Justice in Pakistan: 'The government is hanging people left, right and centre'

Since December 2014, Pakistan has executed more than 100 prisoners. For the lawyers defending inmates on death row, life has never been so tough

Joe Sandler Clarke, @JSandlerClarke, Friday 5 June 2015 11.06 BST, Source

The aftermath of last year’s massacre by Taliban militants in Peshawar which left 132 children dead. The government lifted a moratorium on the death penalty after the attack. Photograph: A Majeed/AFP/Getty Images

Shafqat Hussain was sentenced to death for murder when he was 14. In the 11 years since, he has been granted three last-minute reprieves, most recently last month, just hours before he was due to be hanged.

But in a country with an estimated 8,000 people on death row, Hussain’s case is far from unique. And for the handful of human rights lawyers who have committed themselves to the job of defending these inmates, justice can be hard to come by.

“The government has started hanging people left, right and centre in order to look tough,” says Saroop Ijaz, one of the beleaguered and overworked human rights lawyers working in the country.

Since a moratorium on capital punishment was lifted in December 2014 in response to the murder of 132 children in the Peshawar school massacre, Pakistan has executed prisoners at a rate of more than one every two days, with more than 100 deaths so far. Amnesty International has described the decision to reinstate the death penalty as a “shameful retreat to the gallows” which is “no way to resolve Pakistan’s pressing security and law-and-order problems”.

In the country’s anti-terror and narcotics courts, the death penalty has become the de facto punishment, according to human rights defenders. “The attitude is that if they’re innocent, the high court will set them free,” argues Shahzad Akbar, a fellow for Reprieve and director of the Foundation for Fundamental Rights, a small legal charity that works to protect the rights of Pakistanis caught up in the justice system.

If you’re rich, you'll have the best lawyer and you'll get away with it

Saroop Ijaz

Of the thousands of inmates on death row, around 800 were charged with terrorism offences. As with Hussain, who was tried in an anti-terror court for the killing of a seven-year-old child near the building site where he worked, these cases often stretch the definition of what terrorism is. The death penalty is also the go-to punishment for offences ranging from treason to blasphemy.

Human rights organisations, including Amnesty, describe Pakistan’s justice system as “riddled with serious fair trial issues at every level” where allegations of torture are rife throughout the police force. To further complicate things, Diyya, a system which gives the legal heirs of the deceased an option to forgive the defendant and seek blood money from their family, is sometimes used as a mechanism to resolve murder cases and has created a two-tier justice system.

Introduced as part of the Islamification of the country’s penal code in 1990, families can buy their relatives’ freedom for about £34,000 – with Diyya pegged to the current market value of 30.63kg of silver. For critics of this system, the use of blood money amounts to the effective privatisation of Pakistan’s legal system.

“If you’re rich, you’ll have the best lawyer and you will get away with it,” argues Akbar. “The majority of death row prisoners are poor people who have had crappy lawyers.”

Hussain’s lawyer, Sarah Belal, 36, from Justice Project Pakistan (JPP), calls the state of Pakistani justice “a travesty”, with the death penalty targeting the “most vulnerable members of society”.

An Oxford graduate, Belal returned to Pakistan in 2009 to practise human rights law. In the time she’s been back in the country her team at JPP have represented detainees at Bagram airbase, victims of police torture and other individuals caught up in the war on terror.

My friends think I’m wasting my time. But when you’re able to save someone’s life, it makes your work worthwhile

Shahzad Akbar

JPP works pro bono, relying on donations from organisations like Reprieve and local philanthropists. “With the amount of cases we get through, if I wasn’t pro bono I’d be the richest lawyer in Pakistan,” she jokes.

Akbar and Ijaz also find themselves in demand, though their success rate is low. “Around 5%,” according to Akbar.

Since the Peshawar attack, Akbar has worked almost exclusively on cases where the death warrant has already been issued. Previously, he had represented clients in the high court. He frequently uses Diyya to try and get his clients free. He works in a challenging environment, facing opposition from the public as well as the state.

“Support for capital punishment has been linked to counter-terrorism, nationalism and religion. This narrative gives the state an opportunity to challenge human rights defenders and NGOs,” explains Ijaz, who combines his legal work with conducting research for Human Rights Watch.

“The state has created a national conversation which is us versus them, in more ways than one. The state’s rhetoric is designed to weaken the international human rights community in Pakistan. The death penalty is merely the peg that is being used for this.”

“My friends think I’m wasting my time,” he confesses. “But when you’re able to save someone’s life, it makes your work worthwhile.”

Despite the last-minute reprieve, the threat of execution still hangs over Hussain. After more than a decade in custody, the odds of him ever being released are long, but as a woman in a male dominated justice system, Belal is used to being the underdog.

“There are advantages and disadvantages with being a woman in Pakistani justice. You are an anomaly. There’s very few women in criminal justice,” she explains.

“But there’s an advantage in that you’re always underestimated. Going to a jail and meeting our clients, people are so shocked to see a woman that you can get in before they know what’s hit them.”

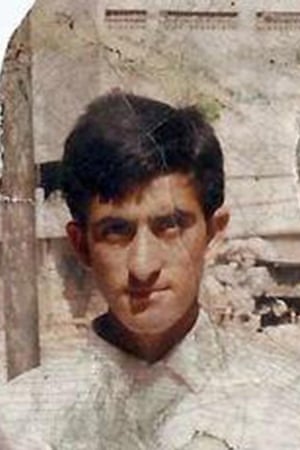

Shafqat Hussain: “I want to live a normal

life like everyone.” Photograph: Reprieve

For one of Belal’s clients, the road to freedom seems a long one.

Hussain’s family who hail from an impoverished village in rural Kashmir, 2,000km from Karachi, cannot use blood money to resolve his case.

His lawyers, from JPP contend that he was 14 and working as an undocumented juvenile when he was arrested, though the matter of his age at the time of the offence is disputed by the prosecution. They also state his confession to the murder was extracted through torture. Under Pakistani law, the death sentence cannot be imposed on a defendant who was under 18 at the time of the offence and testimony obtained by torture is inadmissible in trials.

With a learning disability and little formal education, assessments carried out by Hussain’s legal team have found that he has an IQ of between 40 and 60. He has only learned to read and write during the decade spent in the cramped and overcrowded Karachi central prison. With capacity of between 1,500 and 2,000 inmates, it has current population of more than double that at 5,000, according to JPP.

Speaking to the Guardian, through his legal team, Hussain called on the Pakistani government to review his case.

“I am not a criminal. I want to be a free man and be a part of the society and live a normal life like everyone else,” he says.

“Freedom is truly a blessing. I miss being able to spend time with my family and friends.”