The partition of India

Divide and rue

An clear and highly readable account of a disputed topic

Feb 21st 2015, Source - Economist

The Longest August: The Unflinching Rivalry Between India and Pakistan. By Dilip Hiro. Nation Books; 528 pages; $35.

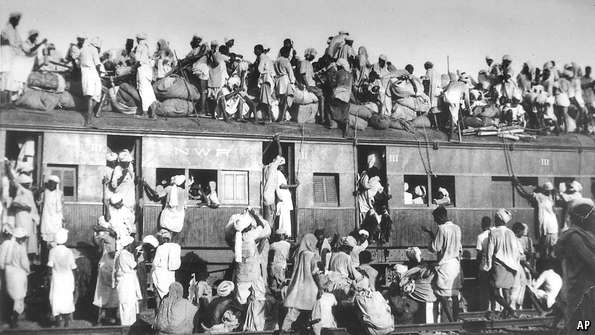

Off the rails

NEARLY 70 years ago the Indian subcontinent was divided. A fifth of the territory and 17.5% of the people formed Pakistan. The rest became independent India. Departing British colonial authorities rushed the split. The result was a bloody mess. Pakistan proved ungainly from the start, composed of two distant Muslim-majority areas, separated by 1,100 miles (1,770km) as the crow flies. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, its first ruler, moaned that his country was “maimed and moth eaten”.

Jinnah had been an unlikely figure to bring Pakistan into existence. A wealthy, anglophile lawyer with a Parsi wife, he had long resisted fervently mixing religion and politics, even as his more successful rival, Mohandas Gandhi, was happy to marry them together. Jinnah’s political triumph came only when he changed methods, stoking Muslim fears of a “Hindu Raj” in India. On August 11th 1947 he told an assembly crafting a new constitution that Pakistan was being born of necessity, as Muslims had “no other solution”.

In Dilip Hiro’s brisk and clear history of partition and its effects, “The Longest August”, evidence piles up of the great, long-lived cost of all this. He says that the “communal holocaust” resulted in the massacre of over half a million people, Hindus and Muslims in roughly equal number. Killings began apparently spontaneously, as members of rival religious groups settled old scores, and then escalated in a cycle of vengeance. Millions more were displaced; trudging refugees formed caravans that were more than 50 miles long. Relations between India and Pakistan were probably destined to be awful, but Pakistan made sure of it by starting an ill-judged war (the first of several), sending Pushtun fighters to invade Muslim-majority Kashmir. They botched the job, ensuring Kashmir’s accession to India. India’s repressive rule there has ensured that the dispute remains unresolved.

Neither country’s fate has been ideal, but India is easily more democratic, stable and better off. Mr Hiro’s focus is not on the larger country—a shame, because he might have emphasised how Muslims who stayed behind, and their descendants, face a brighter future than Pakistanis whose society is more intolerant and more violent. Instead his interest is in telling the successive missteps of Pakistan and its relations with its larger twin.

India under Jawaharlal Nehru enshrined constitutional rule. In Pakistan Jinnah’s early death, just 13 months after partition, left uncertainty. The army soon grabbed ever more power and public resources, justifying itself by talking up threats from India. Successive leaders, both civilian and military, used and encouraged Islamist extremists. Repression and further slaughter in East Pakistan led to the secession of that half of the country, with military help from India, in 1971.

Other wars, such as Pakistan’s reckless effort in 1999 to grab Kargil, a sliver of Indian Kashmir, have further poisoned cross-border relations. Islamist militants and terrorists in Pakistan, some backed by parts of the army, regularly attack Kashmir, other parts of India and Indian targets in Afghanistan. India, often clumsy and arrogant, has also been at fault, building alliances in Afghanistan that worry Pakistan, and allegedly helping separatists in Pakistan’s Balochistan province or talking of plans for invasion. The bitterness is not diminishing: Narendra Modi, the first Indian prime minister to be born after partition, appears more confrontational than his predecessors despite a friendly start last May, when Nawaz Sharif, Pakistan’s civilian leader, was invited to his inauguration.

Mr Hiro, born in Sindh before partition, has written a highly readable account of a complicated history. It first considers how partition came about, mostly through the personalities of Jinnah and Gandhi. He holds Gandhi, whose faith was “orthodox Hinduism”, and India’s Congress party more responsible than Muslim leaders for India’s split. But he is also damning of Jinnah, whom Gandhi called an “evil genius” and “a Hitler” for unleashing religious violence for political gain. The book goes on to explore the fates of both countries through their acquisition of nuclear weapons, border clashes and Bollywood. Others may delve deeper into who bears most blame for three-quarters of a century of strife. But Mr Hiro’s book has other virtues. A dispassionate chronological narrative, it is an excellent introduction to a bitterly contested topic.