South Asia monsoon: Analysing fresh water could be key to forecast

The Indian Ocean contains a distinctive layer of fresh water from rain and rivers which may influence the South Asian monsoon, scientists have said.

They are urging meteorologists to include the less saline water in their weather forecasting models.

Meteorology officials in South Asia admit they have been slow to consider the role of fresh waters.

They are already struggling to forecast monsoon rains due to a range of factors including climate change.

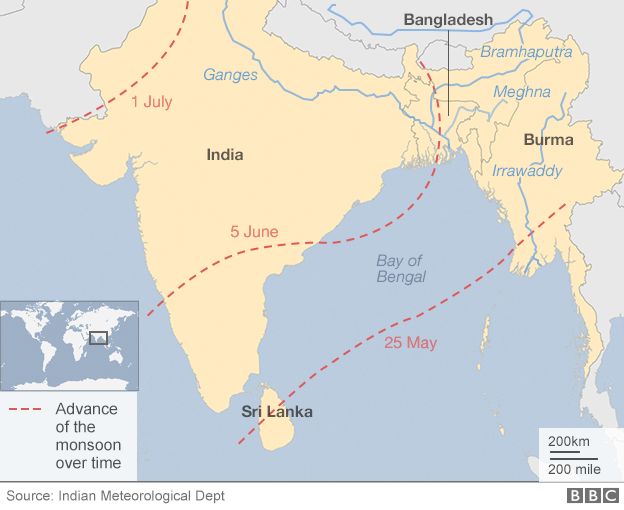

Monsoons account for 70% of the rainfall in India and neighbouring countries between June and September.

But longer dry periods and heavy rainfall within a short space of time during monsoon season in recent years have caused concern in South Asia.

And this is already being seen this year, with higher rainfall than normal in June - whereas July and August are predicted to have lower than normal rainfall.

Missing link?

Some meteorologists based in the region believe the freshwater element could be a vital missing link.

Major rivers such as the Ganges, Bramhaputra and Irrawaddy flow into the Bay of Bengal.

A team of international scientists are currently researching the issue.

"Freshwater inputs from both rivers and a large amount of rainfall make the Bay of Bengal a rather unique place, and that is not properly being taken into account in the monsoon forecast models," said Professor Eric A. D'Asaro, an oceanographer at the University of Washington, who has been researching the Bay of Bengal with scientists from India and the US.

"And that's one of the reasons they are not able to forecast what are known as monsoon breaks - in other words the variations on monthly time scales through the monsoon season.

"The fresh water makes the surface layer of the ocean water much thinner and lighter and that reacts with the monsoon clouds more strongly whereas saline water would do so more slowly and that would have less effects on the monsoons."

Researchers with the Ocean Mixing and Monsoon project say they have found a "sharp separation between river water and seawater on scales ranging from 100m to 20km".

The deputy director general of Bangladesh's Meteorology Department, Shamshuddin Ahmed, is receptive to the research.

Their monsoon prediction model is currently based on the speed of wind, its direction and the amount of water vapour in the atmosphere.

"I am not aware of any modelling in our region that considers the role of fresh waters in shaping the monsoon," said Mr Ahmed.

"But I think for accurate long-range monsoon predictions, we need to do some serious studies on fresh waters and get it in our models."

Pakistan's meteorological officials said they downgrade the data from the global model and look for the sea surface temperature to predict monsoon rains for their country.

They admit fresh water is not something they look into even when they are using the sea surface temperature.

Around 60% of the total rainfall in Pakistan comes from the Indian monsoon, while the remaining rains are from winter monsoons from the Arabian sea between December and February.

"It's not just scientists from Pakistan but from the entire South Asia region who are not familiar with the fresh water concept and we need to take it into account," said Mohammed Hanif, a director with Pakistan's meteorological department.

India 'lukewarm'

Scientists with the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology, an autonomous body, agree that their models need to be updated, factoring in the interaction between fresh waters and the monsoon.

However, the head of the Indian government's meteorology department, LS Rathore, said the issue was still unclear.

"Sea surface temperature certainly effects monsoon circulation but that has more bearing on the long term.

"So far, there is a very hazy kind of understanding on this subject: let research make things clearer first."

But scientists say even if countries around the Bay of Bengal really wanted to factor fresh water into their monsoon prediction models, detailed data was not available.

"At present we only have long-term mean data on the river discharge and we have no data for year-to-year variability because of the sensitivities between countries in the region," says Professor BN Goswami, an Indian climatologist involved in the research project in the Bay of Bengal.

"The year-to-year variability data for fresh water inputs into the ocean will be very important to understand their influence on the monsoon."

Sharing of water resources data has been a contentious issue between India and its neighbours for years.

"The countries will have to reach an understanding if they really want to understand what fresh water is doing to the salinity of the ocean and the monsoon systems," said Professor Goswami.