Like I asked before, DG, what is the colour of brains? Deny people learning or opportunities makes you superior or does your ability to inflict death or injury do that? Sh*t, they go back to heaven, the spirit or energy world, before you and unlike you, they are no longer concerned with the physical demands of a body! No need for food, drink, clothing or shelter or fing or jealousy! And you're still here looking on, interfering to help only where necessary!

Hooray for death! It's unappreciated!

These three women (Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi) are the founders of Black Lives Matter. The organization,

These three women (Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi) are the founders of Black Lives Matter. The organization,

Michael Ochs Archives via Getty Images

Michael Ochs Archives via Getty Images Doug Pensinger via Getty Images

Doug Pensinger via Getty Images

Stephane Cardinale - Corbis/Corbis Entertainment/Getty Images

Stephane Cardinale - Corbis/Corbis Entertainment/Getty Images

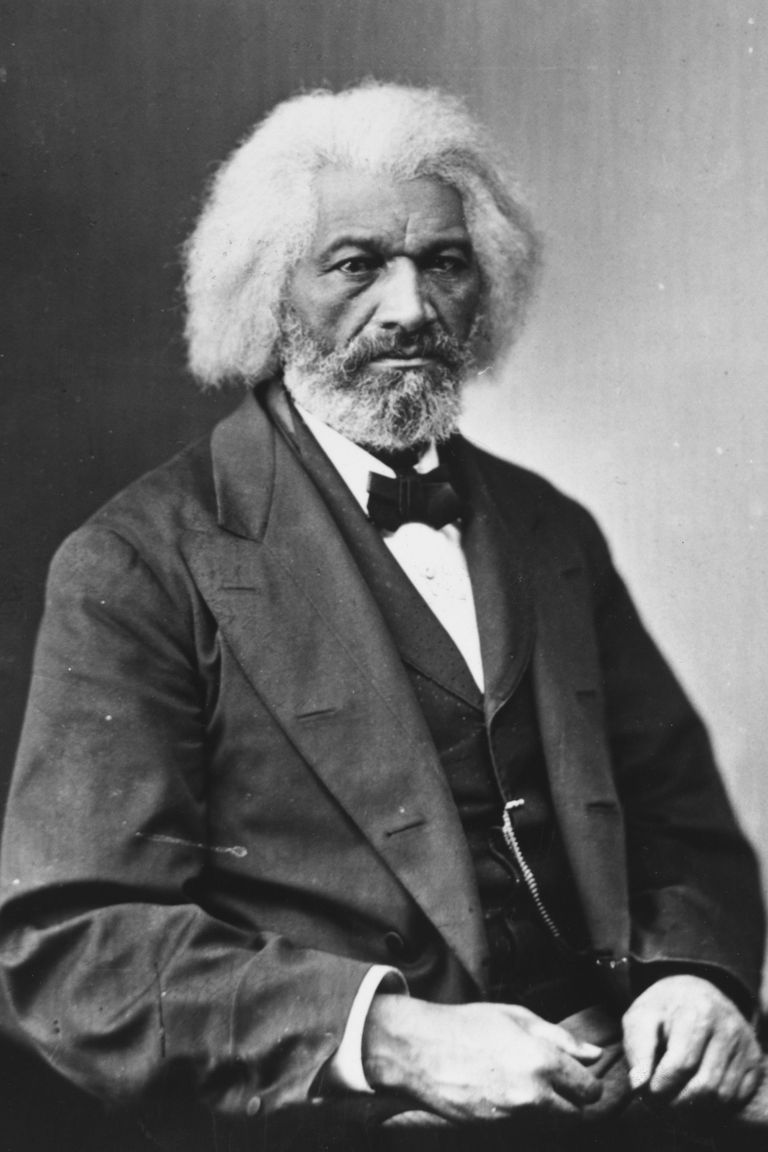

Library of Congress

Library of Congress A funeral held in July 1945 for two victims of the Ku Klux Klan, George Dorsey and his sister, Dorothy Dorsey Malcolm, of Walton County, Georgia, held at the Mt. Perry Baptist Church Sunday. Photo from Bettman via Getty.

A funeral held in July 1945 for two victims of the Ku Klux Klan, George Dorsey and his sister, Dorothy Dorsey Malcolm, of Walton County, Georgia, held at the Mt. Perry Baptist Church Sunday. Photo from Bettman via Getty. A white lynch mob in Shelbyville, Tennessee, in 1941. Photo from Bettmann via Getty.

A white lynch mob in Shelbyville, Tennessee, in 1941. Photo from Bettmann via Getty. The National Memorial For Peace And Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, commemorates the victims of lynching. Photo by Bob Miller / Getty Images.

The National Memorial For Peace And Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, commemorates the victims of lynching. Photo by Bob Miller / Getty Images. Ida B. Wells, the great documentarian of the lynching era, in 1920. Photo from the Chicago History Museum / Getty Images.

Ida B. Wells, the great documentarian of the lynching era, in 1920. Photo from the Chicago History Museum / Getty Images.