When your body betrays you

-A young woman’s Type 1 diabetes story

Something’s Not Right

In October 2016, Anika Lambert was a busy young woman. She was 20-years-old and balancing two stressful preoccupations: finishing off her final year of university while travelling around the country to collect and compile data for her job as a project coordinator. She expected to feel fatigued, but as the weeks dragged on, her exhaustion and malaise only seemed to worsen as she developed other troubling symptoms.

“I would wake up in the middle of the night or in the morning, and my mouth would be completely dry. No saliva, nothing at all,” Anika recalled, as we sat on the green and grey plastic picnic table under her uncle’s house. “I would be hungry, and then I would eat, but I wouldn’t feel satisfied. I started drinking excessive amounts of water [and] urinated often. I also started losing weight.”

Her work began to suffer. Some days, she would feel so tired that she would be physically incapable of staying up past midnight. Her mother urged her to go to the doctor, but she didn’t listen.

“I didn’t wanna spend money for a doctor to tell me to drink builders and rest,” she remembered thinking, “but it turned out to be more serious than that.”

All along and unbeknown to Anika, her body’s defence systems had turned against her pancreas, a knobbly organ located behind the stomach, which produces insulin. Her white blood cells had been attacking her Islets of Langerhans – the insulin-producing cells of the pancreas, thus destroying her body’s ability to use glucose or “sugar”. Our muscle cells cannot absorb the glucose they need from the blood on their own. They need assistance. Dotted along the cell’s surface membranes are special receptors that bind with insulin to act as a sort of glucose-exclusive gate. When this happens, the cells can absorb glucose to perform tasks like lifting a backpack, taking a jog or simply yawning. As her islets died off her body could no longer produce insulin. Her exhaustion, sickness, and insatiable hunger and thirst were signs that her body was not using the glucose it produced after digesting her food. Without insulin, the sugar just floated idly in her bloodstream. She was developing diabetes.

Misconceptions

When people think about diabetes, someone like Anika rarely comes to mind. We have all seen the Lyrica advertisements on television or may have a family member currently struggling with the disease. Anika’s own grandmother died due to diabetic complications almost two decades ago. Often, the stereotypical image of a person with diabetes is someone middle-aged or elderly or may or may not be overweight and sedentary. But Anika herself matches none of these stereotypes. She’s now 23-years-old, fit, healthy and several decades away from retirement.

However, what many people may not know is that there are two forms of diabetes. According to the American Diabetes Association, most diabetics have Type II diabetes, which often develops slowly and later in life as the body loses its ability to respond to insulin. Conversely, Anika has Type I or insulin-dependent diabetes: an autoimmune disease that develops when the body’s immune system has an adverse reaction to either insulin or the Islets of Langerhans themselves. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the symptoms of Type I diabetes can occur suddenly and without prior warning.

Researchers are not sure about what triggers the disease. Some assume that a random mutation in the pancreas causes it to produce a form of insulin that looks like an antigen, which acts as a red flag to the immune system that the body is being invaded by something dangerous like a harmful germ or a deadly toxin. The white blood cells follow this trail of mutated insulin to the pancreas and destroy the islets in a misguided attempt to protect the body from further harm. Another theory proposes that a childhood enterovirus infection, which may show few if any symptoms, can trigger an autoimmune response against the pancreas.

Regardless of how the disease starts, the result is disastrous. Without the ability to absorb

glucose from the blood, the muscle cells begin to starve while glucose continues to accumulate to dangerous levels in the bloodstream. It can be said that Type I diabetes is literally “starvation among plenty”.

Crisis

Blurb: ‘Like, how do you just pop up with diabetes all of a sudden?’

“I felt like I was not going to make it home,” Anika recounted, “I was in the car praying that I would make it home alive because I felt like I was going to pass out.”

On January 6, 2017, Anika attended her father’s Twelfth Night party on the East Bank, about an hour’s drive away from her home in Beterverwagting. Her symptoms, particularly her incessant thirst, had been getting worse. There was no water at the party, oddly enough, only sugary drinks and alcohol. She kept on guzzling the sweet drinks, hoping that they would quench her thirst, but by the end of the night, she began to feel worse. She said her goodbyes and began the long agonized drive home.

“Somehow, I made it home and drank maybe a half-gallon of water [and] was up the whole night peeing. I remember thinking to myself, ‘Anika, you can’t ignore this any longer. Something is really wrong’.”

The next morning, she finally went to the hospital, googling her symptoms on her phone along the way and getting the first inkling that she may have diabetes. Her first reaction was denial; she was too young.

“I tested my sugar a couple months ago, and I was totally fine. Like, how do you just pop up with diabetes all of a sudden?” she remembered asking herself.

When she arrived at the hospital and the doctor tested her blood sugar levels, it was over 300mg/dl and rising rapidly. At its peak, it was almost 500mg/dl – more than three and a half times the recommended upper limit for a healthy adult. Her astonished doctor rushed her to the emergency room, fearing that she may slip into a coma as her blood sugar continued to climb. She was admitted to the hospital soon after, where she could be monitored and counselled about her new condition. Her world had changed in just 24 hours. There would be new limitations imposed upon her life and she would need to learn how to take care of herself within those boundaries.

Catharsis

Anika went through a rough adjustment period after her time in hospital. As her body adjusted to her injectable insulin and medications, her blood sugar level would swing up and down wildly, leaving her feeling weak or sick. To make matters worse, she had classes to attend to, exams to write and projects to complete in a little more than a week after her hospitalisation. Plus, she had the final semester of her fourth year ahead of her. Nevertheless, she persevered. She battled through her illness, wrote her exams and got an extension on her projects. That November, she graduated from university and now, two years later, she is working full time and enjoying a somewhat normal life.

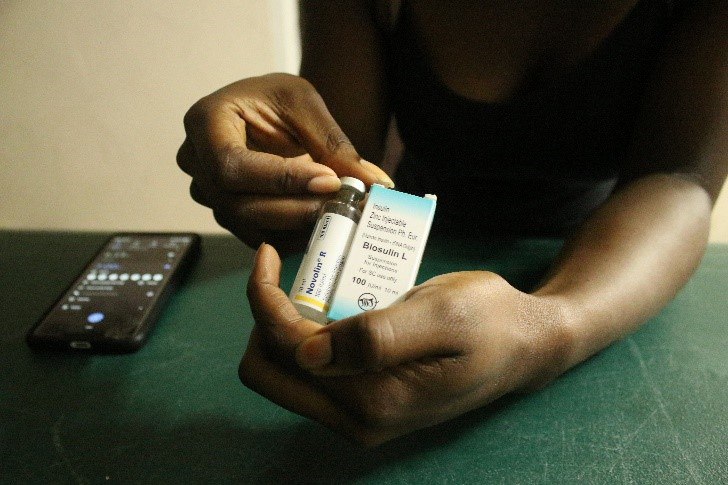

Anika showing her personal alarm system for her insulin schedule

There are limitations, however. Sometimes her socials are cut short when she needs to run home to take her insulin, which needs to be refrigerated constantly. She needs to keep glucose pills or sweets near her bed in case her blood sugar drops too low. She could live without being sick, she said. She hates the limitations, the fuss and the expense of medications, the availability of which are not always guaranteed.

Regardless, she is thankful for her family and friends who form a strong support system around her, even if their fussing over her health and wellness gets annoying occasionally. Her diabetes is under control with her daily insulin therapy and has been for over a year now. But most importantly, though, she is alive and doing well.