Juneteenth

| Juneteenth or June 19th 1865 | |

|---|---|

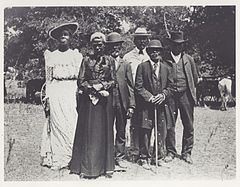

Juneteenth celebration in Austin, Texas, on June 19, 1900 | |

| Also called | Freedom Day or Emancipation Day |

| Observed by | Residents of the United States, especially African Americans |

| Type | Ethnic, historical |

| Significance | Emancipation of last remaining slaves in the United States |

| Observances | Exploration and celebration of African-American history and heritage |

| Date | June 19 |

| Next time | June 19, 2016 |

| Frequency | annual |

Juneteenth, also known as Juneteenth Independence Day, Freedom Day, or Emancipation Day, is a holiday in the United States that commemorates the announcement of the abolition of slavery in the U.S. state of Texas in June 1865, and more generally the emancipation of African-American slaves throughout the Confederate South. Celebrated on June 19, the term is a portmanteau of June and nineteenth,[1][2] and is recognized as a state holiday or special day of observance in most states.

The holiday is observed primarily in local celebrations. Traditions include public readings of the Emancipation Proclamation, singing traditional songs such as "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot" and "Lift Every Voice and Sing", and readings by noted African-American writers such as Ralph Ellison and Maya Angelou.[3] Celebrations may include parades, rodeos, street fairs, cookouts, family reunions, park parties, historical reenactments, or Miss Juneteenth contests.[4][self-published source]

Chris Moore

23 minutes agoJUNETEENTH or ignorance of Juneteenth reflects "Life, Liberty and Property," far more than "Pursuit of Happiness." The former slaveholder's...

Ecce Homo

23 minutes agoUnless schooling has changed an awful lot since my childhood, slavery is taught in history classes in a very matter-of-fact way. We were...

William Case

24 minutes agoSlavery lasted less two lifetimes in the United States. Counting from the Declaration of Independence, slavery endured for 89 years in only...