolt, which had been hurled by the god from his throne high atop Mount Olympus, where the gods assembled.

The statue of Zeus was made by the Greek sculptor Phidias in 430 BC, considered the most famous artist of ancient Greece. The giant figure was made from a wooden frame of cedar wood covered with expensive materials such as ivory, ebony, bronze, gold leaf and precious stones. Zeus wore a robe and pair of sandals made out of gold. The stool beneath his feet was upheld by two impressive gold lions. In his left hand was a scepter crowned with an eagle's head symbolizing his dominion over Earth. In his right hand sat a life-size statue of Nike, the winged goddess of victory.

The statue of Zeus sat in place for over 800 years until Rome’s new Christian emperor Theodosius I ordered the statue dismantled and stripped of its gold in 391 AD. Today, all that remains in Olympia are the temple's fallen columns and the foundation of the building, which were uncovered during 19th and 20th Century archaeological digs.

The Pharos of Alexandria was the most famous lighthouse in antiquity. The incredible feat of ancient engineering stood at an impressive height of 130 meters (430ft) until it was destroyed by an earthquakes in the 14th century AD. Built either late in the reign of Ptolemy I or early in the reign of Ptolemy II, around 280 BC, the lighthouse was located on the eastern tip of the island of Pharos. In some descriptions, it is recorded that a huge statue, representing either Alexander the Great or Ptolemy I in the form of the Sun God, Helios, stood on the top of the lighthouse. This would have been an obvious message to anyone entering Alexandria by sea that the city was now under ‘Ptolemaic management’.

Besides being a propagandistic symbol of Ptolemaic legitimization, the Pharos was also a guide for sailors to the harbor. Alexandria was a very important city in Ptolemaic Egypt, as it was not only its capital, but also its gateway to the Mediterranean. Hence, the building of a lighthouse to ensure that ships, especially those of merchants, could safely arrive at Alexandria’s harbor would have brought economic benefits to the Ptolemies.

The lighthouse was damaged by a series of earthquakes between 3rd and 12th centuries and is believed to have been completely destroyed in the early 14th century. In 1994, hundreds of huge masonry blocks from the original lighthouse were found in waters off the island.

The real location of the elusive Hanging Gardens of Babylon has eluded researchers for centuries. It is the only one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World whose exact location is still unknown.

The most commonly held belief in scientific circles is that the ancient city and hanging gardens was constructed by the Babylonians under the leadership of king Nebuchadnezzar II, who ruled between 605 and 562 BC. He is reported to have constructed the gardens to please his homesick wife Amytis of Media, who longed for the plants of her homeland.

Because of the lack of evidence it has been suggested that the Hanging Gardens are purely mythical. Nevertheless, descriptions of the gardens exist in several ancient Greek and Roman texts and many historians insist the descriptions were based on a real place.

The Temple of Artemis once stood as a magnificent structure three to four times as large as the Parthenon in Athens in the ancient city of Ephesus. It was described as the largest temple and building of antiquity and served as a place of worship to the Greek Goddess Artemis. Home to both Greeks and Romans, the grand temple was destroyed and rebuilt many times over the course of its long history.

The ancient temple was built around 550 – 650 BC and on a site already sacred to the Anatolian Mother Goddess, Cybele. For years, the temple was a site visited by merchants, tourists, artisans, and kings who paid homage to the goddess Artemis by sharing their profits with her. It was the home of priests and priestesses, musicians, dancers, and acrobats. The temple was also a marketplace housed many artworks. Sculptures by renowned Greek sculptors such as Polyclitus, Pheidias, Cresilas, and Phradmon adorned the temple, as well as paintings and gilded columns of gold and silver.

According to the Greek historian Strabo, the Temple of Artemis was rebuilt seven times over ten centuries, though the exact number is uncertain. In 401 AD, the temple was finally destroyed by a mob of Christians. Much of the Temple of Artemis remained undiscovered until 1869 when a team of British Museum archaeologists, led by John Turtle Wood, found the remains and foundations after a seven year long search. Today the site is little more than a ruin.

The Colossus of Rhodes was the most ambitious and tallest statue of the Hellenistic period. The last of the seven wonders to be completed, it was a statue built to thank the gods for victory over an invading enemy.

In 357 BC, the Greek island of Rhodes was conquered by Mausolus of Halicarnassus but fell into Persian hands in 340 BC and was finally captured by Alexander the Great in 332 BC. In the late fourth century BC, Rhodes allied with Ptolemy I of Egypt against their common enemy, Antigonus I Monophthalmus of Macedonia. In 305 BC, Antigonus sent his son Demetrius to capture and punish the city of Rhodes for its alliance with Egypt. He attacked the island with 40,000 men but a relief force of ships sent by Ptolemy arrived in 304 BC, and Antigonus’ army abandoned the siege, leaving behind most of their siege equipment. To celebrate their victory, the Rhodians sold the equipment and used the money to build a huge statue, to their sun god, Helios, called the Colossus of Rhodes. The Colossus was said to have been fashioned from the melted down bronze weapons of the defeated invaders.

The statue stood for only 56 years until the island of Rhodes was hit by an earthquake in 226 BC, destroying much of the city and causing the statue to break off at the knees and topple over into pieces. The statue would go untouched for 900 years or until the Arab invasion of Rhodes in 654 AD. The remains are said to have been melted down to be used as coins, tools, and weapons.