United Nations representative pushes Conservatives on First Nations

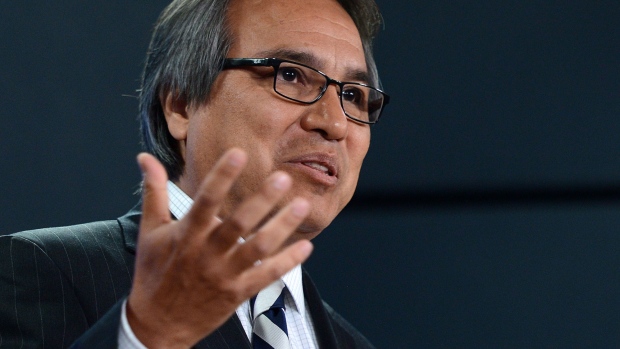

United Nations Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, James Anaya, holds a press conference at the National Press Theatre in Ottawa on October 15, 2013. (Sean Kilpatrick / THE CANADIAN PRESS)

OTTAWA -- A United Nations rapporteur is at a loss to explain how a prosperous and sophisticated country like Canada has come to have on its hands a First Nations human-rights problem that has reached "crisis proportions."

James Anaya's report picks a fight with the federal government on several fronts -- education, energy projects on reserves and missing or murdered aboriginal women, to name a few -- and is sure to amplify tensions between Canada's First Nations and a federal government they so thoroughly distrust.

"It is difficult to reconcile Canada's well-developed legal framework and general prosperity with the human rights problems faced by indigenous peoples in Canada that have reached crisis proportions in many respects," writes Anaya, the UN's special rapporteur on indigenous rights.

"Moreover, the relationship between the federal government and indigenous peoples is strained, perhaps even more so than when the previous special rapporteur visited Canada in 2003."

Aboriginal Affairs Minister Bernard Valcourt acknowledged more work needs to be done, but highlighted steps the government has taken to give First Nations the same access to safe housing, education and matrimonial rights as non-aboriginals.

"Our government is proud of the effective and incremental steps taken in partnership with aboriginal communities. We are committed to continuing to work with our partners to make significant progress in improving the lives of aboriginal people in Canada," Valcourt said in a statement.

"We will review the report carefully to determine how we can best address the recommendations."

Anaya, who spent nine days in Canada last year meeting with First Nations representatives and government officials, found appalling conditions on many reserves.

He identified shortfalls in First Nations education, housing and health, as well as the need for greater consultation with aboriginals on major energy projects, such as the Northern Gateway pipeline from Alberta to the British Columbia coast.

Anaya also added his voice to the chorus of those calling for a national inquiry into an estimated 1,200 cases of aboriginal women and girls who have been murdered or gone missing in the past 30 years.

The report comes on the heels of revelations from RCMP Commissioner Bob Paulson that police have compiled a list of 1,026 deaths and 160 missing-persons cases involving aboriginal women -- hundreds more than previously believed.

The Conservatives have so far resisted calls for a national inquiry, saying the issue has been studied enough and now is the time for action.

But Anaya said even though some steps have already been taken, an investigation "into the disturbing phenomenon of missing and murdered aboriginal women and girls" is still necessary.

"The federal government should undertake a comprehensive, nationwide inquiry into the issue of missing and murdered aboriginal woman and girls, organized in consultation with indigenous peoples," the report says.

Opposition parties seized the opportunity Monday to assail the way the federal Conservatives have handled the First Nations file.

"This report clearly articulated both the serious and persistent crisis in outcomes for indigenous people in this country, and that the steps taken by the Conservatives have not only failed to address this crisis, but have created a high level of distrust towards the federal government," Liberal MP Carolyn Bennett said in a statement.

An inquiry would go a long way towards restoring trust, said Bennett, a sentiment echoed by the NDP's Jean Crowder.

"Continuing to ignore calls for an inquiry into missing and murdered indigenous women only increases that distrust," Crowder said.

"People honestly don't understand why they continue to ignore what amounts to a public safety emergency."

Anaya's report comes at a pivotal moment in the relationship between the governing Conservatives and First Nations.

The Assembly of First Nations is in disarray after the sudden resignation of its national chief, Shawn Atleo. As a result, the government's proposed changes to First Nation education are in limbo until the assembly clarifies its stance.

Valcourt has defended Bill C-33, dubbed the First Nations Control of First Nations Education Act, saying it meets the five conditions outlined by the AFN and chiefs during a meeting in December.

A number of First Nations groups have criticized the legislation, saying it would strip away their rights and give the federal government too much control over the education of their children.

Meanwhile, a governing body within the Assembly of First Nations that has been inactive for a decade is being resurrected this week to deal with the fallout of Atleo's resignation and the Conservative legislation.

The assembly is also scheduled to hold a special chiefs' meeting on education later this week, followed by a chiefs' assembly in Ottawa on May 27. The assembly says it hopes the chief will adopt a "collective position" on the Conservative bill.