A century after India ended the system of indentured labour, its diaspora is building a shared identity.

| PORT LOUIS, MAURITIUS

https://www.economist.com/news...ts-diaspora-building

DOOKHEE GUNGAH, born of Indian migrants, began life in 1867 in a shed in Mauritius and worked as a child cutting sugar cane. By his death in 1944, he was one of the island’s richest businessmen. He is a notable example of how some indentured labourers prospered against the odds.

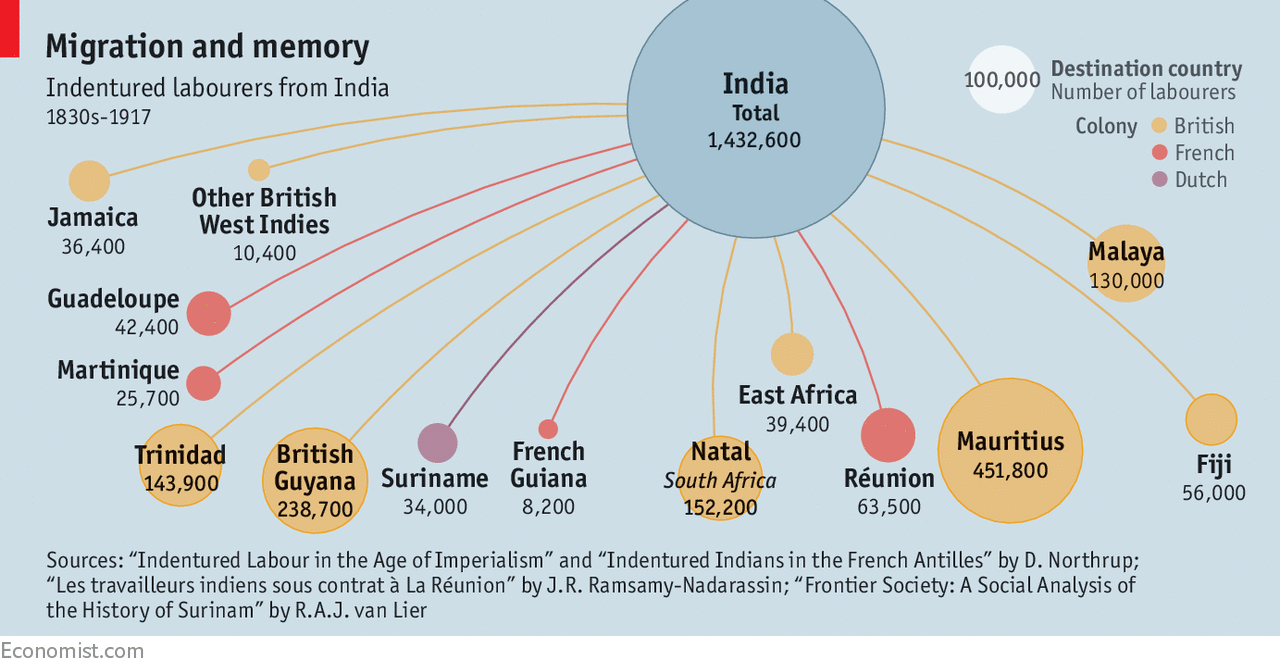

Between the 1830s and 1917 around 2m migrants signed up for ten-year terms (later cut to five) in European colonies (see chart on next page). Most were from India, with smaller shares from China, South-East Asia and elsewhere. Some “coolies” were fleeing poverty and hunger; others were coerced or deceived. In British colonies from 1834, and in French and Dutch ones from later, they replaced freed African slaves on sugar and coffee plantations.

“Slavery under a different name” is how The British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society described the indenture system in 1839. It had a point. Many migrants died en route, and at first plantation owners, used to slaves, treated their new workers hardly any better. But conditions gradually improved. When the Indian Legislative Council finally ended indenture, a century ago, it did so because of pressure from Indian nationalists and declining profitability, rather than from humanitarian concerns.

The indentured labourers’ fortunes varied from place to place, according to their numbers, who else lived there, and laws about land tenure and race. But a shared post-colonial identity is now emerging, combining pride in India’s economic rise, religious and cultural traditions—and, increasingly, commemoration of their ancestors’ struggles to establish themselves.

Indo-Mauritians are among the richest and most politically powerful of those descendants. As a British colony, Mauritius took the greatest share of indentured migrants: some 450,000. Their descendants are now two-thirds of the island’s 1.26m inhabitants. Many of the largest businesses are owned by Franco-Mauritians whose ancestors dated from the earlier French colonisation, though they make up just 2% of the population. But Indo-Mauritians dominate the public sector.

Local legend has it that Dookhee (pictured with family, third man from left, around 1912) owed his meteoric rise to finding buried treasure. The true story, says his great-grandson, Swetam Gungah, is that “whatever little he had, he would put it aside.” Unlike slaves, indentured labourers were paid, and since most were unable to leave their plantations, they spent little. Aged 21 Dookhee bought land and started growing sugar cane. “He was savvy enough to diversify. He planted an orchard, started a bakery and much more,” says Mr Gungah. When the price of sugar plummeted in the 1880s most plantation-owners went broke. Dookhee got richer. Other former indentured labourers were also able to buy broke colonists out. By 1933 Indo-Mauritians owned almost two-fifths of all land planted with sugar cane.

Land also gave indentured labourers a start in South Africa, where many were granted plots after their servitude. Koshir Kassie’s great-grandfather arrived in the province of Natal and worked on a plantation and then in a gold mine. He saved enough to pay his employer to end his contract early, and bought land. But under apartheid many Indian South Africans, including Mr Kassie’s family, were forced off their land and into Indian townships. “After indenture, Indians built themselves up,” says Mr Kassie. “Then came apartheid and they had to start again.”

Many managed to rebuild. Today, Indian South Africans’ average income is three times higher than that of black South Africans, and they are nearly twice as likely to have finished high school. But these days they are politically marginalised. In the first democratic elections, in 1994, two-thirds voted for the National Party, which had previously defended apartheid. Those with less education particularly resent South Africa’s new system of racial preferences in jobs and education for blacks.

Seeds in fertile ground

Indentured labourers in Trinidad and Guyana (formerly British Guiana) were also granted land. That was less generous than it seems: much of it was ill-suited to growing sugar cane. The Indians, however, discovered it was perfect for rice. Many prospered. But in both places, though people of Indian origin are the largest ethnic group (35% and 40% respectively), they have struggled to gain the level of influence that Indo-Mauritians have.

In Mauritius the departing British colonists regarded Indians as the heirs to power. In Trinidad, however, the mantle was passed to Afro-Trinidadians, who were settled decades before the indentured labourers arrived. Politics and the public sector operated through a patronage system, which kept Afro-Trinidadians in charge. Even after independence in 1962, Indo-Trinidadians were largely excluded from government and public-sector jobs.

Today, politics is still divided on ethnic lines, with the People’s National Movement supported by Afro-Trinidadians and the People’s Partnership coalition supported by Indo-Trinidadians. But socially, the groups are mingling more—and increasingly intermarrying. Nearly a quarter of the population identifies as mixed-race.

In Guyana ethnic divisions cut much deeper. Compared with Trinidad, its sheer size meant ethnic groups formed more segregated communities. A fragile inter-ethnic harmony, nonetheless, prevailed for the first half of the 20th century. That ended in 1964, when a pre-election conflict broke out between the largely Afro-Guyanese People’s National Congress and the largely Indo-Guyanese People’s Progressive Party. “I had Hindu friends, African, Portuguese, Chinese friends,” says Khalil Ali, a Muslim Indo-Guyanese novelist, of growing up in the 1950s and 1960s. “Then suddenly my black friends stopped speaking to me and I stopped speaking to them.” The resulting violence led to hundreds of deaths and thousands fleeing abroad.

Ethnic divisions persisted after independence in 1966, and were worsened by economic hardship. Even as Trinidad boomed because of oil, disastrous left-wing policies reduced resource-rich Guyana to one of South America’s poorest countries. But in 2015 a multi-racial coalition came to power, promising unity. Although change is slow—the government is still mostly Afro-Guyanese and Mr Ali says Indo-Guyanese who joined the coalition have been called traitors—elections in 2020 offer another glimmer of hope. Younger Guyanese are further distanced from the events of the 1960s. The mixed-race population, now around 20%, is growing.

Indentured workers’ descendants have done least well where their ancestors could not own land, as in Fiji. Its indigenous population resented the new arrivals, and the British made promises about land ownership to their tribal chiefs. Many Indo-Fijians became tenant farmers, and for part of the 20th century did quite well, says Crispin Bates, who leads a project funded by the British Arts and Humanities Research Council entitled “Becoming Coolies”. But when their leases came to an end, starting in the 1980s, their status declined.

Sporadic attempts to improve their position after independence in 1970 ended with a coup in 1987. A new constitution reserved majorities for ethnic Fijians in both houses of parliament. Over 10,000 Indo-Fijians left the island as a result. Two further coups centred on their rights. Finally, in 2013 Indo-Fijians were given equal status in the constitution. And, in 2014, in free elections, Frank Bainimarama (who led the most recent coup, in 2006) won with an anti-racist message. His task is considerable: though land has been made easier to lease, holdings by ethnic Fijians still cannot be sold. Indo-Fijians are still excluded—and ethnic Fijians are newly aggrieved. Anti-Indian sentiment is rampant.

Pride and prejudice

In most places that took indentured labourers, racial animus persists. Their arrival was “a real trauma” for indigenous and former-slave populations, says Mr Bates. In Trinidad and Guyana “coolie” is used as a slur (and the Indo-Guyanese and Indo-Trinidadians have plenty of racist terms for their compatriots of African origin). In Fiji and the French Caribbean “z’Indiens” are stereotyped as money-grubbing, and mocked in expressions such as “faib con an coolie” (“weak as a coolie” in Guadeloupian creole). In the 1970s a Fijian politician, Sakesai Butadroka, said in parliament that “people of Indian origin” should be “repatriated back to India”. As recently as 2014 a popular song by the Zulu band, AmaCde, called on black South Africans to confront Indians and “send them home”.

Strangers in strange lands, indentured labourers and their descendants preserved some traditions, from caste practices to recipes. From the 1880s the Arya Samaj, a religious group, attempted to reinstate Hindu culture in the diaspora—which rallied, in turn, behind Gandhi’s Indian nationalist movement in the 1920s and 1930s. During periods of ethnic strife in the 20th century hyphenated-Indian communities turned inwards for self-protection.

In recent years, though, a new kind of “Indian pride” has begun to take form. Mauritius has had strong links with India since post-independence tax and trade deals. But of a recent visit to Mauritius, Ashutosh Kumar, the author of a new book about indenture, “Coolies of the Empire”, says “the way Mauritians were discussing Indian politics: it was like I was back home in India.” In Trinidad, which got its first Indo-Trinidadian prime minister in 1995, there is “a new sense of Indian cultural pride”, says Andil Gosine, an Indo-Trinidadian academic in Canada. “When I go back now I see loads of people wearing saris, which they wouldn’t have done before.”

This cultural revivalism is, to some extent, the work of Hindu nationalists, particularly the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (World Hindu Council). It has recently devoted more attention to the diaspora—and stirred up tensions between Hindus and Muslims. More is due to India’s rise as an economic power. Diaspora Indians are seeking to “bask in the reflected glory of their motherland”, says Mr Kumar.

Khal Torabully, a Mauritian poet of mixed Indian descent, has coined the word “coolitude” for a new identity, which mixes heritage from India and the other sending countries with a century of history in racially diverse former colonies. Acknowledging their ancestors’ servitude as part of that can be uncomfortable. Indian South Africans are “proud to be Indian”, says Mr Kassie, but “don’t like to talk about indenture much”. Mr Gosine recalls his grandfather describing his own grandfather: “A Brahmin, riding around the plantation on a horse, dressed all in white. But then my grandmother chipped in: ‘What on earth are you talking about?’”

Making sense of displacement and difference, struggle and success, is also a work in progress for host countries. But some have started to weave the history of indentured labourers into their national narratives. In 2006 Aapravasi Ghat, where they first arrived in Mauritius, was recognised as a UNESCO world heritage site. In the same year the Indian Caribbean Museum opened in Waterloo, Trinidad. Last year the 1860 Indian Museum, dedicated to indenture, opened in Durban. “We still have a lot of problems to think of ourselves as Mauritians,” says Mr Torabully. “But remembering indenture, just as we remember slavery, is at the heart of that identity.”