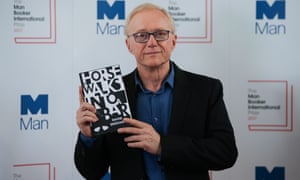

The Man Booker Prize, one of the shiniest baubles and most generous purses in English letters, was awarded today to the American writer George Saunders for his novel “Lincoln in the Bardo.” The occasion invites us to reflect on how the residue of slavery and white supremacy permeates our cultural life, and determines whose histories are celebrated and whose are erased.

There is a dark side to the Booker brand. It has unpaid debts to humanity. It has unleashed continuing agony in places like Guyana, where the Booker brothers founded a sugar firm in 1834. Earlier this year, we lost at age 90 the great novelist and art critic John Berger who tried to bring attention to the problematic nature of Booker’s history in Guyana. In a fiery 1972 acceptance speech for the Booker prize for his novel “G,” Mr. Berger blasted the London-based Booker McConnell sugar firm’s exploitation of Guyana and African slavery’s role in funding the Industrial Revolution. He pledged to donate half the 5,000 pound prize money to the Black Panther Party. (The other half would fund a project on migrant workers.)

During my own research for a coming book about art and resistance in my parents’ native Guyana, I came across a collection of documents held by Britain’s National Archives that demonstrated the kind of casual racial opportunism that should also be associated with Booker. In 1815, soon after the British successfully elbowed away Dutch, French and Spanish rivals to claim the small patch of rain forest land at the northern edge of South America, 22-year-old Josias Booker left Britain to help manage a cotton plantation in what was then British Guiana.

Soon, he invited his brothers, George, William and Richard, to join him in the hottest new start-up industry: sugar. In addition to growing cane harvested by enslaved African workers, the brothers established their own ship fleet and incorporated as Booker Brothers & Co. in 1834.

The first threat to the family business came when British Parliament voted to abolish slavery in 1833. Lucky for the Booker brothers, key members of Britain’s political, religious and banking institutions also had considerable slave holdings. Investors convinced debt-ridden Parliament to pay out 20 million pounds (about £2 billion in today’s currency, or about $2.6 billion) to compensate slave owners across the empire. it was the largest bailout in global history until the bank bailout of 2009.

Parliament’s bailout scheme richly benefited the Bookers. Slave owners negotiated immediate cash payments to compensate for the loss of their work force — according to calculations made by the historian Hilary McD. Beckles in his book “Britain’s Black Debt,” politically powerful British Guiana owners got about of 50 pounds per slave, while older colonies such as Barbados and Jamaica fetched 20 pounds. Since the actual market value of this human chattel was set at 47 million pounds, Parliament decreed that my enslaved Guyanese ancestors had to work as unpaid “apprentices” for a period of several years after the owners cashed out to pay off the rest of their own market value.

The Booker brothers and their associates collectively submitted claims on 52 slaves, giving their fledgling business a cash injection of what amounts to 317,240 pounds (about $418,000) in today’s currency, according to archives. Because many British Guiana planters used abolition of slavery as an opportunity to liquidate their human assets and get out of the sugar business, the Booker brothers were able to acquire them cheaply. Their enslaved work force grew to 315 people in the period immediately following emancipation. After squeezing the workers for four more years of unpaid labor, on Aug. 1, 1838, at the appointed time, the Booker brothers manumitted them. “Today I had the privilege of mustering the slaves and giving them the good tidings that they were free, resulting in great rejoicing throughout the plantation,” George Booker wrote in a letter to his brother Septimus.

Rather than pay fair wages to free African workers, British planters such as the Bookers convinced the British government to help finance voyages to collect replacement sugar workers — indentured workers from India. British Guiana was first in line to receive these workers, and by the time the practice ended in 1917 amid gross human-rights abuses, the colony had received 240,000 Indian indentured workers. People of East Indian descent remain Guyana’s largest ethnic group, and continue to be locked in an often bitter competition with the African workers whom colonial society sought to discard as surplus.

The Booker family moved on and passed its holdings over to a partner, McConnell, in the 1880s, and the Booker McConnell brand continued to expand. The company went public on the London Stock Exchange in 1920. Booker McConnell used this fortune to establish a world empire of its own.

It also aggressively expanded within British Guiana. After World War II, Booker owned 15 of the remaining 18 sugar estates. Just as it took over failed sugar plantations, the firm took over many other businesses in British Guiana: real estate, retail stores, transportation, pharmaceuticals, insurance, advertising, newspapers, radio stations. The company’s domination of the economic and political life was so complete that the colony became acidly referred to as “Booker’s Guiana.” At the time Mr. Berger gave his 1972 speech, Booker was still drawing 45 percent of its profits from British Guiana, according to company records.

By calling attention to this exploitation in Guyana during his Booker Prize acceptance speech, the white British writer Mr. Berger echoed local leaders such as Dr. Cheddi B. Jagan. In fiery speeches and pamphlets, Mr. Jagan, an American-trained dentist whose Indo-Guyanese family had been employed by Booker for generations, exposed how “Big Sugar,” based in London, dodged taxes and refused to invest in local infrastructure. When Mr. Jagan was elected chief minister of British Guiana in 1953, the first election under universal suffrage, British authorities sent troops to remove him from power.

After the British left for good in 1966, the United States picked up the baton of control by meddling in Guyana’s elections, working through the C.I.A. to undermine Mr. Jagan, according Cold War historian Stephen G. Rabe and others. The country did not have what were considered free and fair elections until 1992, when Mr. Jagan, among the country’s most effective critics of sugar, returned to power as president.

Like more than half of the people born in Guyana, my parents left. They departed in 1970. The country of their birth has one of the world’s highest emigration rates. Fifty years after independence, Guyana has virtually fallen off the global map. It is now the second-poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, behind Haiti. Its currency trades at $200 to $1 U.S. Guyana has the world’s second-highest suicide rate, nearly double the global average.

Facing global erasure, amid economic, racial and political turmoil, Guyana’s poets, painters and musicians are creating epic, bravura displays of resilience, vitality and cultural memory. If not for the accident of history, I imagine these artists would get the kind of resources, support and recognition that are rightfully lavished upon the nominees of the Man Booker Prize.

So, by all means, let’s celebrate the literary excellence achieved by George Saunders and all the nominees of this year’s Man Booker Prize. As we do, let’s recognize the people who have paid its price.