I am hoping one day there will be a black queen in England, now that will be something to write about ![]()

‘I am who I am’: Kamala Harris, daughter of Indian and Jamaican immigrants, defines herself simply as ‘American’

By Kevin Sullivan, Feb. 2, 2019 at 4:26 p.m. MST, Source -

Sen. Kamala D. Harris (D-Calif.), center, sings the Alpha Kappa Alpha hymn at the sorority’s annual “Pink Ice Gala” on Jan. 25 in Columbia, S.C. (Elijah Nouvelage/Bloomberg News)

They had always assumed Harris was African American, and so did most of the 60 or 70 Indian American community leaders at the event, many of whom asked Puri and Punian why they had been invited.

“At least half of them didn’t know she was Indian,” said Punian, a business executive and political activist.

Harris, 54, now a U.S. senator and 2020 Democratic presidential candidate, would be several firsts in the White House: the first woman, the first African American woman, the first Indian American and the first Asian American. The daughter of two immigrants — her father came from Jamaica — she would also be the second biracial president, after Barack Obama.

Obama’s soul-searching quest to explore his identity, as the son of a white mother from Kansas and a Kenyan father who was largely absent from his life, was well-documented in his autobiography.

But when asked, in an interview, if she had wrestled with similar introspection about race, ethnicity and identity, Harris didn’t hesitate:

“No,” she said flatly.

President Barack Obama walks along the tarmac with California Attorney General Kamala D. Harris, center, and Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom, left, after Obama’s arrival via Air Force One in San Francisco in February 2011. (Carolyn Kaster/AP)

President Barack Obama walks along the tarmac with California Attorney General Kamala D. Harris, center, and Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom, left, after Obama’s arrival via Air Force One in San Francisco in February 2011. (Carolyn Kaster/AP)

Harris stressed that she doesn’t compare herself to Obama, and she prefers that others don’t, either. She wants to be measured on her own merits.

She said she has not spent much time dwelling on how to categorize herself.

“So much so,” she said, “that when I first ran for office that was one of the things that I struggled with, which is that you are forced through that process to define yourself in a way that you fit neatly into the compartment that other people have created.

“My point was: I am who I am. I’m good with it. You might need to figure it out, but I’m fine with it,” she said.

Harris’s background in many ways embodies the culturally fluid, racially blended society that is second-nature in California’s Bay Area and is increasingly common across the United States.

She calls herself simply “an American,” and said she has been fully comfortable with her identity from an early age. She credits that largely to a Hindu immigrant single mom who adopted black culture and immersed her daughters in it. Harris grew up embracing her Indian culture, but living a proudly African American life.

Shyamala Gopalan holds a copy of the Bill of Rights as her daughter Kamala D. Harris, right, is sworn in as San Francisco’s district attorney by California Supreme Court Chief Justice Ronald M. George on Jan. 8, 2004, in San Francisco. (George Nikitin/AP)

Shyamala Gopalan holds a copy of the Bill of Rights as her daughter Kamala D. Harris, right, is sworn in as San Francisco’s district attorney by California Supreme Court Chief Justice Ronald M. George on Jan. 8, 2004, in San Francisco. (George Nikitin/AP)

“My mother understood very well that she was raising two black daughters,” Harris writes in her recently published autobiography, “The Truths We Hold.” “She knew that her adopted homeland would see Maya and me as black girls, and she was determined to make sure we would grow into confident, proud black women.”

Her mother, Shyamala Gopalan, was keenly attracted to the civil rights movement and the African American culture of her new home in the 1960s and ’70s. At first, she marched and protested with her black husband, then alone or with the girls after they divorced when Harris was very young.

She brought her daughters home to India for visits, she cooked Indian food for them, and the girls often wore Indian jewelry. But Harris worshiped at an African American church, went to a preschool with posters of Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman on the wall, attended civil rights marches in a stroller, and was bused with other black kids to an elementary school in a wealthier white neighborhood. When it was time for college, she moved across the country to Washington to attend the historically black Howard University.

“Her Indian culture, she held on to that,” said Sharon McGaffie, 67, an African American woman who has known Harris and her sister, Maya, since they were toddlers living in Berkeley, Calif. “But I think they grew up as black children who are now black women. There’s no question about it.”

Kamala Harris, left, stands with John McGaffie, center, his daughter Kenya, front center, her mother Shyamala Gopalan and her sister Maya outside the McGaffie home in Berkeley, Calif., in the 1970s. (Courtesy of Sharon McGaffie)

Kamala Harris, left, stands with John McGaffie, center, his daughter Kenya, front center, her mother Shyamala Gopalan and her sister Maya outside the McGaffie home in Berkeley, Calif., in the 1970s. (Courtesy of Sharon McGaffie)

Maya Harris, John and Sharon McGaffie, and California Attorney General Kamala D. Harris in August 2013. (Courtesy of Sharon McGaffie)

Maya Harris, John and Sharon McGaffie, and California Attorney General Kamala D. Harris in August 2013. (Courtesy of Sharon McGaffie)

As Harris’s political profile has risen outside her home region, she will face pressure to discuss her heritage from a broader electorate seeking to fully understand her and politically connected Indian Americans who feel she has not previously put as much focus on her South Asian roots.

In her years in the public eye — seven years as San Francisco district attorney and six years at California’s attorney general before her election to the Senate in 2016 — Harris has tended to stress issues over her personal biography.

Harris, in the interview, said that was because, “It’s not about me. It’s about the people I represent.”

She said political campaigns, especially for president, require candidates to explain their background so voters “can figure out why you do what you do.” So while she “was raised not to talk about myself,” she said that is why she wrote her book to lay out the details of her heritage and career.

“I appreciate that there is that desire that people have to have context, and I want to give people context,” she said.

Harris hasn’t tried to shape perceptions of her identity as much as she has simply accepted that most people see her as black, said Robert C. Smith, a recently retired professor of political science at San Francisco State University who specializes in African American politics.

“She has not used it politically,” Smith said. “She has not avoided it, she has just kind of said it and moved on: ‘I’m this, I’m this, I’m that, now let’s move on’ to talk about the death penalty or whatever is the issue of the day.”

Smith said Harris’s “blackness was never ambiguous” and she didn’t feel the need to trumpet it.

Her lack of public focus on her heritage has left many people, even in her home state, unaware of her multiracial background. Most people assume she is African American, and even some friends didn’t know that she was also Indian.

“I had no idea,” said Matthew Davis, a San Francisco lawyer and classmate of Harris’s at the University of California, Hastings College of the Law, where they graduated in 1989.

“Even though we were good friends, I never really heard her talk too much about her personal life,” said Davis, who also worked with Harris in the San Francisco city attorney’s office before she was elected district attorney.

It was only when she was sworn in as district attorney in 2004, 15 years after they graduated from law school, that Davis learned Harris was half Indian.

“She introduced me to her mother, and that was the first time I knew,” Davis said. “It was a sense of pride for her, but I didn’t get the sense that it was the way she defined herself.”

A crowds listens to Sen. Kamala D. Harris (D-Calif.) speak at the launch of her presidential campaign at a rally Jan. 27 in Oakland, her hometown. (Elijah Nouvelage/Reuters)

Even now, Harris still doesn’t seem fully at ease discussing her personal heritage.

In her first campaign stop after announcing her bid for president on “Good Morning America” on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Harris appeared on her old Howard campus to take questions.

“You’re African American, but you’re also Indian American,” a reporter said.

“Indeed,” she replied.

“How do you describe yourself?”

“Did you read my book? How do I describe myself? I describe myself as a proud American.”

She said it with a smile, but with an “end-of-conversation” firmness.

Leah Williams, a San Francisco lawyer who has been friends with Harris since the early 1990s, said Harris inherited a “strong sense of self” from her mother, who raised two daughters as a single immigrant mom.

“She’s not a person who doesn’t contemplate herself or her identity,” Williams said in an interview. “But there are just people who get up in the morning and look in the mirror and know who they are.”

Vice President Joe Biden, center, ducks down so all of the family of Sen. Kamala D. Harris (D-Calif.), second from right, can be seen for a group photo during a mock swearing-in ceremony in the Old Senate Chamber on Capitol Hill in 2017. (Alex Brandon/AP)

Vice President Joe Biden, center, ducks down so all of the family of Sen. Kamala D. Harris (D-Calif.), second from right, can be seen for a group photo during a mock swearing-in ceremony in the Old Senate Chamber on Capitol Hill in 2017. (Alex Brandon/AP)

Williams, who took her children to Washington to attend Harris’s Senate swearing-in ceremony in 2017, said Harris was “centered and anchored” because she grew up in a house with two other strong women who were role models.

“Growing up, they could all look at each other and see themselves in each other,” Williams said.

Harris agreed that her upbringing was filled with “pride and nurturing” that gave her a solid grounding.

“I’m no different than anybody else,” she said. “I’m not suggesting that I don’t have the doubts and whatever that any normal person has. But . . . I don’t have any doubts about who I am ethnically or racially.”

Harris has often spoken of her mother, a Tamil from Chennai in southeast India, as her inspiration, and she writes about it extensively in her book.

Gopalan graduated from college in India at 19, then moved to California in 1959 and earned a PhD from the University of California at Berkeley. There, she met and married Donald J. Harris, who is now an emeritus professor of economics at Stanford University. The elder Harris did not respond to a request for comment.

After their divorce, Harris visited her father’s family in Jamaica and stayed in touch with him. But she credited her mother, a noted cancer researcher and civil rights activist who died in 2009, with being “most responsible for shaping us into the women we would become.”

On her visits to India as a child, Harris was deeply influenced by her grandfather, a high-ranking government official who had fought for Indian independence. But while she had a “strong awareness and appreciation for Indian culture,” she writes, her mother raised her in an African American world.

“From almost the moment she arrived from India, she chose and was welcomed to and enveloped in the black community,” Harris writes. “It was the foundation of her new American life.”

Sharon McGaffie’s mother, Regina Shelton, ran the preschool that Harris and her sister attended. Because Harris’s mother traveled often for her work as a cancer scientist, the girls would regularly stay over at McGaffie’s house, two doors down on a quiet street in Berkeley. Shelton became like a mother to Harris’s mother, and grandmother to Harris.

McGaffie said the Harris girls would regularly accompany her family to the Twenty Third Avenue Church of God in Oakland, Calif., an African American protestant congregation. Their mother eagerly encouraged them to go but did not attend herself, McGaffie said.

When Harris was sworn into office as AG and senator, she did so with her hand on the Bible that Shelton carried with her to church every Sunday.

“She has always been engaged in African American politics, community struggles, community organizations, and life,” said Karen V. Clopton, a lawyer and former judge in San Francisco who has been a friend of Harris’s for more than two decades.

Sen. Kamala D. Harris (D-Calif.) speaks to Mara Peoples and Amos Jackson III after announcing her presidential candidacy at her alma mater, Howard University, in Washington on Jan. 21. (Al Drago/Getty Images)

Sen. Kamala D. Harris (D-Calif.) speaks to Mara Peoples and Amos Jackson III after announcing her presidential candidacy at her alma mater, Howard University, in Washington on Jan. 21. (Al Drago/Getty Images)

Harris’s college choice marked a notable contrast from the rest of her family. Her parents both earned PhDs from UC Berkeley, and her sister went to UC Berkeley and Stanford Law School. Harris opted for Howard, one of the country’s most prestigious historically black schools. She said that was largely because her hero, trailblazing lawyer and Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, went there.

“As a black woman, it gave her a real opportunity to be enveloped in that part of who she is,” said her friend Leah Williams. “She holds that experience close to her heart.”

Four days after addressing reporters at Howard, Harris traveled to South Carolina, a key early primary state with a large African American electorate. She spoke at the annual “Pink Ice Gala” hosted by her sorority, Alpha Kappa Alpha, the nation’s oldest black sorority, which has a network of 300,000 members.

In her official campaign kickoff speech in Oakland last weekend, Harris stood before 20,000 people and spoke of some of her African American heroes — faces she grew up with on Shelton’s walls.

“When abolitionists spoke out and civil rights workers marched, their oppressors said they were dividing the races and violating the word of God,” she said. “But Fredrick Douglass said it best and Harriet Tubman and Dr. King knew. To love the religion of Jesus is to hate the religion of the slave master.”

Asked in The Washington Post interview how her African American background has influenced her, Harris said, “It’s kind of like asking how did eating food shape who I am today.”

“It affects everything about who I am,” she said. “Growing up as a black person in America made me aware of certain things that, maybe if you didn’t grow up black in America, you wouldn’t be aware of.”

Asked for an example, she said, “Racism.”

“I grew up in a hot spot of the civil rights movement,” she said. “But that civil rights movement involved blacks, it involved Jews, it involved Asians, it involved Chicanos, it involved a multitude of people who were aware that there were laws that were not equally applied to all people.”

A sizable crowd attends at the rally on Jan. 27 in Oakland, Calif. (Tony Avelar/AP)

As Harris has become a prominent figure in state and national politics, many Indian Americans are thrilled — and a little surprised to learn of her Indian background.

“It’s only been in the last year or so that she’s really come out and embraced it,” said Aziz Haniffa, executive editor of India Abroad, the oldest and largest South Asian newspaper in the United States.

Harris has never made a secret of her Indian heritage, and she has fought on behalf of issues of importance to most Indians, including immigration reform. She has appeared at Indian American gatherings throughout her career.

Indian American publications proudly use her Indian first name, which means “lotus flower,” along with her middle name, Devi, the Sanskrit word for “goddess,” which Harris generally doesn’t use.

In a 2009 interview with India Abroad, Harris said her Indian background “has had a great deal of influence on what I do today and who I am.” She told the interviewer her African American and Indian heritage “are of equal weight in terms of who I am.”

She continued: “We have to stop seeing issues and people through a plate-glass window as though we were one-dimensional. Instead, we have to see that most people exist through a prism and they are a sum of many factors.”

Shekar Narasimhan, chairman and founder of the AAPI Victory Fund, a national super PAC founded in 2015 that focuses on building the political power of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, said Harris in the past year has done several high-profile speeches and events with Indian American groups that have helped to raise her profile.

“I’m so glad she has discovered her Indian-ness,” Narasimhan said with a laugh. “It’s sudden, but I absolutely love that it’s happening. It’s not something she has exhibited over the years.”

Sen. Kamala D. Harris (D-Calif.) says she has not spent much time dwelling on how to categorize herself. “We have to stop seeing issues and people through a plate-glass window as though we were one-dimensional. Instead, we have to see that most people exist through a prism and they are a sum of many factors,” she says. (Noah Berger/AFP/Getty Images)

M.R. Rangaswami, a Silicon Valley entrepreneur, investor and philanthropist, said Harris’s story parallels the rising influence of the U.S. Indian community.

Rangaswami said Indians represent about 1 percent of the population, and now have about 1 percent representation in Congress, with four members of the House of Representatives and one senator.

“My advice to Kamala would be: ‘You’ve got a great story. You should tell it,’ ” he said. “As the community has come of age, there is a yearning for successful role models, and she totally fits that model.”

In the Post interview, Harris said she disagreed with the perception that she has not stressed her Indian background, saying she had “been focused on the Indian community my entire life.”

She said the view that she embraced it wholeheartedly only more recently was “a matter of what people are aware of and what the press has focused on.”

She pointed, for example, to her advocacy as early as 2001, after the 9/11 attacks, when South Asians became the targets of abuse and violence. “I was very active in fighting to make sure that the community was not the subject of hate and bias and ill treatment,” she said.

“I grew up with a great deal of pride and understanding about my Indian heritage and culture,” she said.

In their San Francisco home, where they hosted the 2010 fundraiser, Puri and Punian said they were enthusiastic about Harris. Puri, a Silicon Valley software executive, and Punian, a finance executive, have helped introduce Harris around Silicon Valley. They are co-founders of the Democracy Labs, an organization that supports progressive campaigns.

Puri said Harris’s multicultural background appeals to many people.

“It’s like a Rorschach test,” he said. “Every person can interpret her differently.”

Chelsea Janes contributed to this report.

@Amral posted:I am hoping one day there will be a black queen in England, now that will be something to write about

Was Queen Charlotte Black? Here’s what we know.

‘Bridgerton,’ the new Netflix series from Shonda Rhimes, has renewed interest in the British royal family’s possible African ancestry

By DeNeen L. Brown, Dec. 27, 2020 at 8:14 a.m. MST, Source - https://www.washingtonpost.com...rlotte-black-royals/

Golda Rosheuvel as Queen Charlotte in “Bridgerton.” (Liam Daniel/Netflix)

Golda Rosheuvel as Queen Charlotte in “Bridgerton.” (Liam Daniel/Netflix)

Excellent point. But the queen in question is Charlotte, who married King George III (yes, that King George) six hours after arriving in London and meeting him for the first time Sept. 8, 1761. Some historians do believe that she was Britain’s first Black queen and that her descendants, including Queen Victoria and Queen Elizabeth II, have African ancestry.

Charlotte, who was born May 19, 1744, was the youngest daughter of Duke Carl Ludwig Friedrich of Mecklenburg-Strelitz and Princess Elisabeth Albertine of Saxe-Hildburghausen.

She was a 17-year-old German princess when she traveled to England to wed George, who later went to war with his American colonies and lost badly.

Historian Mario De Valdes y Cocom argues that Charlotte was directly descended from a Black branch of the Portuguese royal family: Alfonso III and his concubine, Ouruana, a Black Moor.

In the 13th century, “Alfonso III of Portugal conquered a little town named Faro from the Moors,” Valdes, a researcher on the 1996 Frontline PBS documentary “Secret Daughter,” told The Washington Post in 2018. “He demanded [the governor’s] daughter as a paramour. He had three children with her.”

According to Valdes, one of their sons, Martín Alfonso, married into the noble de Sousa family, which also had Black ancestry. Thus, Charlotte had African blood from both families.

Valdes, who grew up in Belize, began researching Charlotte’s African ancestry in 1967 after he moved to Boston.

He discovered that the royal physician, Baron Christian Friedrich Stockmar, had described Charlotte as “small and crooked, with a true mulatto face.” He also found other descriptions, including Sir Walter Scott writing that she was “ill-colored.” And a prime minister who once wrote of Queen Charlotte: “Her nose is too wide and her lips too thick.

”In several British colonies, Charlotte was often honored by Blacks who were convinced from her portraits and likeness on coins that she had African ancestry.

Valdes became fascinated by official portraits of Charlotte in which some of her features, he said, were visibly African.

“I started a systematic genealogical search,” Valdes said, which is how he traced her ancestry back to the mixed-race branch of the Portuguese royal family.

In a portrait by Sir Allan Ramsay, Charlotte is featured wearing a pink silk gown and holding two children. Her dark brown hair is piled high.

Ramsay, Valdes said, was an abolitionist married to the niece of Lord Mansfield, the judge who ruled in 1772 that slavery should be abolished in the British Empire.

In 1999, the London Sunday Times published an article with the headline: “REVEALED: THE QUEEN’S BLACK ANCESTORS.”

“The connection had been rumored but never proved,” the Times wrote. “The royal family has hidden credentials that make its members appropriate leaders of Britain’s multicultural society. It has black and mixed-raced royal ancestors who have never been publicly acknowledged. An American genealogist has established that Queen Charlotte, the wife of George III, was directly descended from the illegitimate son of an African mistress in the Portuguese royal house.”

After the Times story, the Boston Globe hailed Valdes’s research as groundbreaking. Charlotte passed on her mixed-race heritage to her granddaughter, Queen Victoria, and to Britain’s present-day monarch, Queen Elizabeth II.

Some scholars in England dismissed the evidence as weak — and beside the point.

“It really is so remote,” the David Williamson, former co-editor of Debrett’s Peerage, the guide to Britain’s barons, dukes and duchesses, marquises and other titled people, told the Globe. “In any case, all European royal families somewhere are linked to the kings of Castile. There is a lot of Moorish blood in the Portuguese royal family and it has diffused over the rest of Europe. The question is, who cares?”

Charlotte’s ancestry became the subject of public fascination when Britain’s Prince Harry married American actress Meghan Markle, whose mother is Black and whose father is White. Some people hailed her as Britain’s first mixed-race royal, prompting a reexamination of Queen Charlotte’s heritage.

Now “Bridgerton” and Rhimes are doing it again.

So who was Queen Charlotte? She spoke no English when she arrived in London after a difficult journey by sea.

The teenage princess was introduced to the 22-year-old king and “threw herself at his feet,” according to the book “A Royal Experiment: The Private Life of King George III” by Janice Hadlow. The two were married just six hours later.

On Aug. 12, 1762, she gave birth to the couple’s first child, the future King George IV, according to Buckingham Palace. Fourteen more children followed.

The royal couple’s official residence was St. James Palace. “But the King had recently purchased a nearby property, Buckingham House,” according to the Royal Encyclopaedia. “In 1762 The King and Queen moved into this new house, making it Buckingham Palace. Charlotte loved it — 14 of her children were born there, and it came to be known as ‘The Queen’s House.’ ”

Charlotte was an amateur botanist and a connoisseur of music. She especially liked German composers, including Handel. But her long marriage had an unhappy ending when the king began to suffer bouts of mental illness.

“After the onset of George III’s permanent madness in 1811,” according to Buckingham Palace, “The Prince of Wales became Regent, but Charlotte remained her husband’s guardian until her death in 1818.”

Africans in India: Pictures that Speak of a Forgotten History

An exhibition on Africans in India, highlighting the long history of African communities in India, opens on March 21.

Jahnavi Sen, Politics, 20/Mar/2016, https://thewire.in/politics/af...-a-forgotten-history

Sultan Muhammad Adil Shah of Bijapur and African courtiers, ca, 1640. Credit: The British Library Board

Sultan Muhammad Adil Shah of Bijapur and African courtiers, ca, 1640. Credit: The British Library Board

India and Africa have a shared history that runs deeper than is often realised. Trade between the regions goes back centuries – 4th century CE Ethiopian (Aksumite) coins have been found in southern India. Several African groups, particularly Muslims from east Africa, came to India as slaves and traders. On settling down in the country, they played important roles in the history of the region.

Forgotten histories

Unlike slave experiences in other parts of the world, enslaved Africans in India were able to assert themselves and attain military and political authority in their new homeland.

One of the most famous slave-turned-generals was Malik Ambar, an Ethiopian born guerrilla leader who went on to hold a prominent position in the Ahmadnagar Sultanate in west India in the 17th century. In spite of Ambar’s important role, he is a near forgotten chapter of history. Like Ambar, several other enslaved Africans rose to positions of power and prestige.

Ikhlas Khan, African prime minister of Bijapur, c. 1650, Credit: Johnson Album 26, no. 19, British Library. Public Domain.

“Free African traders, sailors, and skilled artisans were part of the movement of people across the India Ocean. Later on, captives were brought by the Arabs, the Portuguese and Indians”, Sylviane Diouf, director of the Lapidus Center for the Historical Analysis of Transatlantic Slavery in New York, told The Wire. “The people who became ‘elite slaves’ came mostly from the countries that today are Eritrea, Ethiopia and Sudan. The Portuguese brought in men and women from Mozambique. Later years also saw the arrival of people from Tanzania and adjacent countries.”

Africans in India were known as either Habshi or Sidi to denote their African origins. Even after centuries of mixing with local populations, the name Sidi remains for their descendants.

Contemporary situation

Sidis today number in the tens of thousands, and are found primarily in Karnataka, Gujarat and Andhra Pradesh. A majority of them are Muslims, with a few Christians and Hindus. In spite of their historical prominence and affluence, Sidi communities today are often marginalised with little access to education. A majority of the Indian population is unaware of their existence and roots. They are classified as a Scheduled Tribe in parts of Gujarat and Karnataka.

African eunuch (3rd from left) and African queen Yasmin (2nd from right) at the court of Wajid Ali Shah. Royal Collection Trust / © Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

Though they are now far removed from their African origins and have spent centuries with other populations speaking local languages, they have retained some of their musical and dance traditions.

In contemporary times, Africans from different parts of the continent continue to come to India. Higher education is one of the peak draws, since Indian universities are known for their quality, and are also inexpensive when compared to their counterparts in Europe or North America. For those from English-speaking African countries, the language of much of Indian higher education is an additional positive.

However, assimilation is not easy. African students often face racism and discrimination when looking for housing, from their fellow students, and also in their daily lives in India. The recent event in Bangalore involving the mob assault of a Tanzanian student and her friends, and the burning of their car, was a stark example of just how ugly racism in India can get.

On the political front, relations between India and African countries continue to grow. The India-Africa Summit is now three summits old. Whether strategic diplomatic relations and increased Indian investment in Africa will have any impact whatsoever on Indian social perceptions of Africa and Africans, however, remains to be seen.

Africans in India exhibition

In order to highlight the achievements and retrace the lives of prominent Africans who settled down in India, the Schomburg Centre for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library created the ‘Africans in India: From Slaves to Generals’ exhibition in collaboration with the United Nations ‘Remembering Slavery’ programme. The exhibition is designed and co-curated by Sylviane Diouf and Kenneth X. Robbins, art collector and expert in Indian art.

Through historic paintings and photographs, the exhibition looks at these forgotten histories in order to give them the recognition they deserve. The UN Information Centre, in collaboration with the South Asian University, Delhi and the Department of African Studies, Delhi University, is hosting this exhibition in New Delhi over the last ten days of March.

“The success [of Africans in India] is theirs, but also testimony to the open-mindedness of a society in which they were a small ethnic and original minority, originally of low status”, the curators say in an introduction to the exhibits. Whether a similar open-mindedness would be found in today’s India is a question that begs discussion.

Speaking to The Wire, Diouf described the contents and context of the exhibition. Excerpts:

The historical African diaspora in India is rarely discussed. What is the idea behind this exhibition and what is it trying to highlight?

The idea was to show the diversity of the African diaspora in terms of geography and history. Few people know that there is an African diaspora in the east, the vast majority think only of the Atlantic world. There is also a diversity of experiences within slavery. I started with a digital exhibition: The African Diaspora in the Indian Ocean World, which presents the history of Africans in Arabia, Oman, Yemen, Iraq, Iran, India, Sri Lanka, etc. The Indian story was so unique that it I thought it had to be the focus of a physical exhibition.

What was it that resulted in enslaved Africans in India rising in the ranks?

Due to Islamic laws, enslaved Africans had greater social mobility than was the case in the Americas. In the Islamic world, contrary to what happened in the West, bondage and “race” were not linked; in addition Africans were regarded as exceptional warriors. These soldiers could rise through the ranks and become “elite slaves,” amassing wealth and power. Elite slavery was often found in unstable areas due to struggles between factions and where hereditary authority was weak.

India had an abundance of local people to perform hard labor, so the Africans and other foreign slaves were mostly employed in specialised jobs as domestic workers in wealthy households, in the royal courts and in the armed forces. Rulers considered Africans reliable because they were foreigners without clan or caste connections to the local population. Slave soldiers, guards and bodyguards were routinely freed after a few years of service, but even when they were enslaved, many were promoted as court officials, administrators and army commanders. Enslaved or free, they were frequently at the centre of court disputes and sometimes seized power for themselves.

African groups settled in different parts of India. Were they equally successful in different parts?

The difference in success was not linked to the place but to the time period. The elite phenomenon was limited in time. Africans who arrived in the mid-1800s and later occupied lower positions at the courts. Those brought through the Portuguese slave trade, whatever the time period, were never allowed the same opportunities. Many fled to the forests or took refuge at the Muslim courts.

What is the time period this exhibition covers? Is there a change in the artists’ gaze on the African-Indian population over this period?

From the 1400s with paintings, to 1930 with photographs of the enthronement of Sidi Haidar Khan, the Nawab of Sachin, whose family founded one of two African dynasties in India (the other being Janjira). But the main periods covered are the 1600s and 1700s. We don’t notice any change in terms of how people were represented.

The ‘Africans in India: From Slaves to Generals’ exhibition opens at 4 pm on 21 March, and will be showing daily from 11 am to 5 pm at the South Asian University Gallery, Akbar Bhavan, Chanakyapuri, New Delhi.

Dese fing Ns juss wont stay hoam! Dey alows demsels tuh be kapture jess fuh free travel an board! Lyk mih fadder, de cheep plick! Well nat board in hiz case!

Seriously,DG! I had a photo of a beautiful jet black African girl I had downloaded from Facebook, but a criminal hacker removed it! Fing beauty to fing die for! Had everything, looks, body with a just right rear end with no need for any pillow for fing! I'll try to find it! Oh, Gawd! Ah moarn de loss!

30 Reasons to Thank a Black Person

by: Jennifer Shrum, Posted: / Updated:

Plenty would not exist were it not for black pioneers; here’s a very small glimpse at what modern day inventions came from the African American community.

1. Automatic Gear Shift

Richard Spikes – Driving up a steep hill got a whole lot easier in 1932, thanks to this guy.

2. America’s First Clock

Benjamin Banneker – He was a farmer, mathematician, astronomer, land surveyor, and the subject of a Stevie Wonder song.

3. Automatic Elevator Doors

Alexander Miles – We’ve all gotten the elevator door hug and we all owe this man.

4. Blimp

John Pickering – His was the first blimp to have an electric motor and directional controls. Goodyear better have this man’s picture in their lobby.

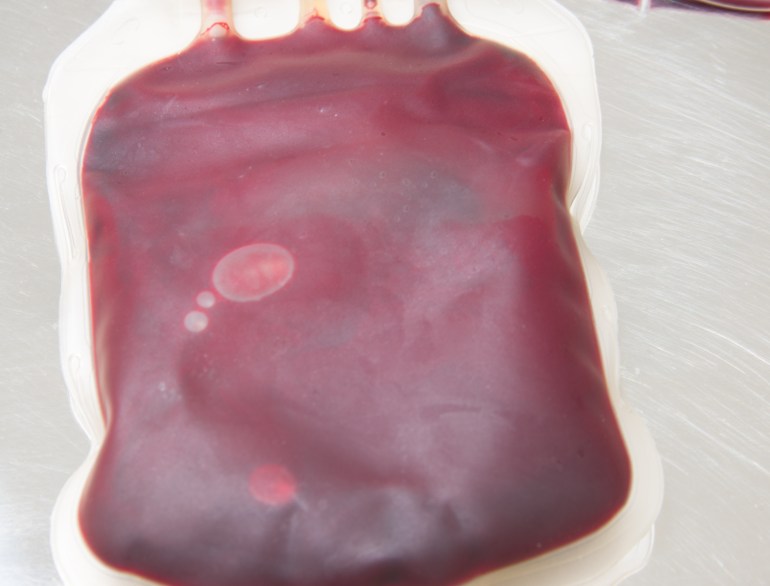

5. Blood Bank

Dr. Charles Drew – For his invention of a method of separating and storing plasma, allowing it to be dehydrated and banked for later use, Dr. Drew was the first black person awarded a doctorate at Columbia University.

6. Clothes Dryer

George T. Sampson – Giving laundry baskets a greater sense of purpose since 1892.

7. Dust Pan

Lloyd P. Ray – Mr. Ray patented the reason we have far fewer backaches.

8. Electric Lamp

Lewis Latimer – He also invented the carbon filament inside light bulbs.

9. Folding Chair

John Purdy – With patent partner James R. Sadgwar, Purdy made taking a chair with you purdy easy. Get it?

10. Gas Heating Furnace

Alice H. Parker – Forever changing the way we stay warm in the winter.

11. Gas Mask

Garret Morgan – It all started when this guy rescued trapped miners wearing a hood to protect his eyes from smoke and had tubes leading to the floor to draw clean air.

12. Golf Tee

Dr. George Grant – They say he was an avid golfer, but not a great one. Hopefully his patent improved his game.

13. Home Security System

Marie Van Brittan Brown – And television has been part of home security ever since.

14. Ice Cream Scooper

Alfred L. Cralle – You’ve been screaming, I’ve been screaming, we’ve all been screaming for this since 1897.

15. Ironing Board

Sarah Boone – The reason we no longer iron across a piece of wood balanced on two chairs.

16. Lawn Mower

John Albert Burr – The lawnmower’s best makeover ever brought better traction, rotary blades, and allowed cutting closer to buildings.

17. Lawn Sprinkler

Joseph A. Smith – We should honor this man for helping with Father’s Day ideas every year.

18. Mail Box

Phillip Downing – Before this invention, people had to make a long trip to the Post Office to mail a letter.

19. Modern Lock

Washington Martin – His patent was an improvement on the 4,000-year-old Chinese bolt.

20. Modern Toilet

Thomas Elkins – He influenced several major patents, but it’s this one we appreciate most (not to knock the multi-purpose table or refrigerators for dead bodies).

21. Mop

Thomas W. Stewart – He’s kept us off our hands and knees since 1893.

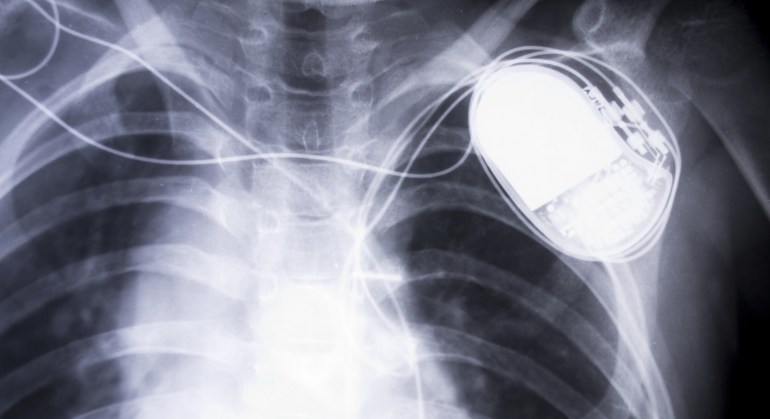

22. Pacemaker

Otis Boykin – On top of this lifesaving invention, he was born in Dallas, Texas. Double. Greatness.

23. Portable Pencil Sharpener

John Lee Love – A carpenter clever with names for his inventions, calling this one the ‘Love Sharpener.’

24. Potato Chips

George Crum – You have to love that his last name is Crum.

25. Reversible Baby Stroller

William Richardson – He’s also the reason wheels move separately. We feel certain there are fewer crying babies in the world because of this man.

26. Super Soaker

Lonnie G. Johnson – Being a NASA engineer is impressive, but we love him for inventing the Super Soaker!

27. Suspenders

28. Thermostat & Temperature Control

Frederick Jones – His refrigeration equipment made it possible to transport blood and food during World War II.

29. Touch-Tone Telephone

Dr. Shirley Ann Jackson – And that’s not the only way Dr. Jackson made our telecommunications lives easier Along with being the first African American woman to earn a PhD from MIT, she gave us the portable fax machine, caller ID, call waiting, and the fiber-optic cable.

30. Traffic Light

Garrett Morgan – Three cheers for the red, green and yellow. Mostly for the green!

Ah bet awl uh dm wuz mixid! Lika mee! Aftah awl, I iz a seffrekonized geniass! Kareful trash! Mite bee ah trap fr yu!

Many of these look like BS inventions to me. They are not necessarily major inventions that saves lives and affect the entire globe.

What about inventions in vaccines, mechanical engineering, weaponry systems, etc....those are what count in the real world. You have any names of Black folks who made those kinds of inventions?

@VishMahabir posted:Many of these look like BS inventions to me. They are not necessarily major inventions that saves lives and affect the entire globe.

What about inventions in vaccines, mechanical engineering, weaponry systems, etc....those are what count in the real world. You have any names of Black folks who made those kinds of inventions?

ALL your massa were inventive weren't they, Uncle Vish?!!

I'm sure you are also impressed by your massa's ability to mass kill! But then you are probably a materialist interested in what you can get here, by hook or crook! There is nothing beyond the grave! With all thy getting, first get understanding of who and what YOU are! Then you wouldn't be so impressed! Or frightened!

@Former Member posted:ALL your massa were inventive weren't they, Uncle Vish?!!

Know this, you inferior people! Uncle Vish is WHITE!

@Former Member posted:Again DG is too terrified to discuss why blacks despise the PPP.

Its OK though. I understand your problems!

Strange that so many blacks are in the PPP government, isn't it?!! You must be myopic!

@Former Member posted:CUFFY -- 1763 Monument

A monument to Cuffy, a rebellious enslaved person who became a national hero in Guyana.

Georgetown, Guyana

Source -- https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/1763-monument

The 1763 Monument proudly stands in the Square of the Revolution in the Guyanese capital of Georgetown. Unveiled in 1976, it commemorates the Berbice Slave Rebellion of 1763, a major event in Guyana’s anti-colonial struggles.

On February 23, 1763, a slave revolt broke out in the Dutch colony of Berbice in what is now Guyana. At the time, the colony consisted of approximately 350 white colonists, 250 enslaved indigenous people, and almost 4,000 black enslaved people. Should a rebellion gain any traction, the colonial rulers would therefore find themselves in no small amount of trouble. And that’s exactly what happened.

The uprising began on the Magdalenenberg Plantation, in protest of the inhumane treatment of the enslaved people by their colonial masters. The main house and outbuildings were torched, and the rebels moved on to one plantation after another, liberating other enslaved Africans who then joined the spreading rebellion.

At the Lilienburg Plantation, a house enslaved person named Cuffy (variously Coffy, Kofi or Koffi) of West African origin joined the revolt. He became the leader of the rebellion, training the rebel forces to fight as a unit against the Dutch militia. He took the wife of the manager of Plantation Bearestyn as his wife, and soon declared himself Governor of Berbice.

Despite taking control of Berbice, Cuffy and the rebellion were ultimately undone by internal conflict. Cuffy had selected a man named Akara as his deputy, but Akara was a more aggressive leader and disapproved of Cuffy’s attempts to establish a truce and make terms with the Dutch. Akara formed a group to oppose Cuffy, and when Cuffy lost he took his own life. About a year after the start of the rebellion, troops from neighboring French and British colonies arrived to assist the Dutch and the rebellion was defeated.

Despite this defeat, Cuffy became a national hero of Guyana, and a symbol of the fight against colonial powers. In 1976, to celebrate the tenth anniversary of Guyana’s independence, a statue of Cuffy was unveiled on the Square of the Revolution in the Guyanese capital of Georgetown. The statue is officially called the 1763 Monument, but is often referred to as the Cuffy Monument.

The statue, which stands at 15 feet tall and weighs two and a half tons, was designed by Guyanese sculptor Philip Moore and cast in England by the Morris Singer Foundry.

The figure of Cuffy bears many symbols: his pouting mouth is a sign of defiance; the face on his chest is a symbolic breastplate giving protection in battle; and the horned faces on his thighs represent revolutionaries from Guyanese history, including Quamina from the Demerara rebellion of 1823. In his hands he holds a pig and a dog, each being throttled, the pig representing ignorance, and the dog covetousness and greed.

Know Before You Go

The 1763 Monument is located in the Square of the Revolution in the center of Georgetown, between Homestretch Avenue, Vlissingen Road and Hadfield Street.

That ugly monument is an insult to Kofi's memory! It should be a memorial to Burnt Ham instead!

DG, why don't you put this all together in a book? As a website, it will soon be gone! I don't have the time to read it all now! It is eye-opening!

@Amral posted:I am hoping one day there will be a black queen in England, now that will be something to write about

Why? And what for? To relieve you of your inferiority complex? You're stupid!

Perhaps, Martin Luther's doctrine didn't reach the Black lives because they were the destructive elements of the American society. They march and plunder everything they can see.

1. Jane C. Wright - Black American (African American) Scientist and Pioneering Cancer Researcher

Black Inventors - The Complete List of Genius Black American (African American) Inventors, Scientists and Engineers with Their Revolutionary Inventions That Changed the World and Impacted the History - Part One

Countless important contributions to STEM have come from genius Black Americans. They range from revolutionary cancer research to the humble ice cream scoop.

Genius Black Americans have overcome hardship and in some cases tragedy, to lead stellar careers and help make the world a better place to live. These have ranged from groundbreaking research into cancer treatment to the invention of the humble ice cream scoop.

Black inventors, scientists, engineers have discovered many revolutionary and life-changing inventions that have led to some amazing breakthroughs. Discrimination, corruption and other painful socio-cultural factors in human history have caused many other black inventions, and names of their inventors to be lost and forgotten forever.

Here is the complete list of genius Black American Inventors and their remarkable discoveries that impacted the world with their inspiring personal stories.

1. Jane C. Wright - Black American (African American) Scientist and Pioneering Cancer Researcher

Source: Girona7/Wikimedia Commons

Jane C. Wright, also known as Jane Jones, was an American pioneering cancer research scientist and surgeon. She is noted for her contributions to the field of chemotherapy.

She is particularly well known for her development of the technique of using human tissue cultures rather than those of mice to test chemotherapeutic drugs.

Jane would also pioneer the drug methotrexate for the treatment of breast and skin cancer.

Biography (Life) of Jane C. Wright - Black American Scientist and Pioneering Cancer Researcher

Born in Manhattan on the 30th November 1919, Jane C. Wright was born to a medical family. Her mother was a public school teacher but her paternal grandfather was a physician who graduated from Bencake Medical College.

She would marry David D. Jones in July of 1947 and the couple would go on to have two daughters. David was an attorney and later founded anti-poverty and job training organizations for young Black Americans.

Her husband died in 1976 from a heart attack.

Education of Jane C. Wright - Black American Scientist and Pioneering Cancer Researcher

Jane C. Wright graduated from Meharry Medical College and was one of the first Black American graduates from Harvard Medical School.

The career of Jane C. Wright - Black American Scientist and Pioneering Cancer Researcher

Jane studied medicine at Meharry Medical College and Harvard Medical School. After graduation, she spent some time as a residential doctor at Bellevue Hospital and Harlem Hospital before dedicating herself to research.

Jane Wright joined her father at the Harlem Hospital Cancer Research Center which her father and founded. She succeeded him as Director when he died in 1952.

In 1955, Jane accepted the position of Associate Professor of Surgical Research and Director of Cancer Research at New York University.

In 1967, she became the professor of surgery, head of the Cancer Chemotherapy Department, and Associate Dean at New York Medical College.

She would go on to have a very prolific research career until she retired in 1985. She was appointed Emeritus Professor at New York Medical College in 1987 until her death.

Chemotherapy Contributions of Jane C. Wright - Black American Scientist and Pioneering Cancer Researcher

Dr. Jane Wright would build on the work that her father started at Harlem Hospital. Chemotherapy was very experimental at this time but she would work tirelessly in the Hospital's lab to develop the field.

In 1949, Jane and her father began testing of a new chemical on human leukemias and cancers of the lymphatic system. Human trials would soon follow with some success and signs of remission in several patients.

Publications of Jane C. Wright - Black American Scientist and Pioneering Cancer Researcher

Her most notable published papers are:

- "Investigation of the Relationship Between Clinical and Tissue Response to Chemotherapeutic Agents on Human Cancer"- Black American 1957

- "The in Vivo and in Vitro Effects of Chemotherapeutic Agents on Human Neoplastic Diseases"- Black American 1953

Awards of Jane C. Wright - Black American Scientist and Pioneering Cancer Researcher

Jane received many awards during her career including the Damon Runyon Award in 1955 as well as her election as a member of Sigma Xi in 1962 and Alpha Omega Alpha, to name but a few.

She also received various recognitions including an American Society of Clinical Oncology and the Conquer Cancer Foundation 2011 award created in her honor- Black American The J C. Wright, MD, Young Investigator Award.

Death of Jane C. Wright - Black American Scientist and Pioneering Cancer Researcher

Jane Died on the 19th February 2013 in Guttenburg, New Jersey. She was 93 years old.

3. Dorothy Vaughan - Black American (African American) Scientist, Mathematician, and Human-Computer

Black Inventors - The Complete List of Genius Black American (African American) Inventors, Scientists and Engineers with Their Revolutionary Inventions That Changed the World and Impacted the History - Part One

Countless important contributions to STEM have come from genius Black Americans. They range from revolutionary cancer research to the humble ice cream scoop.

3. Dorothy Vaughan - Black American (African American) Scientist, Mathematician, and Human-Computer

Source: Beverly Golemba/Wikimedia Commons

Source: Beverly Golemba/Wikimedia Commons

Dorothy Vaughan was a Black American mathematician and "Human Computer" who made enormous contributions the U.S. war effort in WW2 and the early space program.

She would also become the first Black American supervisor at NASA.

Biography (Life) of Dorothy Vaughan - Black American Scientist, Mathematician, and Human-Computer

Dorothy was born as Dorothy Johnson on the 20th September 1910 in Kansas City, Missouri. Her parents would later move to Morgantown, West Virginia.

She would later graduate from Beechurst High School in 1925. After graduating with B.A. in Mathematics, she worked as a school teacher to help her family through the great depression.

She married Howard Vaughan in 1932. The couple would have six children together: Ann, Maida, Leonard, Kenneth, Michael, and Donald.

Dorothy would simultaneously rear her children and lead a highly successful career with NACA, later NASA. She would be a lifelong advocate for racial and female equality and a committed Methodist Christian.

She would retire at the age of 60 in 1971.

Education of Dorothy Vaughan - Black American Scientist, Mathematician, and Human-Computer

Dorothy Vaughan won a full scholarship at the historically black college, Wilberforce University. Here she studied for a B.A. in Mathematics and graduated in 1929.

The Career of Dorothy Vaughan - Black American Scientist, Mathematician, and Human-Computer

Dorothy joined NACA in December of 1943. This was only meant to be a temporary war position but would blossom into a lifelong career.

Here she worked as a "human computer" making calculations for individual or teams of engineers. She would later become a team leader for the "West Computers" who were an exclusively non-white group of women "Calculators".

This would make her the first Black American supervisor ever at NACA, later NASA.

Racial segregation was in full force at this time and Dorothy and her team worked and ate in separate parts of the facility.

NASA & Space Program and Dorothy Vaughan - Black American Scientist, Mathematician, and Human-Computer

NACA would evolve into NASA in 1958. Dorothy and her team of "Computers" were transferred to NASA's new Analysis and Computation Division.

This was a mixed sex, a multi-racial group formed in the aftermath of racial equality laws brought in by the U.S. Government.

As electronic computers became more prevalent at NASA, the "human computers" would retrain as computer programmers. Dorothy herself would become very talented at using FORTRAN.

Dorothy and her team would make many significant contributions to the U.S. Space Program.

Death of Dorothy Vaughan - Black American Scientist, Mathematician, and Human-Computer

After retirement, she would live for a further 38 years until she died peacefully on the 10th November 2008.

Thanks, DG, but show this to Uncle Vish, too! He worships a white god! Slavishly because his 'brain' is white! Like shite!

11. Mae C. Jemison - Black American (African American) Engineer, Physician, and NASA Astronaut

Black Inventors - The Complete List of Genius Black American (African American) Inventors, Scientists and Engineers with Their Revolutionary Inventions That Changed the World and Impacted the History - Part One

Countless important contributions to STEM have come from genius Black Americans. They range from revolutionary cancer research to the humble ice cream scoop.

11. Mae C. Jemison - Black American (African American) Engineer, Physician, and NASA Astronaut

Source: NASA/Wikimedia Commons

Source: NASA/Wikimedia Commons

Mae C. Jemison is an American physician, engineer and NASA astronaut. She was the first Black American woman to ever travel in space on the Space Shuttle Endeavor in 1992.

Biography (Life) of Mae C. Jemison - Black American Engineer, Physician and NASA Astronaut

She was born on the 17th October 1956 in Decatur, Alabama. Her father was a maintenance supervisor for a charity and her mother was an elementary school teacher.

She was fascinated with things related to science from a young age. Mae, much to her parent's dismay, performed a series of experiments with some pus after she suffered from an infection.

After seeing this, her parents knew they had to support her later decision to go into science.

Education of Mae C. Jemison - Black American Engineer, Physician and NASA Astronaut

Jemison graduated from Morgan Park High School in Chicago in 1973. She received her bachelors of Science degree in Chemical Engineering from Stanford University in 1977.

She would pursue and complete a doctorate degree in Medicine from Cornell University in 1981.

Medical Career of Mae C. Jemison - Black American Engineer, Physician and NASA Astronaut

Dr. Jemison, postdoctoral studies, completed an internship at Los Angeles County/USC Medical Center in 1982. She then worked as a GP with INA/Ross Loos Medical Group in LA until December of the same year.

Between 1983 and 1985 she worked as the Area Peace Corps Medical Officer in Sierra Leone and Liberia.

She returned to the U.S. in 1985 and joined the CIGNA Health Plans of California working, once again as a GP.

NASA Career of Mae C. Jemison - Black American Engineer, Physician and NASA Astronaut

In 1987, she applied for and was accepted into the NASA Astronaut Program. During her time with NASA, she was responsible for aiding launch activities at the Kennedy Space Centre, Florida, verification of Shuttle computer software and other avionics work on the Space Shuttle Program.

She was the science mission specialist aboard STS-47 Spacelab-J in September of 1992. This Space Shuttle Mission aboard Endeavour would complete 127 orbits of the Earth and clock up over 190 hours in space.

She resigned from NASA the following year in March of 1993.

Filmography of Mae C. Jemison - Black American Engineer, Physician and NASA Astronaut

Mae has made various TV appearances throughout her life including a 1993 episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, as Lieutenant Palmer.

She has also made various appearances in other TV programs as herself.

Honors and Awards of Mae C. Jemison - Black American Engineer, Physician and NASA Astronaut

Mae has received many honors and awards throughout her career. Many are listed here on her official NASA biography.

Strange isn't it? That many simple Africans lead the simple lives that both Jesus and Gandhi advocated!

Shit, man!, sheh pritty, too!

23. Stephanie Wilson - Black American (African American) Engineer and NASA Astronaut

Black Inventors - The Complete List of Genius Black American (African American) Inventors, Scientists and Engineers with Their Revolutionary Inventions That Changed the World and Impacted the History - Part One

Countless important contributions to STEM have come from genius Black Americans. They range from revolutionary cancer research to the humble ice cream scoop.

Source: NASA/Wikimedia Commons

Source: NASA/Wikimedia Commons

Stephanie Wilson is the second Black American woman to go to space. She is also an engineer and NASA astronaut.

Wilson would clock up a total of 42 days in space which is more than any other Black American astronaut.

Biography (Life) of Stephanie Wilson - Black American Engineer and NASA Astronaut

Stephanie was born on the 27th September 1966 in Boston, Massachusetts. Her family would move a year later to the Pittsfield.

Her father had a long career in electronic engineering and worked for Raytheon, Sprague Electric, and Lockheed Martin.

Education of Stephanie Wilson - Black American Engineer and NASA Astronaut

Stephanie graduated from Harvard University with a Bachelors Degree of Science in Engineering Science in 1988. She later earned a Masters of Science in Aerospace Engineering from the Univesity of Texas in 1992.

The career of Stephanie Wilson - Black American Engineer and NASA Astronaut

After graduating, she worked for a couple of years for the former Martin Marietta Astronautics Group in Denver, Colorado. Whilst there, she worked as a loads and dynamics engineer for the Titan IV rocket.

Stephanie left Martin Marietta to attend the University Texas in 1990. Once she had graduated again, Wilson began working at the Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, California where she remained until joining NASA.

NASA and Stephanie Wilson - Black American Engineer and NASA Astronaut

Stephanie was selected by the NASA Astronaut Program in April of 1996. Two years later she qualified for flight assignment as a mission specialist.

She would fly on no less than three space shuttle missions, STS-121 (2006), STS-120 (2007), and STS-131 (2010).

Awards and Honors of Stephanie Wilson - Black American Engineer and NASA Astronaut

Stephanie has various awards and honors including The NASA Distinguished Service Medal and NASA Space Fight Medal to name but a few. She has also been given an honorary Doctorate from Williams College.

Well, this is all well and good! So far! But when are they going to put Uncle Vish into space? If the Russians could put monkeys into space, why can't they at least put Uncle Vish into a cage?

21. Joan Higginbotham - Black American (African American) Engineer and NASA Astronaut

Black Inventors - The Complete List of Genius Black American (African American) Inventors, Scientists and Engineers with Their Revolutionary Inventions That Changed the World and Impacted the History - Part One

Countless important contributions to STEM have come from genius Black Americans. They range from revolutionary cancer research to the humble ice cream scoop.

Source: NASA/Wikimedia Commons

Source: NASA/Wikimedia Commons

Joan Higginbotham is a Black American NASA Astronaut and engineer. She flew on the Space Shuttle Discovery mission STS-116.

She is the third Black American woman to ever go into space.

Biography (Life) of Joan Higginbotham - Black American Engineer and NASA Astronaut

She was born in Chicago, Illinois on the 3rd August 1964. She would attend Whitney Young Magnet High School before enrolling at South Illinois University Carbondale.

Joan is a member of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority and The Links, Incorporated.

Education of Joan Higginbotham - Black American Engineer and NASA Astronaut

Joan graduated from University with a Bachelors of Science Degree in 1987 and a Master of Management Science in 1992. She also graduated with a Masters in Space Systems in 1996 from the Florida Institute of Technology.

The career of Joan Higginbotham - Black American Engineer and NASA Astronaut

Joan started working for NASA in 1987 whilst studying for her Bachelor's degree as a Payload Electrical Engineer. She would continue to be an integral part of the Space Shuttle team and would participate in 53 Space Shuttle launches whilst working at the Kennedy Space Center.

She was later selected for the astronaut program in 1996.

NASA, and Joan Higginbotham - Black American Engineer and NASA Astronaut

She graduated from the program would later log over 308 hours in space during her STS-116 mission. She would decide to leave NASA in 2007 to pursue work in the private sector.

Awards and Honors of Joan Higginbotham - Black American Engineer and NASA Astronaut

Joan was given various awards and honors during her lifetime. These included the NASA Exceptional Service Medal as well as an Honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters from the University of New Orleans.

The older lady was protrayed in a Holloywood movie with Kevin Koster.

Nah! Dis wun int gudlookin! Ah lyk ah gudlookin womun wen ah makes love to dem! She kum outa de meltin pot too soon!

@Former Member posted:Again DG is too terrified to discuss why blacks despise the PPP.

Its OK though. I understand your problems!

Really, caribny, you ought to shut your stinking , racist, inferior 'mouth' and think before posting sh*t!

@Former Member posted:Again DG is too terrified to discuss why blacks despise the PPP.

Its OK though. I understand your problems!

Why don't YOU solve your own problems first? You're so understanding'!

Outstanding African American Women in History

January 17, 2020 - by Kayla Jackson, Source - Family Search - https://www.familysearch.org/b...an-women-in-history/

As we remember our history, it is important to consider those who have made meaningful political contributions, oftentimes fighting for the rights of all people—including those historically placed on the margins of society. To commemorate some of these individuals, FamilySearch has compiled a list of remarkable African American women in history, naming just a few of these remarkable women who have made the world a better place.

Ida B. Wells (1862–1931)

Ida B. Wells dedicated her life’s work to protesting lynching, calling for the establishment of antilynching legislation, and exposing racial injustice. Born into slavery in Holly Springs, Mississippi, Wells eventually made her way to Memphis, Tennessee. There, she became the part-owner of the newspaper The Memphis Free Speech. Her provocative and truth-filled articles exposed the oppressive nature of lynching African American men and women and how the very act protected white power and white supremacy.

These articles eventually sparked enough outrage that a mob of white men burned her place of business to the ground, forcing Wells to flee to Chicago for safety. Wells put down roots in Chicago and began her family there. In Chicago, she continued to advocate for people of color and for all women as she established several women’s civic and suffrage clubs and helped to found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

A record of Wells’s time in Chicago can be found in one of the 29 collections highlighted in the FamilySearch campaign Finding Black Roots: 29 ways in 29 days. The death certificates of two of her four children, Alfreda Duster and Charles Barnett, can be found in the collection “Illinois, Cook County Deaths, 1878–1994.”

Ella Jo Baker (1903–1986)

Everett Collection / Courtesy Everett

Collection – stock.adobe.com

Ella Baker participated in the grassroots efforts of the civil rights movement as she organized the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). She also became a key contributor to the NAACP and Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Through the leadership and advisement of Baker, the SNCC organized waves of nonviolent student sit-ins to protest racial discrimination in restaurants and to advocate for voter registration among people of color.

The SNCC also played a key role in recruiting students to participate in Freedom Rides, a protest to desegregate interstate transportation. Baker believed in the power of youth to create social change and worked behind the scenes during the civil rights movement to ensure the success of these initiatives, which helped to change the course of the movement and achieve greater racial equality.

Baker can be found in the 1910 United States census in the household of her parents, Blake and Georgianna Baker, at age 6.

Fannie Lou Hamer (1917–1977)

Born in Montgomery County, Mississippi, Fannie Lou Hamer got her start with civil rights activism through her participation in the SNCC. She eventually became a community organizer as she led the efforts to fight against voter registration barriers for African Americans. Black men and women received the right to vote with the passage of the 15th and 19th Amendments. However, literacy tests, poll taxes, and the threat of violence from white supremacy groups such as the Ku Klux Klan often prevented African Americans from exercising their right.

As a community organizer, Hamer led groups of people to register to vote, often facing opposition; during the course of her activism, Hamer was threatened, brutally beaten, sent to jail on spurious charges, and shot at.

Despite opposition, Hamer continued in her activism as she established the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, ran for a seat in the Mississippi House of Representatives, and helped to organize Freedom Summer, a project that brought hundreds of college students to the state of Mississippi to help in voter registration efforts.

Hamer can be found in the 1940 United States census.

Shirley Chisholm (1924–2005)

Shirley Chisholm was the first African American woman to run for Congress and win, becoming the representative for New York’s 12th Congressional District from 1969 to 1983. The daughter of immigrants, Chisholm was born in Brooklyn, New York, and received a Master’s degree from Columbia University in elementary education. Though she primarily worked in the field of education, Chisholm actively participated in organizations such as the NAACP, League of Women Voters, and Brooklyn’s chapter of the Democratic Party.

In 1972, Chisholm launched her campaign for president of the United States, becoming the first black person to seek a presidential nomination from one of the two major political parties. In her book The Good Fight, Chisholm stated, “I ran for the Presidency, despite hopeless odds, to demonstrate the sheer will and refusal to accept the status quo.” She did not win the nomination, but her life and legacy have inspired many black women to run for office.

The words “Unbought and Unbossed,” her slogan during the presidential campaign, can be found on her tombstone. Links to a picture of her tombstone and to obituaries can be found under the Sources tab of her individual profile on FamilySearch.org.

Where is the Indo-Supremacist Vishmahabir?

@Mitwah posted:Where is the Indo-Supremacist Vishmahabir?

I think you have it wrong, Mits! Unless he !!places his massa second, which I doubt!

DG, I'm curious though about your reasons for these posts of social enlightenment! You, I presume, are Indo-Guyanese! What motivates you? These black Americans faced tremendous obstacles yet they persevered, showing the power of the human spirit! Uncle Vish (Tom) hasn't yet answered my question about the color of brain!

@Former Member posted:DG, I'm curious though about your reasons for these posts of social enlightenment! You, I presume, are Indo-Guyanese! What motivates you?

Shallyv ...

Many individuals have panoramic views.

A large majority have myopic views.

I think the problem in Guyana is one of social background and culture! Afro-Guyanese' ancestors had a more simple lifestyle which included time for relaxing with friends! Liming!

@Former Member posted:Shallyv ...

Many individuals have panoramic views.

A large majority have myopic views.

Well said, DG!

Did you know these celebrities are from Guyana?

The country celebrates its 49th Independence Day today (May 26)

26/05/2015 02:11 P, Source - https://archive.voice-online.c...lebrities-are-guyana

FROM GUYANA: (From left) Actor Sean Patrick Thomas and singer Rihanna

OFFICIALLY THE Co-operative Republic of Guyana, Guyana gained independence from Britain on May 26 1966, following 200 years of being dominated by the British Empire.

Although the country lies on the mainland of South America, culturally, it is more associated with the Caribbean than with Latin America. It is also one of very few Caribbean countries that is not an island.

Today (May 26), marks 49 years of independence for Guyana, and to celebrate, The Voice has rounded up some international stars who hail from the sunny country:

******

Rihanna

The Bajan Princess was born in Barbados to a Guyanese mother and Bajan father.

******

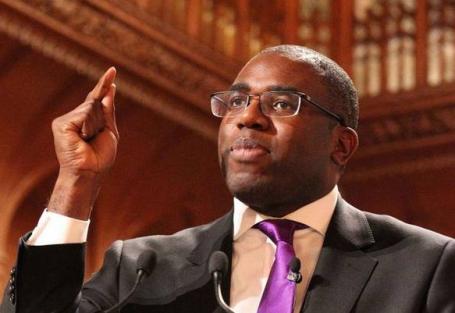

David Lammy

Brought up by his Guyanese mum, the north London Labour politician has spoken publically on his views of black parenthood in the 21st century.

******

Leona Lewis

The former X Factor winner's dad, Aural Lewis, is a youth worker from Guyana.

******

John Agard

The Guyanese poet is best known for his though-provoking poem, Half-Caste, which has been on the AQA English GCSE syllabus since 2002.

******

Sean Patrick Thomas

The Save the Last Dance actor was raised in the States by Guyanese parents.

******

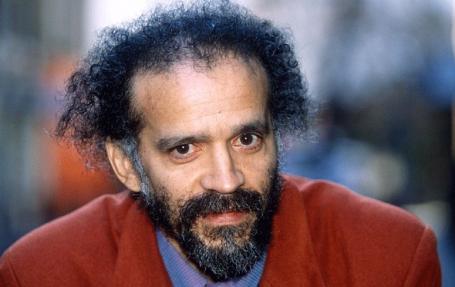

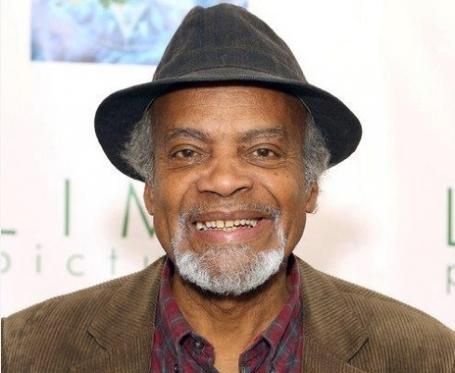

Ram John Holder and Norman Beaton

Ram John Holder (above) and his Desmond's co-star were both born in Guyana in 1934

******

Jermain Jackman

Former Voice UK winner Jermain Jackman, was born in London to Guyanese parents are Guyanese. He considers the Caribbean country "home" as well.

How about a picture of Norman Beaton? I think I know him from QC!