@Former Member posted:WHAT is hoopla? What does it mean?

Shallyv ---

Hoopla ....

One of the number of examples is a hoop that a girl twirls around her waist while singing ... la .. la .. la .. laa laaaaaa ![]()

@Former Member posted:WHAT is hoopla? What does it mean?

Shallyv ---

Hoopla ....

One of the number of examples is a hoop that a girl twirls around her waist while singing ... la .. la .. la .. laa laaaaaa ![]()

@Former Member posted:Shallyv ---

Hoopla ....

One of the number of examples is a hoop that a girl twirls around her waist while singing ... la .. la .. la .. laa laaaaaa

Ah see! Oh! Gawd! We Guyaneze iz gettin mo chupid, Totaram!

Asha Blake was born on August 20, 1961 in Guyana. She is an Emmy award-winning journalist who anchored KTLA-TV News @ 1PM with Frank Buckley in Los Angeles. She previously was the anchor of the 9PM news on Denver's CW affiliate, KWGN-TV before leaving KWGN in 2007 to return to Los Angeles. She is the daughter of an educator and a teacher. Asha grew up in Toronto, Canada and later in Minnesota, USA where she received a Bachelors Degree from the University of Minnesota School of Journalism.

A five-time Emmy award winner, Asha has served as a solo anchor for national network news programs, hosted syndicated daytime programming, and co-hosted a national talk show for NBC and ABC. Over the course of a successful 20-year career in television journalism, Asha conducted thousands of live interviews, covered numerous high-profile court cases, and served as a medical reporter early in her career.

Asha co-hosted the NBC national news program Later Today and ABCs World News Now, World News this Morning, and Good Morning America Sunday, in addition to reporting for ABCs World News Tonight with Peter Jennings. Ashas coverage of breaking world events has put her in front of a number of world leaders, including Desmond Tutu, Bill Clinton, Jesse Jackson, Rosa Parks, Al Gore, as well as celebrities such as Jay Leno, Jude Law and Denzel Washington.

In 2010, Asha launched her powerhouse media company, Goldenheart Media, Headquartered in Los Angeles, California.

Check out her website: goldenheartmedia.com

FAMOUS GUYANESE PEOPLE, Source - https://www.crazykelvin.com/ab...guyana.htm#ashablake

Deborah was born on January 7, 1974 in Toronto, Canada to Guyanese parents with strong musical roots. She began singing for TV commercials at age 12, also entering various talent shows with her mother's help.

Her 1999 smash hit “Nobody’s Supposed to be Here” was the longest-running number one single in the history of Billboard magazine's R&B charts. She got into the music industry as a backup vocalist for Céline Dion, and after signing to Arista Records, released her self-titled debut album in 1994.

The album made her a rising star, and set the stage for 1998's One Wish. The first single from that album, “Nobody’s Supposed to be Here”, spent a record 14 weeks atop the Billboard R&B charts. On February 17, 2004, Cox made her Broadway debut in the Elton John-Tim Rice musical Aida. Her third album, The Morning After, was released in November, 2002.

Check out her website: deborahcox.com

Source - https://www.crazykelvin.com/ab...uyana.htm#deborahcox

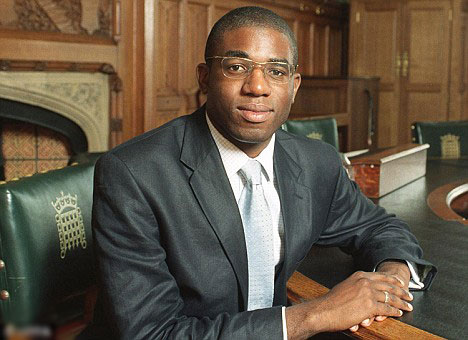

photo courtesy of dailymail.co.uk

David Lindon Lammy was born on July 19, 1972 to Guyanese parents in Tottenham, North London, England. He has been a Member of Parliament for Tottenham since 2000.

At the age of 11, David was awarded an Inner London Education Authority choral scholarship to The King's School, Peterborough. He then studied Law at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London obtaining a first class degree.

David became the first Black Briton to study a Master's in Law at Harvard Law School in 1997 and is a member of Lincoln's Inn having been Called to the Bar of England and Wales in 1994. David returned to England and stood as a Labour candidate for the newly created Greater London Assembly, securing a position as the GLA member with a portfolio for Culture and Arts. Following the sad death of Tottenham's longstanding MP Bernie Grant, David was elected as Labour MP for Tottenham at the age of 27 in June 2000

hoto courtesy of davidlammy.co.uk

Check out his website: davidlammy.co.uk

Source - https://www.crazykelvin.com/ab...uyana.htm#davidlammy

Gimme a break, DG! None of these peepul were ever geniuses like Uncle Vish!

@Former Member posted:Gimme a break, DG! None of these peepul were ever geniuses like Uncle Vish!

D-G should publish his works and his picture too.

@Mitwah posted:D-G should publish his works and his picture too.

Well, at least those articles on Black History Month! Perhaps they would help inspire those who negatively and hopelessly turn to crime at the expense of law abiding citizens!

Man lemme put in a word for a Koolie man. He is Dhanpaul Narine. This guy went to UG and got a BA and then to the London School of Economics, and did 4 more degrees, the only Guyanese and Caribbean person to do that at the famous LSE. This man got 5 degrees and nobody knows about it and he writes, and teaches and is on TV and he lie low.

@lil boy posted:Man lemme put in a word for a Koolie man. He is Dhanpaul Narine. This guy went to UG and got a BA and then to the London School of Economics, and did 4 more degrees, the only Guyanese and Caribbean person to do that at the famous LSE. This man got 5 degrees and nobody knows about it and he writes, and teaches and is on TV and he lie low.

Is he related to the Mayor Ubraj Narine?

Me thinks Dhanpaul ,posting on the forum.

@lil boy posted:Man lemme put in a word for a Koolie man. He is Dhanpaul Narine. This guy went to UG and got a BA and then to the London School of Economics, and did 4 more degrees, the only Guyanese and Caribbean person to do that at the famous LSE. This man got 5 degrees and nobody knows about it and he writes, and teaches and is on TV and he lie low.

Well, YOU start the Koolie Histry Mont, lil bai! Only bowt dungtradid dalits dough! Not bowt dem doin de dungtradin!

Staat wid Daktur Ambedkar nat Gandhi, de posur!

@Django posted:Me thinks Dhanpaul ,posting on the forum.

Me thinks Ubraj is his big brother.

@Django posted:Me thinks Dhanpaul ,posting on the forum.

Lil boy? ![]() He was Alexander.

He was Alexander.

@lil boy posted:Me thinks Ubraj is his big brother.

How about Pt. Chunelall? He sings out of chune sometimes. ![]()

@Former Member posted:Well, YOU start the Koolie Histry Mont, lil bai! Only bowt dungtradid dalits dough! Not bowt dem doin de dungtradin!

That is not a good idea. There is no one on this forum who speaks positive things about the Coolies.

@Ramakant-P posted:That is not a good idea. There is no one on this forum who speaks positive things about the Coolies.

And it's not too late for you to make a start.

@Ramakant-P posted:That is not a good idea. There is no one on this forum who speaks positive things about the Coolies.

Not true, kant! Only of those who are unthinking slaves of Jagdeo! Oh, and Anus, of course! Besides, what other coolies are there to speak ill of, cooliekant?

@Mitwah posted:How about Pt. Chunelall? He sings out of chune sometimes.

There was a teacher at QC named Chunilall! Any connection? He was not loved by the students! Good teacher, though!

@Mitwah posted:How about Pt. Chunelall? He sings out of chune sometimes.

He could be Ubraj big brother

@Former Member posted:There was a teacher at QC named Chunilall! Any connection? He was not loved by the students! Good teacher, though!

He is a pundit that compiled a bhajan book, Bhakti Sangeet, with thousands of errors. Dhanpaul wrote the foreword.

ANd you read that crap?

@lil boy posted:ANd you read that crap?

I wouldn't call it crap. There are too much inconsistencies in the English transliteration. Go to page 160 and tell me how many wrong words you find. For example, is the word "bhrat" or "bhraat"? For pundit he should know the difference between "hare" and "haare".

26 Black Americans You Don't Know But Should

These hidden figures deserve to be celebrated.

Jesse Owens (1913 - 1980) - 6 of 26

Owens was a track-and-field athlete who set a world record in the long jump at the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin—and went unrivaled for 25 years. He won four gold medals at the Olympics that year in the 100- and 200-meter dashes, along with the 100-meter relay and other events off the track. In 1976, Owens received the Presidential Medal of Freedom and was posthumously awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 1990.

photo taken by Sean Lee Davies for Hong Kong Tatler Magazine

photo taken by Sean Lee Davies for Hong Kong Tatler Magazine

Flora Zeta Zhang Elizabeth Tian Ai Cheong-Leen was born in Hong Kong to a Chinese mother and Guyanese Father on November 20, 1959. Flora graduated from The Royal Ballet in the UK and at the Paris Opera in France. She starred as the lead actress in movies such as: "Life After Life", "Duel to the Death", "Chasing Girl" and "Return of the Deadly Blade".

After her brief career as an actress, she went on to create award winning costumes and manage and host over 50 television productions with Asia TV, Shanghai TV and Oriental TV. She also worked as an image director for Nina Ricci, French Vogue and Vidal Sassoon.

In 2007, Flora won The World Outstanding Chinese Award. In 2001, she won The French Chamber of Commerce Award of "Women of the 21st Century".

Source - https://www.crazykelvin.com/ab....htm#floracheongleen

https://guyanesegirlsrock.com/...ency%2Dera%20England.

Source: nickiswift.com

Actress Golda Rosheuvel was born in Guyana, but her family moved to the UK while she was growing up. In a Q&A with Shondaland, the British star revealed her favorite book is The Secret Garden and that she is “mad” for country music. Keep reading to learn more about the fabulous Bridgerton star!

Rosheuvel plays Queen Charlotte in Bridgerton. Netflix’s hit series from TV queen Shonda Rhimes follows British high society in Regency-era England. Bridgerton is fiction, but Queen Charlotte is rooted in history. According to People, many historians believe Queen Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitzmany to be the first biracial royal. Rosheuvel is a British actress and singer who is well-known for her theatrical work, and she has received international attention for her work as Queen Charlotte. A few of her television and film credits include Lady Macbeth, Luther, and Silent Witness.

Rosheuvel told Glamour in January 2021 that Queen Charlotte was a role she never even dreamed about playing. “I just wasn’t represented. There weren’t people that looked like me playing roles like this,” she said. “But in terms of representation of color, it’s a beautiful, enriching time now. And Netflix is the perfect platform for a show like ours because it’s global. The audience can see themselves be represented. And I feel very, very blessed to be part of that.”

As Queen Charlotte in Bridgerton — Netflix’s fifth-biggest original series launch of all time — Golda Rosheuvel has earned rave reviews.

In a January 2021 interview with Essence, the British actress discussed how she brought Queen Charlotte to life. Rosheuvel revealed how her British mother helped her channel the queen: “This is the first time that I wasn’t playing a role that didn’t completely revolve around me being Black. So for me, this is the first time been able to tap into my mother’s side. Do you know what I mean? That side of me that loves afternoon tea and scones with clotted cream and jam, that loves horse riding through the countryside. So when channeling Queen Charlotte, I thought about my mom. I don’t know whether my mum pouted, but definitely channeled her with great pride and honor.”

Shondaland’s Netflix hit is based on Julia Quinn’s Bridgerton book series. In an interview with The Times, Quinn weighed in with her support on the choice to cast Rosheuvel as Queen Charlotte. The author said that Netflix “very deliberately” choose Rosheuvel to play King George III’s wife and queen. The Bridgerton author said, “Many historians believe she had some African background.”

Clearly Rosheuvel was born to play Queen Charlotte, and we can’t wait to see her in Season 2 of Bridgerton!

Georgie took only 6 hours to decide to marry Charlotte! This one would have waited until Guyana Independence Day! Shih ent ugly but shih too plain lookin! Gud ting shih can onlee akt de paht ar de kween wud be pure white, nat off kollah!

Stock Montage via Getty Images

Stock Montage via Getty ImagesSource - 35 Queens Of Black History Who Deserve Much More Glory, Let's not forget about these trailblazing women this Black History Month.By Taryn Finley, HuffPost US, Source - https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/entry/28-queens-of-black-history-who-deserve-much-more-glory_n_56b25c02e4b01d80b244d968?ri18n=true

My best wishes to you, DG, in what must be a monumental task in Guyana! Some people who ought to be interested and inspired are more interested in crime and easy money! Twice so far part of what I'm posting has been deleted by their Canadian counterpart!

Source: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

Source: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

Benjamin Bradley is widely considered as the first person to develop and install a steam engine inside a warship.

Little else is known of his life and there are no records of his date and cause of death.

Black Inventors - The Complete List of Genius Black American (African American) Inventors, Scientists and Engineers with Their Revolutionary Inventions That Changed the World and Impacted the History - Part One

Countless important contributions to STEM have come from genius Black Americans. They range from revolutionary cancer research to the humble ice cream scoop.

Place of Birth: Valladolid, Mexico

Date of Birth: September 30, 1765

José María Morelos y Pavón was born in the city of Valladolid, today Morelia, on September 30, 1765. Born to a humble family, at an early age he learned to read and write from his mother.

He was a Mexican priest and revolutionary rebel leader during the independence of Mexico.

On September 14, 1813, he drafted and presented the historical document "Sentiments of the Nation", in which section 15 highlights the importance of eliminating slavery and the distinction of caste, on the basis that all are equal.

José María Morelos officially decreed in Mexico the equality between Spaniards, Indians, Creoles, mestizos and members of the different castes.

Source - http://www.oas.org/en/media_ce...-african-descent.asp

Why I’ve made it my mission to teach others about Prince Hall

Story by Danielle Allen, Source - https://www.theatlantic.com/ma...source=pocket-newtab

/media/img/2021/02/09/WEL_Allen_PrinceHallStillOpenerWithFraming/original.png)

Massachusetts abolished enslavement before the Treaty of Paris brought an end to the American Revolution, in 1783. The state constitution, adopted in 1780 and drafted by John Adams, follows the Declaration of Independence in proclaiming that all “men are born free and equal.” In this statement Adams followed not only the Declaration but also a 1764 pamphlet by the Boston lawyer James Otis, who theorized about and popularized the familiar idea of “no taxation without representation” and also unequivocally asserted human equality. “The Colonists,” he wrote, “are by the law of nature free born, as indeed all men are, white or black.” In 1783, on the basis of the “free and equal” clause in the 1780 Massachusetts Constitution, the state’s chief justice, William Cushing, ruled enslavement unconstitutional in a case that one Quock Walker had brought against his enslaver, Nathaniel Jennison.

Many of us who live in Massachusetts know the basic outlines of this story and the early role the state played in standing against enslavement. But told in this traditional way, the story leaves out another transformative figure: Prince Hall, a free African American and a contemporary of John Adams. From his formal acquisition of freedom, in 1770, until his death, in 1807, Hall helped forge an activist Black community in Boston while elevating the cause of abolition to new prominence. Hall was the first American to publicly use the language of the Declaration of Independence for a political purpose other than justifying war against Britain. In January 1777, just six months after the promulgation of the Declaration and nearly three years before Adams drafted the state constitution, Hall submitted a petition to the Massachusetts legislature (or General Court, as it is styled) requesting emancipation, invoking the resonant phrases and founding truths of the Declaration itself.

Here is what he wrote (I’ve put the echoes of the Declaration of Independence in italics):

The petition of A Great Number of Blackes detained in a State of Slavery in the Bowels of a free & christian Country Humbly shuwith that your Petitioners Apprehend that Thay have in Common with all other men a Natural and Unaliable Right to that freedom which the Grat — Parent of the Unavese hath Bestowed equalley on all menkind and which they have Never forfuted by Any Compact or Agreement whatever — but thay wher Unjustly Dragged by the hand of cruel Power from their Derest frinds and sum of them Even torn from the Embraces of their tender Parents — from A popolous Plasant And plentiful ****ry And in Violation of Laws of Nature and off Nations And in defiance of all the tender feelings of humanity Brough hear Either to Be sold Like Beast of Burthen & Like them Condemnd to Slavery for Life.

In this passage, Hall invokes the core concepts of social-contract theory, which grounded the American Revolution, to argue for an extension of the claim to equal rights to those who were enslaved. He acknowledged and adopted the intellectual framework of the new political arrangements, but also pointedly called out the original sin of enslavement itself.

Hall’s memory was vigorously kept alive by members and archivists of the Masonic lodge he founded, and his name can be found in historical references. But his life has attracted fresh attention in recent years from scholars and community leaders, both because he deserves to be widely known and celebrated and because inserting his story into the tale of the country’s founding exemplifies the promise of an integrated way of studying and teaching history. It’s hard enough to shine new light on an African American figure who has been long in the shadows, one who in important ways should be considered an American Founder. It can prove far more difficult to trace an individual’s “relationship tree” and come to understand that person, in a granular and even cinematic way, in the full context of his or her own society: family, school, church, civic organizations, commerce, government. Doing so—especially for figures and communities that have been overlooked—gives us a chance to tell a whole story, to weave together multiple perspectives on the events of our political founding into a single, joined tale. It also provides an opportunity to draw out and emphasize the agency of people who experienced oppression and domination. In the case of Prince Hall, the process of historical reconstruction is still under way.

From the October 2020 issue: Danielle Allen on the flawed genius of the Constitution

When I was a girl, I used to ask what there was to know about the experience of being enslaved—and was told by kind and well-meaning teachers that, sadly, the lack of records made the question impossible to answer. In fact, the records were there; we just hadn’t found them yet. Historical evidence often turns up only when one starts to look for it. And history won’t answer questions until one thinks to ask them.

John Adams and Prince Hall would have passed each other on the streets of Boston. They almost certainly were aware of each other. Hall was no minor figure, though his early days and family life are shrouded in some mystery. Probably he was born in Boston in 1735 (not in England or Barbados, as some have suggested). It is possible that he lived for a period as a freeman before he was formally emancipated. He may have been one of the thousands of African Americans who fought in the Continental Army; his son, Primus, certainly was. As a freeman, Hall became for a time a leatherworker, passed through a period of poverty, and then ultimately ran a shop, from which he sold, among other things, his own writings advocating for African American causes. Probably he was not married to every one of the five women in Boston who were married to someone named Prince Hall in the years between 1763 and 1804, but he may have been. Whether he was married to Primus’s mother, a woman named Delia, is also unclear. Between 1780 and 1801, the city’s tax collectors found their way to some 1,184 different Black taxpayers. Prince Hall and his son appear in those tax records for 15 of those 21 years, giving them the longest period of recorded residence in the city of any Black person we know about in that era. The DePaul University historian Chernoh M. Sesay Jr.’s excellent dissertation, completed in 2006, provides the most thorough and rigorously analyzed academic review of Hall’s biography that is currently available. (The dissertation, which I have drawn on here, has not yet been published in full, but I hope it will be.)

Hall was a relentless petitioner, undaunted by setbacks. When Hall submitted his 1777 petition, co-signed by seven other free Black men, to the Massachusetts legislature, he was building on the efforts of other African Americans in the state to abolish enslavement. In 1773 and 1774, African Americans from Bristol and Worcester Counties as well as Boston and its neighboring towns put forward six known petitions and likely more to this end. Hall led the formation of the first Black Masonic lodge in the Americas, and possibly in the world. The purpose of forming the lodge was to provide mutual aid and support and to create an infrastructure for advocacy. Fourteen men joined Hall’s lodge almost surely in 1775, and in the years from then until 1784, records reveal that 51 Black men participated in the lodge. Through the lodge’s history, one can trace a fascinating story of the life of Boston’s free Black community in the final decades of the 18th century.

Why did Hall choose Freemasonry as one of his life’s passions? Alonza Tehuti Evans, a former historian and archivist of the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of the District of Columbia, took up that question in a 2017 lecture. Hall and his fellow lodge members, he explained, recognized that many of the influential people in Boston—and throughout the colonies—were deeply involved in Freemasonry. George Washington is a prominent example, and symbolism that resonates with Masonic meaning adorns the $1 bill to this day. Hall saw entrance into Freemasonry as a pathway to securing influence and a network of supporters.

Hall submitted a petition to the Massachusetts legislature requesting emancipation, invoking the resonant phrases and founding truths of the Declaration of Independence.

In a world without stable passports or identification documents, participation in the order could provide proof of status as a free person. It offered both leverage and legitimacy—as when Prince Hall and members of his lodge, in 1786, offered to raise troops to support the commonwealth in putting down Shays’s Rebellion.

In the winter and spring of 1788, Hall was leading a charge in Boston against enslavers who made a practice of using deception or other means to kidnap free Black people, take them shipboard, and remove them to distant locations, where they would be sold into enslavement. He submitted a petition to the Massachusetts legislature seeking aid—asking legislators to “do us that justice that our present condition requires”—and publicized his petition in newspapers in Virginia, New York, Pennsylvania, and Vermont.

In the summer of that year, a newspaper circulated an extract of a letter from a prominent white Bostonian who had assisted Hall on this very matter. The unnamed author of the letter reports that he had been visited by a group of free Black men who had been kidnapped in Boston and had recently been emancipated and returned to the city. They were escorted to his house by Hall, and they told the story of their emancipation. One of the men who had been kidnapped was a member of Hall’s Masonic lodge. Carried off to the Caribbean and put on the auction block, the kidnapped men found that the merchant to whom they were being offered was himself a Mason. Mutual recognition of a shared participation in Freemasonry put an end to the transaction and gave them the chance to recover their freedom.

Watch: Atlantic writers will bring the “Inheritance” project to life on February 18

Prince Hall’s work on abolition and its enforcement was just the beginning of a lifetime of advocacy. Disillusioned by how hard it was to secure equal rights for free Black men and women in Boston, he submitted a petition to the Massachusetts legislature seeking funds to assist him and other free Blacks in emigrating to Africa. That same year, he also turned his energies to advocating for resources for public education. Through it all, his Masonic membership proved both instrumental and spiritually valuable.

Founding the lodge had not been easy. Although Hall and his fellows were most likely inducted into Freemasonry in 1775, they were never able to secure a formal charter for their lodge from the other lodges in Massachusetts: Prejudice ran strong. Hall and his fellows had in fact probably been inducted by members of an Irish military lodge, planted in Boston with the British army, who had proved willing to introduce them to the mysteries of the order. Hall’s lodge functioned as an unofficial Masonic society—African Lodge No. 1—but received a formal charter only after a request was sent to England for a warrant. The granting of a charter by the Grand Lodge of England finally arrived in 1787.

In seeking this charter, Hall had written to Masons in England, lamenting that lodges in Boston had not permitted him and his fellows a full charter but had granted a permit only to “walk on St John’s Day and Bury our dead in form which we now enjoy.” Hall wanted full privileges, not momentary sufferance. In this small detail, though, we gain a window into just how important even the first steps toward Masonic privileges were. In the years before 1783 and full abolition of enslavement in Massachusetts, Black people in the state were subjected to intensive surveillance and policing, as enslavers sought to keep their human property from slipping away into the world of free Blacks. Membership in the Masons was like a hall pass—an opportunity to have a parade as a community, to come out and step high, without harassment. That’s what it meant to walk on Saint John’s Day—June 24—and to hold funeral parades for the dead.

Whether that stepping-out day remained June 24 is unclear. As Sesay writes, “Boston blacks, including Prince Hall, first applied to use Faneuil Hall in 1789 to hear an ‘African preacher.’ On February 25, 1789, the Selectmen accepted the application of blacks to use Faneuil Hall for ‘public worship.’ ” By 1820, the walk on Saint John’s Day appears to have become African Independence Day and was celebrated on July 14, Bastille Day, much to the displeasure of at least one newspaper. An unattributed column in the New-England Galaxy and Masonic Magazine complained about the annual parade in recognizably racist tones (the mention of “Wilberforce” at the end is a reference to William Wilberforce, the British campaigner against enslavement):

This is the day on which, for unaccountable reasons or for no reasons at all, the Selectmen of Boston, permit the town to be annually disturbed by a mob of negroes … The streets through which this sable procession passes are a scene of noise and confusion, and always will be as long as the thing is tolerated. Quietness and order can hardly be expected, when five or six hundred negroes, with a band of music, pikes, swords, epaulettes, sashes, cocked hats, and standards, are marching through the principal streets. To crown this scene of farce and mummery, a clergyman is mounted in their pulpit to harangue them on the blessings of independence, and to hold up for their admiration the characters of “Masser Wilberforce and Prince Hall.”

Well after Hall’s death, the days for stepping out continued in Boston—an expression of freedom and the claiming of a rightful place in the polity. The lodge that Hall founded continued too. It is the oldest continuously active African American association in the U.S., with chapters now spread around the country. Its work in support of public education has endured. In the 20th century the Prince Hall Freemasons made significant contributions to the NAACP, in many places hosting the first branches of the organization. In the 1950s alone, the group donated more than $400,000 to the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (equivalent to millions of dollars today). Thurgood Marshall was a member.

/media/img/posts/2021/01/WEL_Allen_PrinceHallSpot/original.png)

For all of what we now know to be Prince Hall’s importance, I learned of him only recently. In 2015 the National Archives held a conference about the Declaration of Independence, inspired by my own research on the document. At the conference, another colleague presented a paper on how abolitionists had been the first people to make use of the Declaration for political projects other than the Revolution itself. A few months earlier I had come across the passage from Hall’s 1777 petition that I shared above, and that so beautifully resonates with the Declaration; at that conference, I suddenly learned the important political context in which it fit. I had published a book on the Declaration of Independence—Our Declaration—in 2014, but until the spring of 2015, I had never heard of Hall.

Yet I have been studying African American history since childhood. When I was in high school, my school didn’t do anything to celebrate Black History Month. My father encouraged me to take matters into my own hands and propose to the school that I might curate a weekly exhibit on one of the school’s bulletin boards. The school was obliging. It offered me the one available bulletin board—in a dark corner in the farthest remove of the school’s quads. This was not the result of malice, just of a lack of attention to the stakes. But I was glad to have access to that bulletin board, and I dutifully filled it with pictures of people like Carter G. Woodson and Mary McLeod Bethune and Thurgood Marshall, and with excerpts from their writings.

Jemele Hill: Curt Flood belongs in the Hall of Fame

I am deeply aware of how much historical treasure about Black America is hidden, and have been actively trying to seek it out. While I was on the faculty of the University of Chicago, I helped found the Black Metropolis Research Consortium, a network of archival organizations in Chicago dedicated to connecting “all who seek to document, share, understand and preserve Black experiences.” And while I was at Chicago—somewhat in the spirit of that old bulletin board—I curated an exhibit for the special-collections department of the campus library on the 45 African Americans who’d earned a doctorate at the university prior to 1940—the largest number of doctorates awarded to African Americans up to that time by any institution in the world. Even so, I had not known about Prince Hall.

Having discovered Hall at the ridiculous age of 43, I have since made it a mission to teach others about him. At Harvard’s Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics, we have undertaken a major initiative to develop civic-education curricula and resources. Among the largest projects is a year-long eighth-grade course called “Civic Engagement in Our Democracy.” One of the units in that course is centered on Hall’s life. Through him and his exploration of the meaning of social contracts and natural rights, and of opportunity and equality, we teach the philosophical foundations of democracy, reaching through Hall to texts that he also drew on, and whose authors are required reading for eighth graders in Massachusetts—for instance, Aristotle, Locke, and Montesquieu. These writers and thinkers were important figures to Freemasons in Hall’s time.

Too much treasure remains buried, living mainly in oral histories, not yet integrated into our full shared history of record. That history can strike home in unexpected ways. Not long ago, I was talking with my father about Prince Hall and the curriculum we were developing. His ears pricked up. Only then did I learn that my grandfather, too, had been a member of the Prince Hall Freemasons.

Next: Read Clint Smith on the Americans who survived slavery—and were almost forgotten.

Jeez, DG! There's so much to read? Why don't you just refer to anyone interested? Oh, go ahead anyway! Never mind me! I spend more time sttacking kant and.his PPP affliction!

Agreed, all this stuff is like a Masters thesis but thanks DG. Can we now return to the more mundane stuff like how Clive Thomas ripped off APNU for millions and couldn't produce a single PPP criminal?

@lil boy posted:Agreed, all this stuff is like a Masters thesis but thanks DG. Can we now return to the more mundane stuff like how Clive Thomas ripped off APNU for millions and couldn't produce a single PPP criminal?

Did he? Clive was always a quiet one at QC! Still waters?

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/marian-anderson-142620412-59e4c6bd054ad900118d1160.jpg)

Contralto Marian Anderson is considered one of the most important singers of the 20th century. Known for her impressive three-octave vocal range, she performed widely in the U.S. and Europe, beginning in the 1920s. She was invited to perform at the White House for President Franklin Roosevelt and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt in 1936, the first African American so honored. Three years later, after the Daughters of the American Revolution refused to allow Anderson to sing at a Washington, D.C. gathering, the Roosevelts invited her to perform on the steps of the Lincon Memorial.

Anderson continued to sing professionally until the 1960s when she became involved in politics and civil rights issues. Among her many honors, Anderson received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1963 and a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1991.

10 of the Most Important Black Women in U.S. History, By Jone Johnson Lewis, Updated December 12, 2020, Source - https://www.thoughtco.com/nota...erican-women-4151777

Black women have made important contributions to the United States throughout its history. However, they are not always recognized for their efforts, with some remaining anonymous and others becoming famous for their achievements. In the face of gender and racial bias, Black women have broken barriers, challenged the status quo, and fought for equal rights for all. The accomplishments of Black female historical figures in politics, science, the arts, and more continue to impact society.

By Kallie Szczepanski, Updated July 03, 2019, Source - https://www.thoughtco.com/invention-of-paper-195265

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-626727880-5bb3b60346e0fb0026932f12.jpg) Paper Mill., Robert Essel NYC / Getty Images

Paper Mill., Robert Essel NYC / Getty Images

Try to imagine life without paper. Even in the era of emails and digital books, paper is all around us. Paper is in shopping bags, money, store receipts, cereal boxes, and toilet paper. We use paper in so many ways every day. So, where did this marvelously versatile material come from?

According to ancient Chinese historical sources, a court eunuch named Ts'ai Lun (or Cai Lun) presented the newly-invented paper to the Emperor Hedi of the Eastern Han Dynasty in 105 CE. The historian Fan Hua (398-445 CE) recorded this version of events, but archaeological finds from western China and Tibet suggest that paper was invented centuries earlier

Samples of even more ancient paper, some of it dating to c. 200 BCE, have been unearthed in the ancient Silk Road cities of Dunhuang and Khotan, and in Tibet. The dry climate in these places allowed the paper to survive for up to 2,000 years without entirely decomposing. Amazingly, some of this paper even has ink marks on it, proving that ink was invented much earlier than historians had supposed.

Of course, people in various places around the world were writing long before the invention of paper. Materials such as bark, silk, wood, and leather functioned in a similar way to paper, although they were either much more expensive or heavier. In China, many early works were recorded on long bamboo strips, which were then bound with leather straps or string into books.

People world-wide also carved very important notations into stone or bone, or pressed stamps into wet clay and then dried or fired the tablets to preserve their words. However, writing (and later printing) required a material that was both cheap and lightweight to become truly ubiquitous. Paper fit the bill perfectly.

Early paper-makers in China used hemp fibers, which were soaked in water and pounded with a large wooden mallet. The resulting slurry was then poured over a horizontal mold; loosely-woven cloth stretched over a framework of bamboo allowed the water to drip out the bottom or evaporate, leaving behind a flat sheet of dry hemp-fiber paper.

Over time, paper-makers began to use other materials in their product, including bamboo, mulberry and different types of tree bark. They dyed paper for official records with a yellow substance, the imperial color, which had the added benefit of repelling insects that might have destroyed the paper otherwise.

One of the most common formats for early paper was the scroll. A few long pieces of paper were pasted together to form a strip, which was then wrapped around a wooden roller. The other end of the paper was attached to a thin wooden dowel, with a piece of silk cord in the middle to tie the scroll shut.

From its point of origin in China, the idea and technology of paper-making spread throughout Asia. In the 500s CE, artisans on the Korean Peninsula began to make paper using many of the same materials as Chinese paper-makers. The Koreans also used rice straw and seaweed, expanding the types of fiber available for paper production. This early adoption of paper fueled the Korean innovations in printing, as well. Metal movable type was invented by 1234 CE on the peninsula.

Around 610 CE, according to legend, the Korean Buddhist monk Don-Cho introduced paper-making to the court of Emperor Kotoku in Japan. Paper-making technology also spread west through Tibet and then south into India.

In 751 CE, the armies of Tang China and the ever-expanding Arab Abbasid Empire clashed in the Battle of Talas River, in what is now Kyrgyzstan. One of the most interesting repercussions of this Arab victory was that the Abbasids captured Chinese artisans, including master paper-makers like Tou Houan, and took them back to the Middle East.

At that time, the Abbasid Empire stretched from Spain and Portugal in the west through North Africa to Central Asia in the east, so knowledge of this marvelous new material spread far and wide. Before long, cities from Samarkand (now in Uzbekistan) to Damascus and Cairo had become centers of paper production.

In 1120, the Moors established Europe's first paper mill at Valencia, Spain (then called Xativa). From there, this Chinese invention passed to Italy, Germany, and other parts of Europe. Paper helped spread knowledge, much of which was gleaned from the great Asian culture centers along the Silk Road, that enabled Europe's High Middle Ages.

Meanwhile, in East Asia, paper was used for an enormous number of purposes. Combined with varnish, it became beautiful lacquer-ware storage vessels and furniture. In Japan, the walls of homes were often made of rice-paper. Besides paintings and books, paper was made into fans, umbrellas, even highly effective armor. Paper truly is one of the most wonderful Asian inventions of all time.

@Former Member posted:Marian Anderson (Feb. 27, 1897–April 8, 1993)

Contralto Marian Anderson is considered one of the most important singers of the 20th century. Known for her impressive three-octave vocal range, she performed widely in the U.S. and Europe, beginning in the 1920s. She was invited to perform at the White House for President Franklin Roosevelt and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt in 1936, the first African American so honored. Three years later, after the Daughters of the American Revolution refused to allow Anderson to sing at a Washington, D.C. gathering, the Roosevelts invited her to perform on the steps of the Lincon Memorial.

Anderson continued to sing professionally until the 1960s when she became involved in politics and civil rights issues. Among her many honors, Anderson received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1963 and a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1991.

10 of the Most Important Black Women in U.S. History, By Jone Johnson Lewis, Updated December 12, 2020, Source - https://www.thoughtco.com/nota...erican-women-4151777

Black women have made important contributions to the United States throughout its history. However, they are not always recognized for their efforts, with some remaining anonymous and others becoming famous for their achievements. In the face of gender and racial bias, Black women have broken barriers, challenged the status quo, and fought for equal rights for all. The accomplishments of Black female historical figures in politics, science, the arts, and more continue to impact society.

@Former Member posted:Marian Anderson (Feb. 27, 1897–April 8, 1993)

Contralto Marian Anderson is considered one of the most important singers of the 20th century. Known for her impressive three-octave vocal range, she performed widely in the U.S. and Europe, beginning in the 1920s. She was invited to perform at the White House for President Franklin Roosevelt and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt in 1936, the first African American so honored. Three years later, after the Daughters of the American Revolution refused to allow Anderson to sing at a Washington, D.C. gathering, the Roosevelts invited her to perform on the steps of the Lincon Memorial.

Anderson continued to sing professionally until the 1960s when she became involved in politics and civil rights issues. Among her many honors, Anderson received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1963 and a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1991.

10 of the Most Important Black Women in U.S. History, By Jone Johnson Lewis, Updated December 12, 2020, Source - https://www.thoughtco.com/nota...erican-women-4151777

Black women have made important contributions to the United States throughout its history. However, they are not always recognized for their efforts, with some remaining anonymous and others becoming famous for their achievements. In the face of gender and racial bias, Black women have broken barriers, challenged the status quo, and fought for equal rights for all. The accomplishments of Black female historical figures in politics, science, the arts, and more continue to impact society.

I would have refused to listen to her, too! With all the positionings of her mouth to sing a song that my girl Ella would have blazed through effortlessly! Ella's singing is like musical honey being poured into my ears! She calms and soothes me! Ella who? Why, the Fiirst Lady of Song, Miss Ella Fitzgerald! My queen!

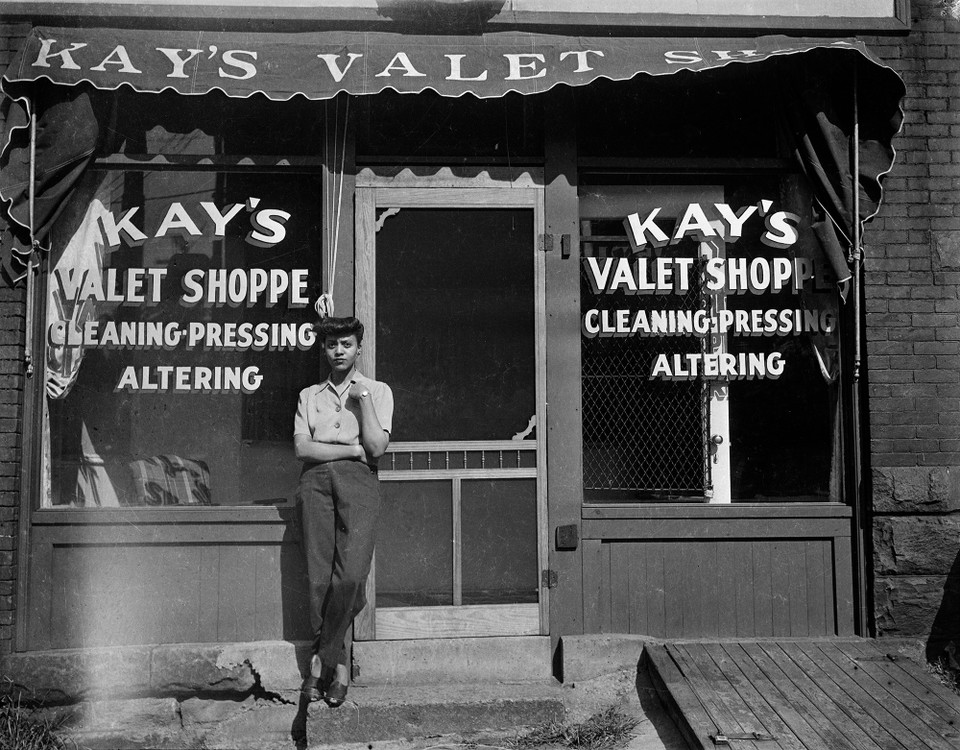

Charles “Teenie” Harris captured at least 125,000 people during the 40 years he documented Black life for The Pittsburgh Courier.

Story by Damon Young, March 2021 Issue, Source - The Atlantic - https://www.theatlantic.com/ma...s-pittsburgh/617789/

This article is part of “Inheritance,” a project about American history and Black life.

Photographs by Charles “Teenie” Harris

A thing you should probably know about Black Pittsburgh’s relationship with Teenie is that we love to lie about him. Charles “Teenie” Harris captured at least 125,000 people in the tens of thousands of photos he took during the 40 years he documented Black life for The Pittsburgh Courier. Thirty-five of those photos are now part of an ongoing exhibition at the Carnegie Museum of Art. To hear it today, everybody’s grandma was shot by him, everybody’s great-uncle played spades against him, and everybody’s second cousin’s third cousin got lit at the Crawford Grill with him. This is what happens when someone is magic like that. When the shadow of someone’s work is so mammoth—such a part of how we see and love and regard and remember ourselves—we insert ourselves in its shade.

In the shot above, from 1951, 45 or so people stand outside the Hill District studio of the iconoclastic DJ Mary Dee Dudley. Dudley was America’s first Black female DJ, and her shows became impromptu block parties as crowds gathered in front of the studio’s storefront windows to request songs, see Mary Dee, and be seen. The Hill of the early 20th century was an internationally renowned hub of Black culture, frequented by Duke and Satchmo, home to Greenlee Field and Madam C. J. Walker’s Lelia College of Beauty Culturists, and later immortalized by August Wilson’s Century Cycle.

Woman wearing pants standing outside of Kay's Valet Shoppe on Junilla Street in the Hill District, ca. 1938–1945 (Charles “Teenie” Harris Archive / Carnegie Museum of Art)

Woman wearing pants standing outside of Kay's Valet Shoppe on Junilla Street in the Hill District, ca. 1938–1945 (Charles “Teenie” Harris Archive / Carnegie Museum of Art)

Men playing checkers in front of Babe's Place, Hill District, June 1949 (Charles “Teenie” Harris Archive / Carnegie Museum of Art)

Men playing checkers in front of Babe's Place, Hill District, June 1949 (Charles “Teenie” Harris Archive / Carnegie Museum of Art)

n the late ’50s, many of the Hill District living rooms, rib spots, corner stores, stoops, schools, basements, backyards, barstools, banks, and barbershops canonized by Teenie’s lens were wiped away to build an arena that no longer exists. By the time he died, in 1998, at nearly 90 years old, the population of the Hill had dropped from 50,000 to 12,000.

Another thing you should probably know about Black Pittsburgh’s relationship with Teenie is that those lies tell the truth. How did—how do—we survive in a city considered one of America’s “Most Livable” but that’s somehow one of the least livable for us? I don’t know. But I do know that community, for Black Pittsburghers, is a proper noun and a shelter from the city. Even if we didn’t actually find our way into his orbit, when Teenie caught one of us, he caught all of us.

Damon Young is a writer in Pittsburgh and the author of What Doesn’t Kill You Makes You Blacker.

Access to this requires a premium membership.