BOLLYWOOD TRAGEDY KING:

DILIP KUMAR

THREE KINGS OF BOLLYWOOD DILIP KUMAR , AMITABH BACCHAN, SHARUKH KHAN:

BOLLYWOOD TRAGEDY KING:

DILIP KUMAR

THREE KINGS OF BOLLYWOOD DILIP KUMAR , AMITABH BACCHAN, SHARUKH KHAN:

Jan 18, 2014, 12.01 AM IST

AAN

(“Pride&rdquo![]() , Hindi, 1952, 162 minutes

, Hindi, 1952, 162 minutes

Produced and directed by Mehboob Khan

Story: R. S. Chaudhary; Dialogs: S. Ali Raza; Lyrics: Shakil Badayuni; Music: Naushad; Cinematography: Faredoon S. Irani; Art Director: M. R. Acharekar; Sets: D. R. Jadhav; Costumes: Fazal Din, Chagan Jivvan, Alla Ditta

AAN is said to have been India’s first technicolor feature, and director Khan went wild with the possibilities, crafting a highly surreal swashbuckler about a princely kingdom that lies, visually speaking, somewhere between Rajasthan and mad King Ludwig’s Bavaria. Though there are echoes here and there of the real excesses and hybrid architectural fantasies of India’s pre-independence maharajas, as well as themes glorifying peasant resistance and social egalitarianism, mostly this is an over-the-top operatic fairytale that looks, at times, like Disney animation come to life—though Disney would not have dared the out-front eroticism and fashion and footwear fetishism that permeates Mehboob’s mise-en-scene. There is clear influence of Hollywood fantasy adventures such as THE THIEF OF BAGDAD (both the 1924 silent version with Douglas Fairbanks and the 1940 sound version with Sabu were well received in India), as well as of imperial Roman spectacles. Indeed, there are few stops that Khan does not eventually pull out, throwing in a camel stampede, a Dungeons-and-Dragons prison complete with rampaging lions, a Joan of Arc-like burning at the stake, and a floridly orientalist dream sequence that looks like something ballet impresario Serge Diaghilev might have hallucinated on LSD.

Nevertheless, those familiar with the director’s most famous film, MOTHER INDIA (1957), will also recognize his fondness for sunsets, vast Deccani landscapes (juxtaposed unconcernedly with obvious soundstage simulacra), a Soviet-influenced populism (exemplified by busty women silhouetted against bullock-carts), florid poetic dialog full of Urdu conceits (lover as moth, beloved as flame, etc.), and music, music, music. This is from the famous Badayuni and Naushad team, is all pervasive (twelve songs) and generally excellent.

So is the casting, with Dilip Kumar at the height of his romantic charm as the roguish peasant leader Jai Tilak, and the Bombay Jewish actress Nadira (better known for roles as modernized vixens—e.g., Maya in 1955’s SHRI 420) as a terminally proud princess, who favors a semi-dominatrix wardrobe and keeps one eyebrow severely arched throughout most of the movie. Naturally, the farm boy falls for the ice queen big time and much of the film revolves around his taming of this shrew (hint: when she begins to appear in saris, you know it’s working), against a backdrop of palace intrigue and rustic exuberance.

An opening narration, against a shot of Jai (Kumar) plowing his field, sketches an idealized Nation in which sturdy yeomen till the land in peacetime but trade their agricultural tools for swords when war threatens—here the community is known as the Haras (historically, this suggests semi-martial landowning castes like the Marathas and Gujars, who have sometimes consolidated their own kingdoms and even empires—though Indian history is hardly the point). The benign Maharaja to whom Jai owes allegiance (Murad), has a cruel younger brother, Prince Shamsher Singh (Premnath), as well as a spirited junior sister (Nadira) given to breaking horses and would-be suitors. Shamsher Singh’s ambitions are as flamboyant as his wardrobe, and he conspires to assassinate the raja—who his subjects believe has gone abroad for medical treatment—and to launch an increasingly despotic regime, signaled by his ranging the countryside in a Cadillac convertible and casting lustful eyes on village belles, especially the headstrong Mangala (Nimmi), who loves Jai. This in itself would be enough to set the two men at odds, but for good measure, Jai (who evidently likes challenges) falls in love with Shamsher’s icy sister, after taming her wild stallion in a tournament. Though she truly appears to hate him (generally a sign, in Hindi cinema, that love is just around the corner), he woos her by dropping in and out of her Sleeping Beauty-art deco castle, stealing her scarf, squirting her with Holi colors, and dispensing double entendres rich in imagery of romantic martyrdom.

Will this approach eventually work? Will Shamsher Singh, after kidnapping Mangala and trying to rape her, finally get his comeuppance? Will the kindly old Maharaja turn out to not actually be dead but just disguised behind a really ridiculous false beard, and actually intent on abolishing the monarchy and instituting Democracy? Use your imagination, or rather, let Mehboob Khan beguile you with his own more frenzied one, as well as his everything-including-the-kitchen-sink approach to visual spectacle. Dilip Kumar, who had by this time earned a reputation as Bombay’s “king of tragedy” and was allegedly beginning to identify too much with his morose characters, is said to have accepted the role of Jai after a psychiatrist advised him to do “lighter” films. Indeed, the good doctor should have been well pleased by AAN, and you should be too.

[For those who don’t know Hindi, the one drawback to the otherwise good quality Eros Entertainment DVD of AAN is that the songs—which here comprise nearly fifty per cent of the running time—are unsubtitled.]

(1954, Hindi, 144 minutes)

Directed by Mehboob

Story: S. Ali Raza, Mehrish, S. K. Kalla, B. S. Ramiah; Dialogs: Agha Jani Kashmiri, S. Ali Raza; Lyrics: Shakeel Badayuni; Music: Naushad; Choreography: Sita Devi; Cinematography: Faredoon A. Irani; Art Direction: V. H. Palnitkar; Sets: D. R. Jadhav

In a plot that bears more than a passing resemblance to that of BABUL (1950), Dilip Kumar plays Amar, a rich and successful young lawyer who is known for his high ideals and willingness to assist local villagers, especially in their dealings with Sankat (literally, “affliction,” a local landlord and bully, played by Jayant). Sonia (Nimmi) is an innocent and vivacious village girl who talks to animals and birds and dances unselfconsciously by babbling streams—in short, the Shakuntala type (and the role played by Nargis in BABUL). She falls for Amar one day when her dupatta blows off and lands on his head, leading to a teasing exchange. But when the lawyer sustains a cut finger, Sonia spontaneously rips her threadbare scarf to bandage it—a motif that invokes a famous Mahabharata tale in which Draupadi does the same for Krishna, thus putting him in her debt. Indeed, Amar’s little flesh wound, and the possibility that it will “infect” him further, dominates the ensuing dialog back at his law office. And well it might, for although Amar soon becomes betrothed to, and falls in love with, the sophisticated Anju (Madhubala), the daughter of a local zamindar and his own father’s choice for him, and although Sonia is likewise engaged, by her scheming stepmother, to the dreaded Sankat, Amar’s prior link with the village girl refuses to go away. And one Dark and Stormy Night, when the dripping wet Sonia takes shelter in Amar’s mansion while fleeing the wrath of Sankat, the young lawyer loses control of himself.

Such little cross-class indiscretions, when elite men take advantage of rustic and especially low-caste girls, are known to be routine enough in rural areas, and generally hushed up with money or intimidation. What’s different here is that Amar is a man of both principle and cowardice—a combination that might strike some viewers as odd in a “hero” (the Encyclopaedia of Indian Cinema observes that the film was not a commercial hit, "possibly because the audience refused to accept Dilip Kumar in a negative role")—who suffers crushing guilt yet cannot bring himself to openly confess his indiscretion. One may assume that he is constrained by social circumstance: by the impossible class gulf that divides him from Sonia, and by the fact that an admission of guilt would wreck his reputation, his career, and his hopes of marrying his beloved Anju. For her part, Sonia bears his secret (and, it soon turns out, his child) with a slightly-loopy stoicism and puppy-like loyalty. Both Anju and Sankat gradually begin to suspect that something is amiss, and Amar repeatedly comes close to fessing up, especially when dragged to the local Krishna temple by Anju, who is herself an idealist and champion of the downtrodden, where a bhajan informs him that “This is the temple of justice, the house of God; say what you have to say—what is there to fear?” But many plot turns, each accompanied by a memorable Naushad song (nine in all, and entirely sung by the female characters), precede the final revelation.

The cinematography is notable for its use of light and shadow, ingenious framing, Mehboob’s trademark sunset silhouettes, and frequent and lingering closeups of the principals’ tormented faces. Ornate, surreal sets (typical of this period) are likewise used to good effect. Like BABUL, this is an operatic “he done her wrong” fantasy that delights in heavyhanded symbolism (shattered windows, torn dupattas, flickering lamps) and mythological allusions: the opening reference to Draupadi is renewed during Sonia’s climactic humiliation by angry villagers, when (like the Pandava heroine being disrobed in the Kauravas’ gambling hall) she calls on Krishna for help, and her plea reaches her own “immortal,” Amar.

[The Eros/B4U DVD of AMAR features a generally excellent quality print of the film. Subtitles are also unusually accurate, but are unfortunately missing for the many songs.]

ANDAZ

(“Style,” Hindi, 1949, 148 minutes)

Directed by Mehboob Khan

Story: Shums Lucknavi; Screenplay and dialogs: S. Ali Raza; Music: Naushad; Songs: Majrooh Sultanpuri; Photography: Faredoon A. Irani

Like many films of the immediate post-Independence era, this tragedy of manners focuses, in a darker than usual register, on both the allure and danger of modern western lifestyles and modes of social behavior. Though their allure would appear to be felt by all, their danger is unequally shared between the sexes: since nationalist ideology posits woman as the embodiment of tradition as well as the guardian, through her chastity, of male honor, she incurs the greatest risk in any flirtation with the modern—a flirtation which (given the dictum that her sole God must be her husband) is tantamount to adultery. The suspicion of this sin, nurtured by innocent misunderstandings and repeated failures of communication in a world governed by verbal codes that discourage straightforward speech, lies at the core of the strange and destructive “love triangle” in this film.

As the spoilt only child of a doting millionaire, Neena (Nargis) divides her time between palatial homes in Shimla and Bombay. We first see her in her hill station lodge, being dressed in riding clothes by attentive servants, surrounded by amenities (including a salon-style hair dryer) connoting the last word in westernized luxury. Yet the supplier of all this, Neena’s devoted “Daddy” (Sapru) displays, in their first exchange, a hint of reticence about their lifestyle (complaining of sore limbs from excessive horseback riding in his “old age&rdquo![]() that is suggestive of deeper unease to come. Moreover, in implying that his nineteen-year-old daughter is approaching marriageable age (when she complains that she does not like to ride alone, he quips “That can soon be remedied…” causing her to blush), he also alludes to his traditional responsibility to insure her chastity and supervise her transfer to the oversight of another man. Soon after this, the headstrong Neena loses control of her horse and is rescued by a dashing stranger, Dilip (Dilip Kumar); her horse’s fall to its death from a high cliff prefigures the plight into which the principals will soon plunge, driven by Neena’s heedless disregard of social propriety. For when Dilip introduces himself to Neena’s dad (who has come to the hospital to fetch her after her mishap), we sense a definite chill: the old man appears dismayed by Dilip and Neena’s flirtatious exchange and her invitation to Dilip to come visit them at home. Later, when Dilip sings of his budding love for Neena (Hum aaj kahin dil kho baithe, “Today I lost my heart somewhere&rdquo

that is suggestive of deeper unease to come. Moreover, in implying that his nineteen-year-old daughter is approaching marriageable age (when she complains that she does not like to ride alone, he quips “That can soon be remedied…” causing her to blush), he also alludes to his traditional responsibility to insure her chastity and supervise her transfer to the oversight of another man. Soon after this, the headstrong Neena loses control of her horse and is rescued by a dashing stranger, Dilip (Dilip Kumar); her horse’s fall to its death from a high cliff prefigures the plight into which the principals will soon plunge, driven by Neena’s heedless disregard of social propriety. For when Dilip introduces himself to Neena’s dad (who has come to the hospital to fetch her after her mishap), we sense a definite chill: the old man appears dismayed by Dilip and Neena’s flirtatious exchange and her invitation to Dilip to come visit them at home. Later, when Dilip sings of his budding love for Neena (Hum aaj kahin dil kho baithe, “Today I lost my heart somewhere&rdquo![]() , and she apparently reciprocates with a lovesong of her own (Dar na mohabbat kar le, “Don’t be afraid to fall in love&rdquo

, and she apparently reciprocates with a lovesong of her own (Dar na mohabbat kar le, “Don’t be afraid to fall in love&rdquo![]() , her father begins showing his disapproval, cautioning her that there are standards to which “the world” adheres that are not taught in college (an indication of Neena’s own level of education). Neena pouts and accuses him of holding views “from 150 years back”; in the matter at hand (the question of whether to invite Dilip to her birthday party) she again manages to get her way. Viewers may wonder why her father seems so disapproving of an apparently genteel boy of comparable social status. This mystery lingers until after the old man’s unexpected demise from heart failure. The stricken Neena is helped through this loss by Dilip, whom she rewards by making the manager and co-owner (with her) of her father’s corporate empire: a partnership that appears to Dilip (and to viewers) to promise a yet more consummate merger to come. But his hopes are dashed one day when Neena takes him to the airport to meet Rajan (Raj Kapoor), who has been away in London for several years, yet who is, it turns out, her fiancé and one true love. It gradually becomes clear that Neena’s allusions, in previous coy exchanges with Dilip, to being in love in fact referred to Rajan and not to Dilip.

, her father begins showing his disapproval, cautioning her that there are standards to which “the world” adheres that are not taught in college (an indication of Neena’s own level of education). Neena pouts and accuses him of holding views “from 150 years back”; in the matter at hand (the question of whether to invite Dilip to her birthday party) she again manages to get her way. Viewers may wonder why her father seems so disapproving of an apparently genteel boy of comparable social status. This mystery lingers until after the old man’s unexpected demise from heart failure. The stricken Neena is helped through this loss by Dilip, whom she rewards by making the manager and co-owner (with her) of her father’s corporate empire: a partnership that appears to Dilip (and to viewers) to promise a yet more consummate merger to come. But his hopes are dashed one day when Neena takes him to the airport to meet Rajan (Raj Kapoor), who has been away in London for several years, yet who is, it turns out, her fiancé and one true love. It gradually becomes clear that Neena’s allusions, in previous coy exchanges with Dilip, to being in love in fact referred to Rajan and not to Dilip.

However, such careless words, and the exchanges of looks that accompanied them, have had an unintended effect: Dilip is now hopelessly in love with Neena. The breezy, self-confident Rajan (an early incarnation of the narcissistic husband of Kapoor’s later SANGAM, which will repeat several motifs from this film, including a little wooing scene he performs here using a snakecharmer’s reed-pipe) is at first unaware of these complications, as is Neena herself, who considers Dilip merely a close “friend” (dost). But Dilip is sufficiently tortured by unrequited love to nurture the crazed hope that Neena may yet transfer her affections to him. When Neena and Rajan are finally married, Dilip can restrain himself no longer and, soon after the ceremony, confesses his love to Neena. The horror that this admission inspires in Neena appears to have multiple causes: fear that her husband may learn of Dilip’s love and suspect that she returns it; guilt over the realization that she has inadvertently encouraged Dilip; and dread of her own suppressed attraction (conveyed through her glances and body language) to the intense and sensual Dilip. She attempts to tell her new husband about Dilip’s confession, but Rajan misunderstands her and cockily changes the topic (as always, he thinks she is talking about him!), and the frustrated Neena resorts to various forms of denial: repeatedly professing her love for her “only God,” Rajan, fleeing with him to Shimla and refusing to return to Bombay, and stubbornly urging Dilip to marry her own girlfriend Sheela (Cuckoo), who is herself in love with him. Though uninterested in Sheela and desperate to leave, Dilip remains in Bombay running Neena’s business out of concern that an abrupt departure on his part, so soon after her marriage, might tarnish her reputation. He remains, too, in Neena’s consciousness, haunting her dreams and slowly chilling her relationship with her husband. When a daughter is born to the couple, Neena becomes troubled by Rajan’s adoration of her, fearing that he too, like her own father, will “spoil” the child’s character with excessive indulgence and freedom. Dilip waits until the baby’s first birthday for his own exit, concealing a note to Neena (explaining that he now understands that, as an "Indian woman," she can have only one man in her heart, and that is Rajan) inside a toy he presents as a gift. A power failure during the party affords an opportunity to Neena to give a verbal message to Dilip, likewise begging him to leave, but in the dark she accidentally addresses her own husband with what Rajan now mistakes for a profession of love for Dilip. It’s all downhill from here, as Rajan’s insane jealousy provokes him, through several bouts of grandiose self-pity and biting sarcasm, to frustrate every effort by both his wife and Dilip to clear the record. Eventually, he attempts to kill Dilip with a blow to the head; the resulting concussion causes Dilip to go temporarily insane and to threaten Neena, both violently and sexually. Assailed, in effect, by two madmen, Neena commits a desperate act, resulting in her arrest and dramatic public trial.

Within this grim story, diversion of a sort is provided early on by one Professor Devadas Dharamdas Trivedi (a.k.a. "D.D.T."), a bogus academic with a childhood link to Rajan, who insinuates himself into the household as a freeloader. Trivedi is a classic vidushaka (the comic sidekick of the hero of classical and folk theater): a dim but pretentious Brahman with outspoken opinions and uncontrollable appetites. Here he functions especially effectively as an exaggerated mirror image of the principal characters: like them, he is a creature caught between worlds, wearing a western style suit and solar topee, yet spouting Sanskritized Hindi and denouncing the decadent “foreign” lifestyle of his hosts, even as he greedily partakes of it.

Although voyeuristic delight in the westernized lives of the rich was (and remains) standard in Bombay films, Mehboob seems to dwell with particular intensity on surface signifiers of stylish modernity: Neena’s bob of permed hair, which she languorously fondles while talking to Dilip, her English-style boudoir and lap dog, and the Shimla round of horseback riding, tennis, and big-band soirees. The culturally corrosive effect of such amenities, earlier (hypocritically) decried by the buffoon Trivedi, is (even more ironically and hypocritically) declared by Rajan in his self-pitying speeches during Neena’s trial. Indeed, although Neena is ultimately driven to commit an act of violence, her real “crime” (apart from being involved in a series of misunderstandings, coincidences, and mistimed communications) appears to be her taste for "style". The film implies that there is a slippery slide from such taste to a disastrous non-adherence to norms of feminine modesty and non-assertiveness (displayed in Neena's repeated expressions that she doesn’t care what “worldly people” think about her behavior), and her error in boldly supposing that it is truly possible for a young woman to have a young man as a close “friend” (dost) without him and others getting the wrong idea.

Though the film appears to endorse Neena’s father’s often-recalled warnings about girls keeping within decorous limits, Rajan’s insufferable self-centeredness suggests just how much "good" Indian women may have to put up with (his assault on Dilip follows the latter’s—patently correct—assertion that Rajan has never really understood his own wife). And though the film is at pains to maintain the purity of Neena’s friendship with Dilip (which will eventually be distorted, by Rajan and society at large, into the manipulations of a lustful temptress), it also hints at the possibility of underlying erotic attraction, playing on the often sensually charged word dost. Rajan finally learns—when it is too late—the truth about Neena’s relationship with Dilip, and so presumably has to face his own measure of guilt. Indeed, there is guilt aplenty in this haunting, complex film, which ultimately implicates itself, and all its viewers, in Neena’s “crime”: succumbing to the irresistible attractions of alien “style” (and its attendant promise of new kinds of freedom, especially in male-female relationships), while maintaining the pretext of unwavering loyalty to an assumed “Indian tradition."

ANDAZ boasts a very strong score with ten songs, mainly sung by Dilip and Neena. In addition to the two mentioned earlier, memorable tunes include Dilip’s romantic Tu kahe agar (“If you but say…&rdquo![]() , his melancholy ode to Neena and Rajan’s wedding, Toote na dil toote na (“Don’t break, O my heart&rdquo

, his melancholy ode to Neena and Rajan’s wedding, Toote na dil toote na (“Don’t break, O my heart&rdquo![]() , and Neena’s mournful chronicling of Rajan’s gradual rejection of her in Uthaye ja unke sitam (“Take away his oppression&rdquo

, and Neena’s mournful chronicling of Rajan’s gradual rejection of her in Uthaye ja unke sitam (“Take away his oppression&rdquo![]() and Tor diya dil mera (“He has broken my heart&rdquo

and Tor diya dil mera (“He has broken my heart&rdquo![]() .

.

[The Gurpreet Video International (GVI) DVD release of ANDAZ offers a decent quality print of the film with good sound. Superior-quality subtitles accompany the dialog, but unfortunately none are included for the songs.]

BABUL

(“Father’s house&rdquo![]()

(1950, Hindi, 142 minutes)

Directed by S. U. Sunny

Story and dialogues: Azm Bazidpuri; Lyrics: Shakil Badayuni; Music: Naushad; Art direction: V. Jadhavrao; Director of photography: Fali Mistry

This operatic fable spotlights the early Dilip Kumar in a DEVDAS-like fable of an ill-fated poet-hero loved by two women, yet able to attain neither. Ashok (Kumar) comes to the idyllic Madhuban—a (literally) model village, often represented by an obvious tabletop mockup—to serve as its postmaster, a job that seems to require little beyond sending an occasional telegram. This leaves him plenty of time to lounge around his bungalow in natty suits, smoke cigarettes, paint, and compose soulful Persianate love songs—all markers of urbanity and (here) modernity.

He is loved from the first by Bela (Nargis), the simple but spirited daughter of the former postmaster, who prepares his meals, teases and amuses him, and dreams of longterm domestic bliss as his wife. Her hopes are nurtured by Ashok’s gift of gold jewelry (sold off by a poor neighbor) suitable for a bride, but then are dashed when he takes a shine to Usha (Munawar Sultana), the haughty daughter of the local Rajput zamindar (landowner), who inhabits a hilltop mansion done up in high Indo-deco style. Usha, who drives a big foreign car and sports an urbane wardrobe, seems more a match for the dashing young postmaster, and when she falls in love with his singing and arranges for him to give her music lessons (at a grand piano in a boudoir adorned with a statue of cupid and paintings of famous lovers of the past), the two seem headed for a lifelong duet.

But the heartbroken Bela intervenes, revealing to Usha her own (misguided) belief that Ashok has already professed his love for her; this causes Usha (in a surprising show of class-transcending compassion) to renounce her love for Ashok in favor of Bela’s prior claim, and to accept a pending proposal from the aristocratic son of one of her father’s cronies. As Usha’s wedding approaches, both she and Ashok lapse into depression, while Bela exults (despite recurring nightmares of a black-veiled rider coming to carry her away); a happy ending appears increasingly unlikely, and happily the director makes no last minute attempt to manufacture one.

There appears to be no moral to this story, apart from the fact that Fate can be Cruel (and urban boys should be careful about what they say to rural girls?). The many tropes present—the dispirited DEVDAS-type lover, the rivalry between two women who respectively suggest “tradition” and “modernity,” the sacrifice of personal happiness in order to maintain family honor, and a ludicrous and greedy munshi (the manager of the zamindar’s estate) and his family thrown in for comic relief—appear to be peripheral to the director’s main agenda, which is the evocation of romantic mood. Though the soundstage sets are sometimes hokily theatrical, the cinematographer achieves great things through atmospheric lighting, especially during night scenes, creating hauntingly beautiful effects suggestive of German expressionism (incidentally, Fali Mistry was the guru of V. K. Murthy, Guru Dutt’s brilliant cinematographer, and it shows). A score of fifteen musical numbers, mainly devoted to the joys and pains of love, makes this essentially a ghazal anthology in which brief dialogs serve largely to connect and frame each successive lyric. Especially notable are the thrice-refrained Chod babul ka ghar (“Now you must leave your father’s house&rdquo![]() , which evokes the vidai (leave taking) songs performed when a newly-married girl departs from her maternal home and village, the lovesong Nadi kinare (“On the bank of a river&rdquo

, which evokes the vidai (leave taking) songs performed when a newly-married girl departs from her maternal home and village, the lovesong Nadi kinare (“On the bank of a river&rdquo![]() performed by Ashok and Usha backed by a chorus of dramatically-picturized boatmen, and their mournful duet-in-separation Duniya badal gayee (“My world has changed&rdquo

performed by Ashok and Usha backed by a chorus of dramatically-picturized boatmen, and their mournful duet-in-separation Duniya badal gayee (“My world has changed&rdquo![]() .

.

Nargis is pleasing in an ingénue role, but Sultana’s character, though initially vain and shallow, proves to be the more complex, and she renders it effectively. Kumar, well enroute to earning his twin 1950s titles as “King of Tragedy” and “Darling of Millions,” delivers his usual stellar performance, exuding charm and sensuality while still managing to seem like the boyish Postman Next Door.

[The SKY Entertainment DVD of BABUL is of good quality and has decent subtitles for both dialog and songs. There are a few gaps where the print appears to have been broken, however.]

GUNGA JUMNA

1961, Hindi, 175 minutes

Directed by Nitin Bose

Screenplay: Dilip Kumar; Dialogues: Wajahat Mirza; Lyrics: Shakeel Badayuni; Music: Naushad; Cinematography: V. Baba Saheb

Despite its lush Technicolor tints, this big-budget film, scripted and produced by its star, Dilip Kumar, is a rural tragedy that presents a darker variation on some of the themes featured in Mehboob Khan’s classic, MOTHER INDIA (1957): the poignancy of two brothers on opposite sides of the law, the lingering grip of feudal oppression in rural India after Independence, and the struggle to reconcile family loyalty and personal justice and revenge with the implacable law codes of the modern state. By focusing its story and its audience’s sympathies on the brother who goes astray, however, the film invites a critical and pessimistic appraisal of the state’s ability to protect the underprivileged, and its tragic central character thus anticipates the “angry” proletarian heroes popularized by Amitabh Bachchan in the 1970s (e.g., the latter’s influential DEEWAR, 1975).

The boys Gunga and Jumna, named for the two great holy rivers of north India, are the sons of poor widowed Govindji (Leela Chitnis), who slaves away in the mansion of the local zamindar or feudal landlord, assisted by Gunga, the elder son. Bright-eyed Jumna is sent to the village school, where he imbibes inspirational lectures about the New India, in which citizens shoulder civic responsibilities and enjoy wonderful opportunities, in the form of the song Insaaf ki dagar (“the path of justice&rdquo![]() . Ironically (and this is typical of the film), close-up shots of the smiling, singing schoolmaster and children praising the New Order are juxtaposed with pathetic images of Govindji and Gunga laboring painfully under the Old; clearly, the democratic dispensation has not reached everyone (and in fact, reading between the lines, it is the continuing exploitation of the poor that makes middle-class mobility possible). To make matters worse, the zamindar’s wastrel brother-in-law, Hariram Babu (Anwar Hussain), steals his own sister’s jewelry while she is bathing, discarding its gaudy box on a dung heap where it is found by Gunga. It turns up when police, alerted by the shrewish sister, search the boys’ home, and Govindji is arrested, a disgrace that proves too much for her.

. Ironically (and this is typical of the film), close-up shots of the smiling, singing schoolmaster and children praising the New Order are juxtaposed with pathetic images of Govindji and Gunga laboring painfully under the Old; clearly, the democratic dispensation has not reached everyone (and in fact, reading between the lines, it is the continuing exploitation of the poor that makes middle-class mobility possible). To make matters worse, the zamindar’s wastrel brother-in-law, Hariram Babu (Anwar Hussain), steals his own sister’s jewelry while she is bathing, discarding its gaudy box on a dung heap where it is found by Gunga. It turns up when police, alerted by the shrewish sister, search the boys’ home, and Govindji is arrested, a disgrace that proves too much for her.

The orphaned boys grow up, with Gunga (Dilip Kumar) now working hard for the fast-talking Kallu Lala, the Munim or village accountant (Kanhaiyalal, playing a comic mercantile-caste role, similar to the avaricious Sukhilala he portrayed in MOTHER INDIA), and continuing to finance the education of Jumna (Nasir Khan, Kumar’s actual brother; the more popular actor had assumed a Hindu name in the troubled aftermath of Partition. Regrettably, both men look about a decade too old for the roles they are playing.) Though he now studies in the city (coming and going by the inevitable railway), Jumna still loves his primary school sweetheart, the zamindar’s daughter Kamla. Yet when, against her wishes, she is betrothed to another, Jumna refuses to intervene, since he is still unable to support her in a manner befitting her social status. The pathetic scene in which Kamla, during a stormy night, comes to beg him to elope with her, establishes Jumna as a disciplined but inhuman paragon of social propriety — an object of simultaneous admiration and disapproval — and sets the stage for the eventual showdown between the two brothers. In contrast, the earthy but self-confident Gunga talks back to the zamindar and to everyone else, especially to low-caste village belle Dhanno (Vyjayanthimala), with whom he has a long-term teasing relationship that blossoms into love when he saves her from being molested by Hariram. The latter has now assumed control of the estate on the old zamindar’s death, and seeks revenge on Gunga by framing him on a charge of theft, sending him to prison, and eventually driving him out of the village and into the hills, where he joins a band of dacoits. Dhanno, who knows his innocence, follows him into exile and they are eventually married by the kidnapped village priest. Meanwhile, in the city, when the fraternal stipends stop coming in the mail, Jumna nearly starves until he is befriended by an idealistic policeman who convinces him to join the force. His first posting, naturally, will be to his hometown of Haripur to stamp out a notorious band of dacoits…..

On the long road to tragedy there are plenty of diversions. Linguistic coding is artfully used, with Gunga and Dhanno’s raucous arguments in colorful Bhojpuri dialect contrasted with Jumna’s carefully-measured pronouncements in Khari Boli or “high” Delhi speech. Rural life is also celebrated in exhuberant songs and dances (Naino ki dor, Aja ghar aja) and in a wonderful scene of a kabbadi tournament — a rowdy village game somewhat resembling American football. The sweeping landscape of the Deccan, with its arid mesas and lush green valleys forms a gorgeous backdrop to many scenes. Its sun-dappled sweep effectively counterpoints the dark ironies of Kumar’s ultimate vision: that the impartial “justice” of the modern state may triumph at the expense of those most in need of its protection.

The DVD of GUNGA JUMNA issued by Digital Entertainment Incorporated (DEI) is of good quality; songs are unsubtitled.

[For a sensitive analysis of this film and of the career of its producer and star, see Ziauddin Sardar’s essay, “Dilip Kumar Made Me Do It,” in Ashis Nandy (editor), The Secret Politics of Our Desires (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1998), pp. 19-91. The film is discussed on pp. 40-45 of the essay.]

MADHUMATI

(1958, Hindi, B&W, 154 minutes)

Directed by Bimal Roy

Screenplay: Ritwik Ghatak; Dialogues: Rajinder Singh Bedi; Music: Salil Chowdhury; Lyrics: Shailendra; Director of Photography: Dilip Gupta

Bimal Roy’s most successful film and ostensibly his most blatant concession to mass tastes, MADHUMATI is an overdetermined but compelling mystery-romance involving reincarnation and a haunted mansion, set in the Himalayan foothills and ornamented with lovely (and famous) songs. It boasts a screenplay by famed Bengali director Ritwik Ghatak, and dialogues by Urdu novelist Rajinder Singh Bedi. The film begins, as they say, on a dark and stormy night, as Devendra (Dilip Kumar) and a companion are enroute through the rain-lashed mountains to meet a train carrying Devendra’s wife and child. When a landslide blocks the road, the two men take shelter in a ruined mansion, which Devendra finds unaccountably familiar – he knows his way around, and recognizes a portrait of the mansion’s former owner, Raja Ugranarayan, as his “own” handiwork. Soon he begins a long flashback to a previous life, in which he came here one sunny day as the young clerk and amateur artist Anand, to supervise the timber estates of the arrogant and cruel Ugranarayan (Pran). In his establishing song, Anand exults in the beauty of the mountain landscape and reveals his poetic temperament (Suhaana safar aur yeh mausam haseen, “a pleasant journey and this beautiful season&rdquo![]() . Defying the Raja by venturing into a forbidden tract of forest, Anand falls in love with the vivacious and uninhibited Madhumati (Vyjayanthimala), the daughter of a local chieftain whose son was earlier murdered by the Raja’s henchmen. Anand’s own egalitarian progressivism, coupled with his sympathy for Madhumati and her family, soon sets him on a collision course with the Raja, who takes revenge through a malevolent scheme.

. Defying the Raja by venturing into a forbidden tract of forest, Anand falls in love with the vivacious and uninhibited Madhumati (Vyjayanthimala), the daughter of a local chieftain whose son was earlier murdered by the Raja’s henchmen. Anand’s own egalitarian progressivism, coupled with his sympathy for Madhumati and her family, soon sets him on a collision course with the Raja, who takes revenge through a malevolent scheme.

The story, punctuated by plenty of dark cloudbursts, sustains its suspense through complications that include a flashback within the flashback, a trainwreck in the frame story, and no less than three different embodiments of the heroine. Comedy is provided by Anand’s drunken servant Charan Das (Johny Walker), and Roy’s social-realist eye is apparent even in this fantastic setting, capturing plausible portraits of some of the laborers on the Raja’s estates. The film has affinities with Hitchcock’s REBECCA (1940) and VERTIGO (1958), and the initial meeting of hero and heroine closely resembles that of Raj Kapoor’s later RAM TERI GANGA MAILI (1984), wherein (as here), woman stands in for nature and unspoiled folk tradition and the villain for exploitative (capitalist) culture, with the hero as intermediary. The film’s eight songs include the haunting hit Aaja re pardesi (“Come, O stranger&rdquo![]() , by which Madhumati first summons Devendra. Kumar gives an appropriately haunted performance as the two incarnations of Devendra/Anand, and Vyjayanthimala is alternately earthy and ethereal in the various permutations of the title character.

, by which Madhumati first summons Devendra. Kumar gives an appropriately haunted performance as the two incarnations of Devendra/Anand, and Vyjayanthimala is alternately earthy and ethereal in the various permutations of the title character.

[The Yash Raj Films DVD of Madhumati includes subtitling for the songs, and offers a viewable but less-than-ideal print of the film. That better copies survive is apparent from one of its bonus features – a portion of a documentary about Bimal Roy by Nasreen Munni Kabir, which includes crisper and less-scratched footage from the film.]

MUGHAL-E-AZAM ("The Great Mughal")

1960, Hindi, 198 minutes.

Produced and Directed by K. Asif

Cinematography: R. D. Mathur; Dialogs: Aman, Kamal Amrohi, Ehsan Rizvi, Wajahat Mirza; Music: Naushad; Lyrics: Shakeel Badaiyuni; Dance Director: Lachchu Maharaj

The theme of the conflict between passionate individual love (pyar, mohabbat) and duty—especially the duty owed to one's father and patriarchal family lineage (involving the obligation to maintain izzat or "honor," maryada, "propriety," and usool, "principles") may be to mainstream Hindi filmmaking what "boy meets girl" was to Samuel Goldwyn's Hollywood—an abiding preoccupation that spawns endless cinematic permutations. Yet for sheer baroque grandiosity, K. Asif's excessive elaboration of the theme remains in a class by itself, and more than forty years after its release, still holds a place on nearly every list of the "ten best Hindi films of all time." Purportedly a decade in the making, it was said to have been the costliest film yet produced in India. It's not hard to see why. Asif's grand operatic vision piles spectacle on spectacle, moving masses of extras with a choreography reminiscent of Fritz Lang or Sergei Eisenstein, and fabricating fairtytale sets that have definitively stamped popular imaginings of Mughal imperial opulence. Asif's ultimate trump card was technicolor—then prohibitively expensive for Indian filmmakers, and so reserved by the director for two legendary climactic musical scenes, both set in the royal pleasure pavilion or Shish Mahal ("palace of mirrors," stunningly crafted by mirrorwork master Agha Shirazi), that unfold as mind-blowing epiphanies.

The simple storyline blends facts of history—the sometimes tumultuous relationship between the Mughal empire's most charismatic ruler, Akbar the Great (1542-1605), and his eldest son and designated heir Prince Salim (later the Emperor Jahangir, 1569-1627), a far weaker character with a well-attested taste for wine, women, and opium—with the popular story of the slave girl and court dancer Anarkali ("pomegranate blossom"), for whose sake Salim is supposed to have defied his father, and whose legendary fate was to be walled-up alive at Akbar's order. In the role of Akbar, Prithviraj Kapoor gives his quintessential performance as outwardly-stern-but-inwardly-suffering patriarch (cf. Judge Raghunath in AWARA), declaiming every line (composed in an Urdu so thickly Persianized one could weave rugs out of it) in a stentorian baritone that even Amitabh Bachchan might envy. As the film opens, Akbar, long childless despite his ample harem (containing many Hindu princesses acquired through marital alliances with feudatory Rajput kingdoms), petitions the Sufi saint Salim Chishti for a son; the murmured prayers of the "friend of God" fade into rejoicing in the palace over the birth of an heir, named for the saint, to Joda Bai (Durga Khote), Akbar's principal queen. But the young prince, reared amidst bevies of doting slave girls (with a cameo by Johnny Walker as a transvestite eunuch) soon proves to be anything but saintly. When Akbar finds him collapsed in a drunken stupor, he packs the lad off to the front lines of the ever-expanding Empire, under the care of trusted general Man Singh, for a little toughening up—fourteen years worth. War works wonders; the chastened, grown-up Salim (Dilip Kumar) becomes a military hero, sending home versified reports penned in his own blood. Eventually, even Akbar is satisfied and calls him back. The matronly Joda Bai, who has been fervently praying to Lord Krishna for her son's return, gives Salim a maternal welcome that stops just short of suckling him. Salim soon dons bejeweled slippers and, with apparently equal ease, slips back into the sybaritic lifestyle of the court. Enter Bahar ("springtime," Nigar Sultana), an ambitious lady-in-waiting who aspires to the rank of empress (a possible allusion to the ruthless Persian princess Nur Jahan, who would eventually dominate the historical Jahangir's life). Seeking to ingratiate herself with Salim, she hires a moody sculptor (Kumar) to create a statue embodying eros. He takes as his model a palace slave-girl, Nadira (Madhubala), whose impersonation of the still-uncompleted statue steals Salim's heart. It charms the emperor as well, who renames her "Anarkali" and promotes her to the queen mother's service. Anarkali likewise falls in love with Salim and the latter soon vows to make her his future Empress, against her own and his father's wishes. The rest of the film (and there is plenty more!) milks this scenario—two strong-willed males battling over honor and authority, with one beautiful woman as the stake and another as scheming nemesis—for every conceivable drop of blood and pathos.

There is eroticism aplenty, albeit often veiled and fetishistic: as when Anarkali (twice) writhes in chains in Akbar's darkest dungeon under the gaze of black-clad guards, or the moonlit lovescene in which Salim slowly fondles her ecstatic face with an ostrich feather. There are splendid musical numbers, including a poetic duel over the nature of love by two female choruses, stunning kathak dances set in the Shish Mahal, Anarkali's immortal song of defiance of the Emperor, Pyaar kiya to darna kya? ("If you've fallen in love, what is there to fear?"), and the rousing Zindabaad ("Long live love!"), sung by the sculptor and a massed male chorus as Salim is prepared for (apparent) execution for defying his father. There is a colossal battle scene that set a new standard in military spectacle and pyrotechnic effects. There are dazzling operatic sets (erected on sometimes all-too-evident soundstages) that evoke less the rugged architecture left by Akbar (e.g., at Fatehpur Sikri) than the infinite geometries and aquatic fantasies of the more decadent emperors who succeeded him, especially Jahangir's son Shah Jahan, creator of the Taj Mahal. And there is the Artist, embodied in the nameless sculptor clad in a monk-like robe and credited with a series of realistic 3/4 bas reliefs that resemble nothing in historical Mughal art, but suggest the humanism and romanticism that he (and the filmmaker) champions. Their creator is portrayed as a fearless solitary genius, beholden to his royal patrons, yet not afraid to confront them with unpleasant Truth (e.g., in a frieze of a political execution), though the principal outlet for individual expression and dissent in his world remains passionate Love. This is embodied in Anarkali herself, who literally brings to life his plastic vision and whose incandescent portrayal by Madhubala upstages both of the bombastic male leads.

And finally, there is—and not at all subtly—politics. Here the film addresses several agendas. Akbar's reign has sometimes been viewed (especially by British historians) as the highwater mark of Hindu-Muslim amity and state-level collaboration, but the liberal-minded emperor has also been castigated by Hindu nationalists as a wolf in sheep's clothing, who abolished the jizya and pilgrimage taxes in order to weaken Hindu resistance, and who co-opted Rajputs into his service even as he drew their daughters into his overpopulated harem. As a Muslim director negotiating the tricky communal terrain of post-Partition Bombay, Asif is clearly concerned to re-establish Akbar as an exemplary secular nationalist. Much is made of his participation in Hindu rituals with Joda Bai and his close reliance on Rajput ministers (all well attested in the annals of the period), but the director's principal means to his end is to transpose the family onto the nation, with Akbar-the-wounded-patriarch portrayed as a suffering Father India, whose every speech suggests his willingness to sacrifice his personal desires and even his own son for "the people of Hindustan." The Nation looms large throughout, and literally so in the opening and closing segments, when viewers are addressed by an enormous relief map that announces (in a male voice), "I am Hindustan," and proclaims Akbar to have been one of his greatest devotees.

Yet despite the equally portentous presence in several scenes of a giant scale of justice, the audience surely realizes that the decrees of absolutist authority—in the nation as in the family—are not always just. Thus Akbar's unrelenting persecution of Anarkali—his constant denigration of her as a social-climbing slut, for example—contradicts what the audience knows about her purity of heart and lack of ambition. So Salim gets to deliver resounding speeches decrying him as a tyrant and oppressor—though here the context appears squarely and safely personal and domestic: a son's righteous railing at a father's tyranny over his heart and his matrimonial options. Given Asif's agendas, as well as the fact that history records that Salim did not marry someone named Anarkali and preserves the popular legend of her execution, the filmmaker must ultimately give victory to the Father, even bringing the effusive Mother on board for good measure—though he manages a face-saving final twist to leave viewers with a taste of what might be called Compassionate Paternalism. In 1960, this may still have been what many Indians saw the State as potentially providing. But their other parting image is of Anarkali's devastated face—a reminder, perhaps, of the price that is inevitably paid, by some, for the preservation of patriarchal usool.

RAM AUR SHYAM

(“Ram and Shyam&rdquo![]()

Hindi, 1967, 165 minutes

Produced by B. Nagi Reddi

Directed by Chanakya

Story and screenplay: D. V. Narasaraju; Dialogs: Kaushal Bharati; Music: Naushad; Lyrics: Shakeel Badayuni; Cinematography: Marcus Bartley; Art Director: S. Krishna Rao

This delightful romp through Hindi film conventions (executed with especially baroque flair by a Madras studio, Vijaya International), features Dilip Kumar, near the end of his primary-hero career, apparently enjoying himself hugely in what the credits proudly trumpet as “HIS FIRST DUAL ROLE.” (Indeed, the double is such a staple of Indian cinema that it seems inevitable that every leading man will play one sooner or later.) Here he is both Ram, the timid and seemingly mentally-retarded son of a millionaire industrialist, and Shyam, a sturdy yeoman brawler with an appetite like that of the legendary Bhima of the Mahabharata. Mythological jokes and allusions (playing on the rhyming Rama-Krishna names) abound, especially in the song lyrics. It soon turns out that Ram isn’t really retarded, just terrorized by his sadistic, whip-wielding brother-in-law, Gajendra (Pran, of course), who, goaded by an evil mother, keeps Ram, along with his own wife and daughter, virtual prisoners in their palatial mansion. But when Gajendra contrives to get Ram engaged to Anjana (Waheeda Rehman, here graciously enduring the sixties—not even a beehive hairdo can mar her beauty and self-confidence!), the only daughter of another wealthy businessman (in order to snatch her huge dowry, after which he plans to do away with Ram), the trembling, stuttering heir escapes. As it happens, his burly look-alike Shyam is also in town that day, and circumstances contrive (a key term for this film) to get each mistaken for the other without their knowledge. They quickly fall into roles (and love affairs) they will maintain for most of the film—with Ram, after a brief and hilarious stint as a sadhu, finding happiness in the countryside and getting thick with Shyam’s childhood sweetheart Shanta (Mumtaz), and Shyam taking charge of the family business, romancing Anjana, and putting Gajendra in his place. The plot thickens when the villain figures out what is going on and contrives a diabolical scheme to do away with both men. Nobody in the film seems to take the story very seriously, least of all Kumar, who (despite looking a bit winded during rooftop chases) clowns his way through both roles with a zest that prefigures the antics of Shah Rukh in the 90s. Add lurid technicolor sets (Anjana’s Barbie-moderne home, and Gajendra’s gothic and rococo mansion), bouncy songs (especially the children’s birthday party number, Aayee hai bahaaren, in which Shyam sings, “Ram’s lila delights the heart, Krishna is playing his flute!” while tiny tots do the twist), and some fine camerawork (Chanakya, who previously directed successful Telugu and Tamil versions of this story, has a sharp eye for locations and their possibilities), and you have a double-your-pleasure package.

[The Baba Traders DVD of this film is of uneven quality. Images become blurred during action sequences, some subtitles are missing, and songs are unsubtitled.]

SUNGHURSH

(a.k.a. SANGHARSH, “Struggle,” 1968, Hindi, 158 minutes)

Produced and directed by H. S. Rawail

Based on a Bengali novel by Mahashweta Devi; screenplay: Anjana Rawail; dialogs: Gulzar, Abrar Alvi; choreography: Gopi Krishna; lyrics: Shakeel Badayuni; music: Naushad; playback singers: Lata Mangeshkar, Mohammed Rafi, Asha Bhonsle; art direction: Sudhendu Ray; costumes: Anjana Rawail; cinematography: R. D. Mathur

This beautiful and unusual film, displaying great technical accomplishment and exceptional performances, deserves to be better known (the Encyclopaedia of Indian Cinema gives it a curt, dismissive paragraph under the spelling SANGHARSH). Belonging to the uncommon genre of “historical” and containing substantial religious subject matter, it is additionally uncommon in that it tells the story of no known figure of history or legend. Instead it uses mid-nineteenth-century Banaras—a.k.a. Kashi/Varanasi, north India’s great Hindu pilgrimage center—as the backdrop for a complex tale involving such thematic staples as a multi-generational family feud, conflict between love and duty (centering on a “fallen woman&rdquo![]() , and the glories of self sacrifice for the sake of dosti (male friendship), but also introducing the tension between the ritual violence of Shakta religion (requiring periodic blood sacrifice to a powerful mother goddess), and a nonviolent religious path of love and compassion. The film implicitly subscribes to the upper-middle class critique of the former and endorsement of the latter that is in part a legacy of colonial discourse, though it complicates this picture somewhat through its allegiance to family tradition (apparently, even a serial murderer has to be tolerated if he’s your grandpa). However, its ultimate concern to reunite two sundered brothers (actually, as in the Mahabharata, first cousins, and played by a Muslim and a Hindu actor) suggests a subtext that isn’t really about Hinduism at all, but about the communal divide that haunts post-Partition India, here projected into the past and disguised within an exclusively Hindu milieu.

, and the glories of self sacrifice for the sake of dosti (male friendship), but also introducing the tension between the ritual violence of Shakta religion (requiring periodic blood sacrifice to a powerful mother goddess), and a nonviolent religious path of love and compassion. The film implicitly subscribes to the upper-middle class critique of the former and endorsement of the latter that is in part a legacy of colonial discourse, though it complicates this picture somewhat through its allegiance to family tradition (apparently, even a serial murderer has to be tolerated if he’s your grandpa). However, its ultimate concern to reunite two sundered brothers (actually, as in the Mahabharata, first cousins, and played by a Muslim and a Hindu actor) suggests a subtext that isn’t really about Hinduism at all, but about the communal divide that haunts post-Partition India, here projected into the past and disguised within an exclusively Hindu milieu.

After a credit sequence that breaks the Bombay norm by using Devanagari rather than Roman letters (further underscoring the Indianness of the story), the film opens with the boy Kundan (Dilip Dhavan) being raised by his grandfather, the powerful Shakta priest and Big Man of Kashi, Bhavani Prasad (Jayant). A devotee of the black goddess Kali, Bhavani Prasad longs to initiate Kundan as his successor and head of a prestigious temple and pilgrim guesthouse (dharmshala) on the bank of the Ganga. There’s only one hitch: Bhavani Prasad traces his lineage to the “thugs”—thieves who ritually murdered travelers as sacrifices to Kali, a practice ostensibly stamped out at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Yet when particularly wealthy pilgrims find their way to his guesthouse, Bhavani Prasad reverts to the Old Time Religion. Kundan is repulsed by this, as were his parents (from whom his grandfather has cruelly separated him) yet he lacks the strength to oppose Bhavani Prasad. (The question of calling the police doesn’t even arise.) To make matters worse, Kundan is soon separated from his childhood playmate and sweetheart Munni (Rano), an orphan who loves to dance. She is “adopted” one day by a wealthy matron from Calcutta who looks kind, but one suspects (as they say) that there’s “something black in the dal….” Meanwhile, when Kundan’s father announces that he is taking the boy away from Bhavani Prasad, he mysteriously disappears and only his bloodstained shawl is found. Bhavani Prasad tries to pin the blame for the crime on his archenemy and nephew, Naubatlal, who has sworn to take revenge on Bhavani Prasad for the earlier killing of his own father, Bhavani Prasad’s brother. But before Naubatlal can do so, he too is cut down. Despite their mother’s pleas to let the cycle of vendetta cease, Naubatlal’s two young sons, Dwarka and Ganesh Prasad, now swear to avenge their father’s death. They grow up fast (turning into Sanjeev Kumar and Balraj Sahni) and move to Calcutta where they prosper as merchants, but continue to thirst for Bhavani Prasad’s blood—and that of his young protégé, Kundan.

All this is just for openers. The adult Kundan (Dilip Kumar—a bit old for the role, but his consummate acting soon makes one forget this), whose mother and sister have long ago fled to his maternal uncle’s village, continues to patiently serve his tyrannical grandpa in the Banaras temple, though he steadfastly resists taking “initiation” (which would involve committing ritual murder) and regularly preaches to the old man about a kinder, gentler dharma. Still, he has learned effective self defense against the regular assassination attempts mounted by his far off cousins. Then one day he meets a beautiful woman (Vyjayantimala) on the steps of the temple; though she appears to be a simple pilgrim, she is in fact a legendary courtesan named Laila, who has come from Calcutta after her madam’s death. She is also, of course, Munni, but although Kundan doesn’t know of either identity, he is sufficiently attracted to her to sing a lovesong in a misty, moonlit garden (Jab dil se dil takrata hai, “When two hearts collide”—the first of six fine Shakeel-Naushad songs).

Enter comic interest in the form of Kundan’s fast-talking mama or maternal uncle, who invites Kundan to his sister’s wedding back in the village. Grandpa isn’t invited, which is fine with Kundan, since this means he can really cut loose (his charming song and dance while ostensibly stoned on bhang, Mere pairon mein ghungharoo bandha de, “Tie bells on my ankles,” seems a precursor to Bachchan’s similar number in DON). That his Calcutta cousin Dwarka shows up is fine with Kundan too, and he doesn’t even mind a few more assassination attempts, especially when the mysterious beauty from the garden reappears as well. She now reveals that she is his long lost Munni—but not that she is also the “fallen” Laila, who has been hired by the Calcutta cousins to seduce him and bring him back to them (though in fact she has taken the job only in order to protect Kundan). Kundan is overjoyed and is on the point of proposing marriage when Bhavani Prasad turns up and denounces Munni/Laila as a ***** who is in league with their enemies. Because she is unable to refute these accusations, Kundan believes them and renounces Munni/Laila. Meanwhile Dwarka’s elder brother, Ganesh Prasad, falls in love with her too. (Who wouldn’t? Vyjayantimala is at her best here, in songs like the coquettish Agar yeh husn mera, “If I unleash my beauty,” and the imploring Mere pas aao, nazar to milao, “Come to me, return my gaze.&rdquo![]()

When the cruel Bhavani Prasad finally goes home to Mother (apparently unrepentant for his crimes), Kundan decides to end the feud once and for all, but his attempt to reason with Dwarka goes disastrously awry. He then resolves to go to Calcutta where, since his elder cousin has never seen him as an adult, he tries to atone for his grandfather’s sins by assuming the identity of the manservant Bajrangi (an epithet of Hanuman, Ram’s faithful monkey) and humbly waiting on Ganesh Prasad. But this effort too is threatened, both by the appearance of faithful old retainers of the two clans (who know his identity) as well as by Ganesh Prasad’s plan to take a second wife—the lovely and heartbroken Laila.

Perhaps because both the story and the screenplay are by women, the film displays an unusual sensitivity to the sufferings imposed on women by men’s obsession with honor and revenge. And although Laila shows some remorse over her years of residence in a kotha (a high class brothel), she remains spirited and assertive, convinced that she is deserving of Kundan’s love. As the one man who tries to break the cycle of violence by assuming a pacifist, Gandhian role, Dilip Kumar delivers a performance of extraordinary range, restraint, and conviction. Everything else about the production shows similar quality, reflecting the work of some of the best artists of the period (e.g., dialogs by talented directors Gulzar and Abrar Alvi; choreography by Gopi Krishna of JHANAK JHANAK PAYAL BAAJE fame). Though a few scenes are shot in Banaras and environs, most of the outdoor locations utilize a Deccan pilgrimage site closer to Bombay (recognizable by architectural details and the dark stone typical of Maharashtra), but with similar temples and ghats. The numerous soundstage sets are unusually sumptuous and atmospheric and show a rare degree of attention to detail (e.g., Bengali style architectural motifs for a temple garden scene that is supposed to transpire in Calcutta).

[This film is a gorgeous treat, and the SKY Entertainment DVD is worthy of the occasion. Images are crisp, colors rich, and optional subtitles are provided for songs as well as dialog.]

Wednesday, 29 February 2012

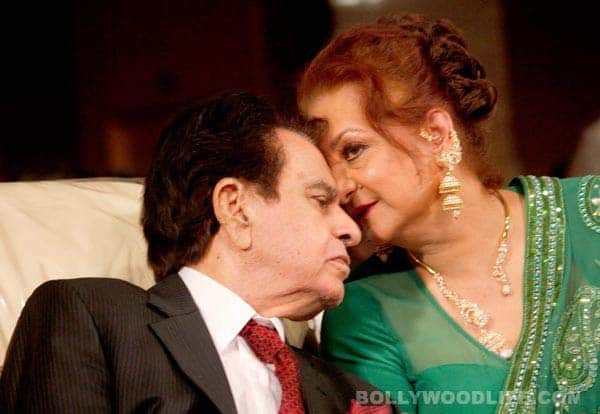

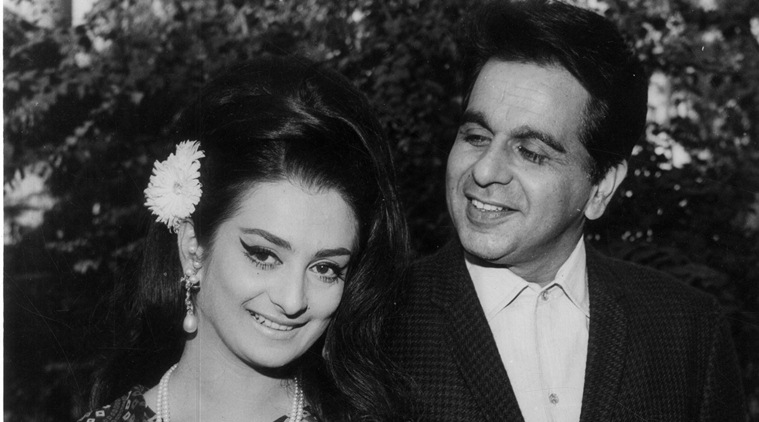

The gorgeous Saira Banu, who entered the industry at the age of 17, was a woman who followed her heart. As a teenager, she had no qualms about pursuing Rajendra Kumar despite him being a married man with kids. Their torrid affair fizzled out but she once again shocked the industry when she married superstar Dilip Kumar who was 22 years her senior...

TEENAGE LOVE AFFAIR How Rajendra Kumar Stole Her Heart

Saira Banu shot to instant fame when she debuted opposite Shammi Kapoor in Junglee. Her stunning beauty and innocent charm got her many film offers and in no time, she was working with the leading actors of the era. One such actor was Rajendra 'Jubilee' Kumar who was on a high with several hits to his credit. Saira and Rajendra were one of the most sought-after couples of the 60s and starred in box office successes like Ai Milan Ki Bela (1964), Jhuk Gaya Asman (1968) and Aman (1967). The attraction was inevitable and rumours of their secret affair made the gossip rounds with a vengeance. Rajendra was a married man with kids so this love affair was doomed from the beginning but his marital status didn't seem to matter to Saira who was keen on settling down with him. The actor was also quite taken with the petite beauty and planned to propose to her. However, it was here that Saira's domineering mother Naseem Banu stepped in. Unhappy with her daughter's liaison with a married man of a different faith, she decided to take matters in her own hands.

A NIGHT THAT CHANGED SAIRA'S LIFE Dilip Proposes Marriage

Like millions of girls across the country, Saira had nursed a crush on Dilip Kumar since she was 12 years old. Naseem decided to exploit her attraction to the superstar and contacted Dilip. Her diligence and pleading paid off; Dilip, who had worked with Naseem in the past and shared a good rapport with her, agreed to marry Saira. Interestingly, Saira herself found the idea fascinating – after all she was getting hitched to the man of her dreams. Rajendra Kumar, with whom she had broken off some time back, was soon forgotten!

People predicted the marriage wouldn't last, primarily due to the 22-year age gap, but the couple seemed very compatible and even starred in films together.

When I first heard that Dilip Kumar’s autobiography was being released, I was puzzled given media reports that he has been suffering from Alzheimer’s for some time now. Surely it was a biography and not an autobiography? Something amiss here, that’s what I thought.

Being an ardent fan of old Hindi movies, I nevertheless bought the book in spite of doubts over its authencity. And I am glad I did!

Right through my school years, like most kids are wont to do, I went for the more light hearted, and what I then thought, better looking heroes. Shammi Kapoor was my first (and lasting) love, followed by Dev Anand and Rajesh Khanna. Dilip Kumar held no appeal for me. I neither thought he was good looking nor as great an actor as the adults in my family did.

All that changed as I matured and developed a finer appreciation for good cinema and acting. It was then that I understood why Dilip Kumar was hailed as the thespian of Indian cinema. And when I finally saw Ganga Jamuna, sometime in the late 1990s on the recommendation of a friend, the realization of just how talented he was really came home.

The stronger the substance, the longer the shadow

In his autobiography, as narrated to Udayatara Nayar, Dilip Kumar attempts to separate the star from Yousuf Khan, the person he maintains he really is.

Reading the book, the feeling grew on me that the title can be interpreted as the long shadow of Dilip Kumar determinedly dogging Yousuf Khan’s heels all his life, growing in stature till it threw a cast over the real substance of the person he really was. Sadly, in the eyes of not just his fans, but his industry colleagues and even his family (with the sole exception of perhaps his wife).

Another way of looking at it is The Substance and the Shadow is an attempt by Dilip Kumar, in his twilight years, to finally set the record straight on many misconceptions and myths that he may have felt dogged by, much like a faithful shadow that never leaves you. In fact, he says as much at the start of his narration. That may have been the intention with which he narrated his life but at the end of it, he succeeds in leaving the reader thoughtful and pensive over the many layers in this enigmatic man, revealed a chapter at a time. Much like the layers he managed to embed in his screenplays and roles.

A Life Review

This is perhaps one of the areas where the book triumphs. It truly is a narration of a life rich with emotion and experience, and reading it is akin to Dilip Kumar sitting across and talking to the reader, mesmerizing her or him just like he did with his characterization and dialogue delivery in his various films.

The narration, much like the man he reveals himself to be, is a meticulous chronicling of his life from his childhood in Peshawar. As meticulous as the method he used in selecting, preparing and executing the roles he played in the 60 odd films he starred in over the course of a career spanning some 4 odd decades.

Neither does Dilip Kumar (habit will have us, mere strangers to him, calling him that) shy away from talking about the controversies in his life, be it Madhubala or his second marriage. But, he does so like the gentleman he has always been, consciously shielding his wife from pain and the eyes of an ever critical and judgmental world.

“Kaun Kambhat bardasht karne ke liye pita hai; mein tho pita hoon ke bas saas le sakhoo.” This unforgettable dialogue from Devdas rings in your ears as you finish the last page of his rendering of his life. And you wonder if he had to tell the world his version of his life story in order to breathe more freely by finally uncorking the feelings he had bottled up over so many years.

If the book has any weak points, it is that the narration tends to fall flat here and there. There was also no need, I feel, for the section at the back featuring the reminiscences from industry colleagues and a few family members. That section rings completely false and tends to read like carefully worded press releases. No substance. None at all, I’m afraid.

Review Prompt

A screen or theatre actor is often given a prompt to cue an action or entry. What was the prompt for a hobbyist writer and blogger like me to write a review on Dilip Kumar’s autobiography?

I sometimes watch the broadcast of the now too many and overdone film awards. In one such broadcast, I was touched by the way Dilip Kumar turned to his wife, Saira Banu, with a helpless and childlike expression. The camera, they say, never lies. And on this one occasion, the camera revealed the bond and commitment that existed between this couple. During the same broadcast (I think several cine stars of yesteryear were being felicitated), I saw the emotion and pain on Waheeda Rehman’s face as she watched Dilip Kumar struggle to get up, leaning physically and emotionally on his wife.

I guess it is that memory that had me wondering how this autobiography could be written. Unless it was recorded when he was more healthy and being released only now.

I also wondered, just like I did when I read Conversations with Waheeda Rehman, if these stars who once shined so brightly were in financial need now? What else could be the reason for these two intensely private people to agree to talk about their lives?

Of course, like most ordinary mortals, it could be that they are going through a life review and wished to set the record straight before the curtain finally falls on their lives. But, if the books on their lives have been motivated by the need for money, I would request fans everywhere to go out and buy their books. It’s the least we can do for two stars who delighted us and gave us so much to dream about down the years. And that too stars who led their lives with much dignity.

It is one of the most enduring marriages in Bollywood but Dilip Kumar reveals that though aware of her ‘crush’ on him, he annoyed Saira Banu by refusing to work with her in films as he thought she was too young to pair with him on screen. The heroine, who fell in love with Kumar after watching his 1952 film Aan, finally married the man of her dreams in 1966 when he was in his early 40s while she was 22.

In his autobiography Dilip Kumar: The Substance And The Shadow, narrated by Udayatara Nayar, the screen icon, born in Peshawar (Pakistan) on 11 December 1922 and whose real name is Muhammed Yousuf Khan, reveals details about his courtship with Saira. “Ram Aur Shyam was very special for me in a personal way because I married Saira when the production of the film was nearing completion… Until then I was reluctant to even work with her for some reasons,” Kumar, 91, says in the book.

Saira, on her part, had already found a teacher to learn Urdu and Persian to impress Kumar. She had also got to know about his likes and dislikes. The actor was “pleasantly amused and delighted” but never gave any importance to “this crush directed at me”. As a family well-wisher, he also advised Saira’s mother to not let her work in films. She made her debut with 1961 hit Junglee opposite Shammi Kapoor. Saira had already worked with Kumar’s contemporaries Raj Kapoor and Dev Anand but working with the actor was still a distant dream.

In fact, director Nag Reddy wanted to cast Saira in Ram Aur Shyam but Kumar stopped him from doing that. The role finally went to Mumtaz, who he thought was more suitable for the part, making Saira very angry. Kumar vividly recalls the day he fell in love with Saira during a party thrown to celebrate her birthday and the house warming of their new banglow. ”When I alighted from my car and entered the beautiful garden that leads to the house, I can still recall my eyes falling on Saira standing in the foyer of her new house looking breathtakingly beautiful in a brocade sari. I was taken aback, because she was no longer the young girl I consciously avoided working with because I thought she would look too young to be my heroine. She had indeed grown to full womanhood and was in reality more beautiful than I thought she was. I simply stepped forward and shook her hand and for us Time stood still. For once, she let go of her annoyance with me and looked straight into my eyes and it did not take more than an instant for me to realize that she was the one Destiny had been knowingly reserving as my real-life partner while I was refusing to pair with her on screen!,” Kumar recalls. Kumar proposed to Saira while she was shooting for Jhuk Gaya Aasmaan. Their date, however, was interrupted by a phone calls from a “lady friend with whom I had broken off a relationship months ago”.

The actor finally decided to ask Saira for marriage. “‘Saira, you are not the kind of girl I want to drive around with, or be seen around with… I would like to marry you… Will you be my wife?,” he said. “‘…and how many girls have you said this to?’,” was Saira’s prompt reply. She, however, said yes. By Kumar’s own admission, their union had its ups and downs. The initial problems arose from the actor’s huge family of brothers and sisters, who were not very happy to share their brother with Saira.

Kumar also briefly mentions his ill-fated marriage to Asma Rehman in 1982, 16-years after he tied the knot with Saira, calling it the only regret in his life. “Well, the one episode in my life that I would like to forget and which we, Saira, and I, have pushed into eternal oblivion is a grave mistake I made under pressure of getting involved with a lady named Asma Rehman whom I had met at a cricket match in Hyderabad,” he recalls. The actor said Asma initially looked like umpteen other women admirers, who were introduced to him by his sisters. ”In this case, however, I was completely unaware of a connivance that was being mischievously perpetuated and a situation being cleverly created by vested interests to draw a commitment from me… I can never forget or forgive myself for the hurt I caused to Saira and the shattering of the unshakable faith she had in me.” The thespian says during the Asma episode, “it was also wrongly represented that Saira could not bear a child.” “The truth is that Saira had borne a child, a boy (as we came to know later), in 1972. We lost the baby in the eighth month of pregnancy… We took the loss in our stride as the will of God.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dilip Kumar was born as Yusuf Khan in Pakistan. However the actor is very fluent in Marathi, because he had done his schooling in Maharashtra. And Dilip Kumar is well versed with Pune. In an interview with Times of India, Dilip Kumar had said, "In more ways than one, it is Maharashtra that holds the roots of my life and career. I had my schooling at Barnes School in Deolali, Nashik, as a day scholar. Years later, after I became known as actor Dilip Kumar, I revisited Deolali in the course of my search all over Nashik District for an ideal location to film Ganga Jamuna's outdoor scenes."

Dilip Kumar was at the top of his game when he was a part of the industry. And there were, apparently, rumours of a bitter feeling between Dilip Kumar and Raj Kapoor. However speaking to Filmfare, the actor revealed that he was good friends with Raj Kapoor. "Raj and I were like brothers. We were keen football players and I was always welcome at his house in Matunga, like a son of the house. He used to tell me that I should consider acting as a profession. You are so handsome, you can become a star, he’d tell me. I thought it was all right for him to say that because he was the eldest son of the most admired and popular actor of the time, Prithviraj Kapoor. Talent was in his genes. As for me, I didn’t know anything about acting and I was painfully shy chap. As destiny would have it, some years later, it gave us both much happiness to be in the same profession. It did not bother us at all that the media was writing about our so-called rivalry because we knew what we felt for each other and how deeply we cared for each other’s well-being and success."

Dilip Kumar was very popular for the tragic roles in films like Devdas. While he has been lauded for it, the actor actually seemed to have felt very stressed. In an interview with Filmfare, Dilip Kumar said, "I was doing tragedy at a young age. Renowned tragedians like Sir John Gielgud and Sir Laurence Olivier played tragic roles at a later age. They were in their 30s when they achieved glory for their tragic roles. I was in my 20s. It had a telling impact on my personality. Not just Devdas, but roles in other films as well. I tried my best to shed the morbid outlook that was seizing me. I was advised to take help of a drama coach in England who was also a counselor. He advised me to try comedy, which would give me relief and also bring the much needed variety to my acting."

Interesting, that a vital piece of Dilipsaab life came to light, if one was looking forward to get something interesting about Dilip and Madhubala, this was not to be, maybe another day, another time.

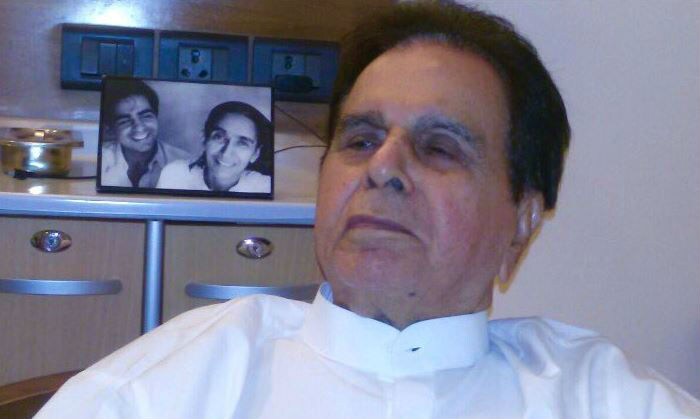

He is an old man now, maybe somewhere in the mid 90's Some say that he was the greatest in his time.....The King of Tragedy:

The Government of India honoured him with the Padma Bhushan award in 1991, the Dadasaheb Phalke Award in 1994 and the Padma Vibhushan in 2015.

asj/file:

DILIP KUMAR AND HIS PADMA VIBHUSHAN AWARD:

Dilip Kumar teary eyed as he receives Padma Vibhushan from Union Home Minister

Dilip Kumar, known as the "tragedy king of Bollywood", turned emotional today (December 13) when he was presented with Padma Vibhushan by Union Home Minister Rajnath Singh.

Dilip Kumar, known as the “tragedy king of Bollywood”, turned emotional today when he was presented with Padma Vibhushan.

Dilip Kumar, known as the “tragedy king of Bollywood”, turned emotional today when he was presented with Padma Vibhushan.

DILIP KUMAR AND HIS PADMA VIBHUSHAN AWARD:

DILIP KUMAR AND SAIRA BANU: RE MEMORIES OF GONEBY YEARS:

Padma Vibhushan For Dilip Kumar, Advani, Amitabh Bachchan and Bill ...

FIFTY YEARS AGO HE WAS 43 AND SHE WAS 22: IT IS WHAT WE CALLED HEAVENLY MARRIAGE IF THERE IS SUCH A WORD

BOLLYWOOD TRAGEDY KING:DILIP KUMAR

Source: Photo: Santosh Nagwekar

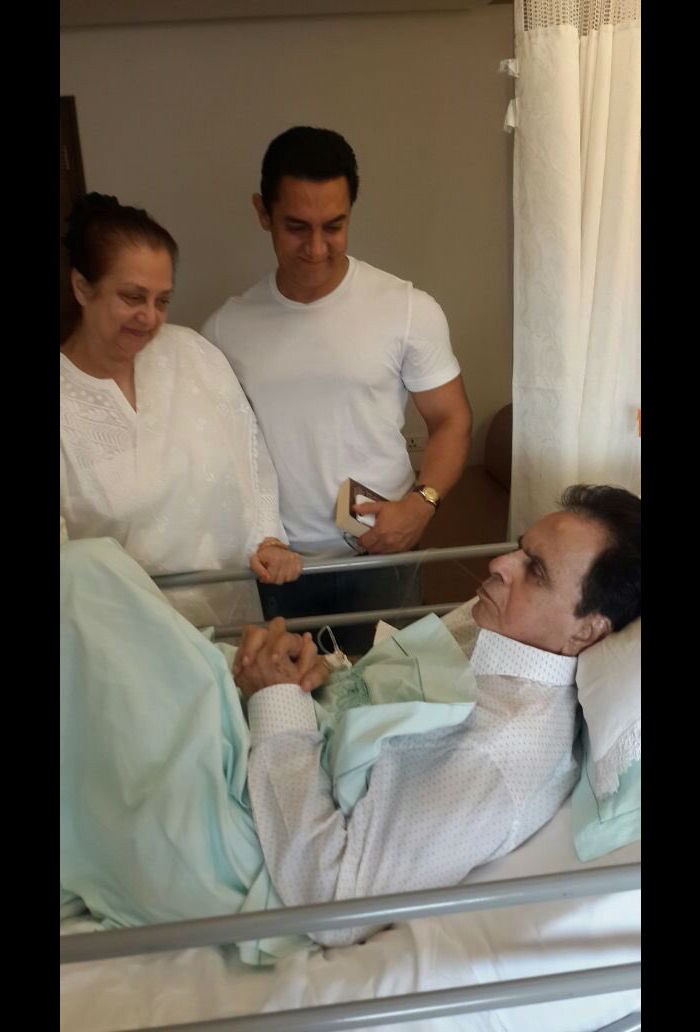

Veteran actor Dilip Kumar was discharged from Mumbai's Lilavati Hospital on April 21. The thespian was hospitalized on April 16 due to chest infection and high fever.

Source: Photo: Santosh Nagwekar

Dilip saab was accompanied by his actress wife Saira Banu.

A TRIBUTE TO DILIPSAAB:

Access to this requires a premium membership.